Christy Lange

What was your first experience with art? I remember my parents had an Eric Fischl coffee table book that I was completely scandalised by. Do you have something like that that you remember from your childhood?

Chris Ofili

I didn’t really have any exposure to art of any significance until I did an art foundation course at Thameside College of Technology when I was seventeen or eighteen. And that was really by accident, because I had wanted to do a furniture design course, and to do that I had to take a course that included sculpture, graphic design, textile design and painting. I really liked painting, so I dropped the furniture idea and just carried on with painting.

Christy Lange

Before that, did you know that you had any proficiency for drawing or painting?

Chris Ofili

No. In design, we had to draw a bit, but it was technical more than intuitive drawing. When I started doing that, I liked that it was completely without boundaries and wasn’t something you did just to get good marks. It was about personal responses. I remember very clearly feeling that this was amazing.

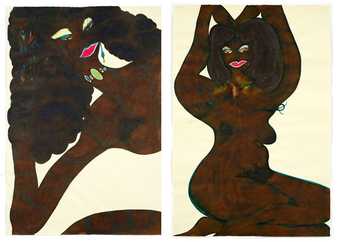

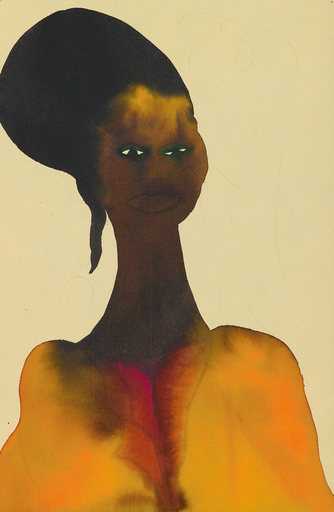

Chris Ofili

Untitled from Afro Nudes 1–4 2007

Watercolour and pencil on paper

63.2 x 43.5 cm

Courtesy Victoria Miro Gallery, collection of Adam Clayton, Dublin © Chris Ofili

Chris Ofili

Untitled from Afro Nudes 1–4 2007

Watercolour and pencil on paper

63.2 x 43.5 cm

Courtesy Victoria Miro Gallery, collection of Adam Clayton, Dublin © Chris Ofili

Christy Lange

So what pushed you to the next level? Did you have a particularly influential teacher?

Chris Ofili

After six months on the foundation course I chose to specialise in painting and drawing. The teacher there, Bill Clarke, introduced me to painting in a way that didn’t make me feel restricted or limited. Not only was it something completely new, but it was something that allowed me to investigate further into who I am. He taught us that it wasn’t so much about painting a scene and making sure you got the shading right, but trying to get to a point where the thing that works is absolutely critical and essential to you as a living, breathing person. I was obviously aware of famous artists, but I suppose I never really thought that was what you could do with your life. He opened the door enough to make me think that it was worth going into the room.

Christy Lange

Do you remember looking at the work of other artists at that time?

Chris Ofili

I remember going to see Late Picasso at Tate Britain (1988), which represented this incredible flood of energy late in his life. I saw how his statements had come one after another in rapid succession, obviously fuelled by ability and immense confidence. I also saw the late paintings of Hans Hofmann shown at Tate (also 1988). His statements were built up over a period of time by making smaller and more arbitrary marks, which then became very definite, coloured rectangles. I remember those two shows clearly, because they both featured the work of painters late in their careers, which can often be an incredible moment or period of enlightenment – or abandonment.

Christy Lange

Your early paintings involved the use of elephant dung, either as part of the work or as its supports, along with a complex, labour intensive system of making patterns of dots and glitter, coated with a thick layer of shiny resin. Your recent work looks much more raw – the dots are gone and there are even exposed bits of raw canvas. Are these new paintings coming out a lot faster because they don’t involve as much intricate patterning and layering?

Chris Ofili

I think they look as though they were done quite quickly because they’re a lot more spare, and the material is not as dense. Whereas the other paintings look like they were made over a long period of time. Of course there’s a certain value attached to that, but it’s kind of a perverse value system. These could take much longer, with a lot less ‘worK’ time and more contemplation and acceptance time. I’m using the material differently now, so I have to think more: okay, what am I going to do now? Where is this going? The minute I make the first move with the brush, I have to make a decision either to refer to the drawings I’ve been working on, or to start having a more direct discussion with what’s in front of me. At first I work with photos or sketches, sort of dancing around it, and after a while, this thing starts to talk back. And that’s when it becomes both scary and exciting. Because this thing starts to make firm demands, and you start to risk losing your original plan.

Christy Lange

This must be a different process of painting for you physically, because you’re not up close to the surface. Do you miss anything about the laborious process you once used? Or do you feel freer working this way?

Chris Ofili

There’s a sense of security in having a known way of working, and I got to a place where I knew that I had control. When you change, all of a sudden you have less control. For me, that change is a really exciting thing, because you can relinquish all the baggage that you’ve built up and just move into a completely new area, travelling light. I think I set things up in a way that I was able to use moving here, to Trinidad, as an excuse – new place, new influences… But really the desire to change was already there.

Christy Lange

Those previous paintings with their combination of glitter and dung seemed to deal with issues of beauty and ugliness, but these newer works appear less overtly concerned with beauty or visual seduction.

Chris Ofili

I let go of that because I think I covered it. I had to let new things in and allow them to take centre stage. Before, the paintings had a kind of grace to them, but the newer ones are quite rugged. That comes out of being here, and actually beginning to appreciate a different aesthetic – going from London life to a life that has a lot to do with nature. I would certainly say that being here has opened my eyes to new and different things.

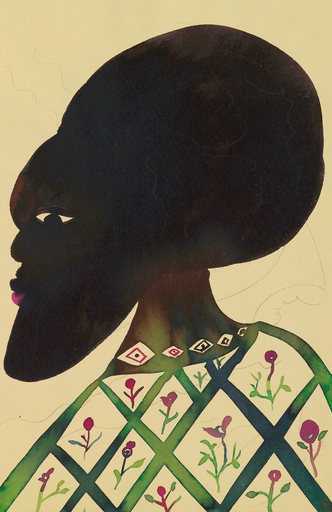

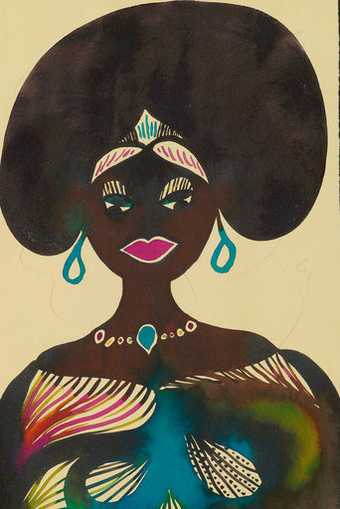

Chris Ofili

Untitled from Afro Muses (Couples) series 1995–2005

Watercolour and pencil on paper

24.3 x 15.7 cm

Courtesy Studio Museum Harlem and Victoria Miro Gallery © Chris Ofili

Chris Ofili

Untitled from Afro Muses (Couples) series 1995–2005

Watercolour and pencil on paper

24.3 x 15.7 cm

Courtesy Studio Museum Harlem and Victoria Miro Gallery © Chris Ofili

Christy Lange

There are a lot of formal references in these new paintings to your immediate surroundings – such as the figure standing in the waterfall in Death and the Roses 2009.

Chris Ofili

For me, the character in this painting is emerging out of a certain kind of darkness. If you go walking through the forest here, you might see a guy dressed in hunter’s attire like this. They are called ‘tall boots’. They’re just Wellington boots with the trousers tucked in. We go to the waterfalls together a lot and the figure in Habio, Green Locks 2009 is loosely based on my friend Mickey standing in the waterfall. In the other half of the painting you see the effects of the water, and then the spray, and then the rainbow effect. There’s also a feeling of attack, or threat.

Christy Lange

I feel the old Chris Ofili would have put a layer of resin on top of this painting.

CHRIS OFILI You see, that’s the thing. This is like a skin of what was before. It’s allowing those things to just sit on their own, to exist in a less refined way. It’s an exercise in how much I can take of myself. How much of “me” do I really want to show? Without a smokescreen. I don’t want to say what I was doing before wasn’t “me”, but in a way you develop and change over time, and you say, okay, I’m ready to take on or present more of myself.

Christy Lange

You moved here in 2005, yet the Afro paintings you made for your 2003 exhibition at the Venice Biennale show lovers in a lush, tropical, Garden of Eden-type setting, which looks a lot like where we are now.

Chris Ofili

I first came here on a residency in 2000, so by the time I made the works for Venice I was already influenced by my experiences here, mixed with ideas of [black nationalist] Marcus Garvey and Africa. But I wasn’t making the work in Trinidad. I was taking the ideas and making it in London. So London was like a remote laboratory, whereas living here now is more like working in the field, or on-site research. I’m not going to say that it’s more authentic, exactly, but the lab is more rudimentary, and the results are going to be less predictable because the environment is harder to control. You’re dealing more with the basic elements and that’s probably what is going on more now in my work.

Christy Lange

Have you lost any of your illusions of this place as one that could represent paradise?

Chris Ofili

I never thought it could represent paradise, or, if it does, it’s paradise as a place where good and evil coexist, side by side. The original paradise, let’s say the Garden of Eden, was always a complicated space. There was ultimate beauty, but then there was the choice to opt out. And I think this place has that going on all the time. There’s always temptation.

Christy Lange

I always thought that the biblical references in your paintings might have been a red herring. Now I’m surprised to hear you talk about spirituality or to describe an element in your painting as a ‘life force’. Has the religious been replaced by something more spiritual?

Chris Ofili

I wonder if the biblical was, for me, always a way to get to the spiritual. When you live somewhere like this, you become aware of different types of energies. The place itself has an undeniable energy. The force of nature is overwhelming.

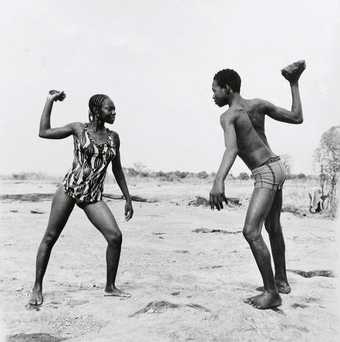

Malick Sidibé

Friends Fighting with Stones 1976

Gelatin silver print

50 x 60 cm

Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York © Malick Sidibé

Christy Lange

Your older paintings used to wear their references on their sleeves, so to speak. Some of them incorporated cut-outs from magazines or album covers, or had artists’ names written on them. They seemed to be much more directly influenced by popular culture. Do you miss any of those things – films, radio stations, magazines, television shows – being here?

Chris Ofili

I think their absence didn’t create a negative space; it created a positive one – if that’s at all scientifically possible. It created a space that allowed for things not to feel as though they’re being destroyed – actually to feel that there were new options available for me. Moving here, it’s like beginning all over again. Before there was always a bigger, more obvious reason on my doorstep for making paintings. Now I have to ask myself: why am I doing it? Why am I trying to make paintings about the tussle between good and evil, innocence and violent intention?

Christy Lange

In 2005 you exhibited ten years’ worth of your watercolours, which were the result of a daily exercise for you. Do you still make watercolours every day?

Chris Ofili

No, I stopped. When I had that show at the Studio Museum in Harlem, that was the end of it, the celebration. I kind of miss it, though, and I would like to replace it with something else. For example, now I keep more sketchbooks, and I make drawings of alternative ideas for images that I’m working on, which allows me to develop images with a more automatic, stream-of-consciousness approach. And I’ve been photographing a lot more here – thousands of photographs a year. I go through them and create folders and files for ideas. I’m seeing so much here, I have to record it because I won’t remember it, and things change so quickly – the light will be different, a tree will have fallen. The leaf that was significant because it was a bluish-green, might be a brownish-green the next time you go back.

Christy Lange

I’m interested in the characters in your work. Though you often title your paintings to suggest that they might be biblical characters, formally the figures may actually be based on a photograph by Malick Sidibé, or a Playboy centrefold. Are they figments of your imagination, or part of a larger story – a long narrative you have going in your head?

Chris Ofili

I don’t think I take that much responsibility for the roles of the characters – I’m more the casting agent than the director. I’d much rather make the selection than tell them what to do once they get on stage.

Christy Lange

You seem to have a really fertile imagination, which comes across especially in an earlier painting such as Captain Shit 1998, who appears to be a kind of superhero alter ego. Did you read comic books as a kid?

Chris Ofili

No, my brother read comic books though. He had a lot of Marvel and DC Comics. A lot of them. Until my mum threw them out. But that’s another story, which he still remembers.

Christy Lange

Did she throw them out accidentally?

Chris Ofili

No. They were taking up too much space. He came home down the street one day and the kids from the neighbourhood were pulling all these comics out of a big skip. And he thought: ‘Wow, this is incredible – I’ve got doubles now! I’ve got doubles for Spider-Man #1!’ And then he saw the red suitcase that he used to keep them in. But I didn’t read comic books myself. I remember I’d always be more interested in reading about the characters’ special powers, rather than what they did when they were out on their exploits.

Christy Lange

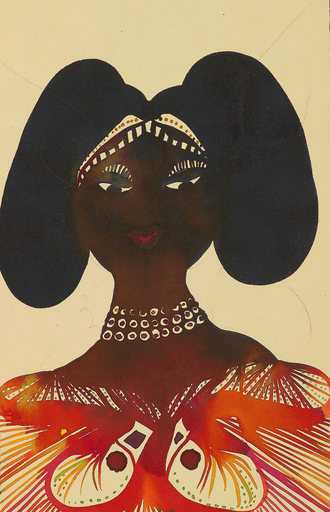

So you weren’t a fanciful kid? Because I do think there is a fanciful streak in your work. You’ve said that each of the women in your series of watercolours, Afro Muses, for instance, is completely imaginary.

Chris Ofili

The Afro Muses are more about process, I’d say. Obviously I can give a glimpse of an individual character by putting the eyes at a certain angle, or placing the nose higher or lower in relation to centre of the page, but really it’s about a formal exercise – the enjoyment of the type of paper, the consistency of the watercolour, the softness of the brush, the way the paint will soak into or flow across the paper, the way shapes could actually shape themselves rather than me having to chisel them out. And being able to sit back and watch things happen, working more in pursuit of that point where the material starts to do things for you, and suddenly, it’s a face, it’s a head and shoulders.

Christy Lange

‘Muse’ is quite a suggestive term, and the relationship between artist and muse is loaded as well, but from what you’re saying, it sounds like none of that is at play?

Chris Ofili

The muse is a form of inspiration for something else. And that’s what they are.

Chris Ofili

I have to ask you about your portrayal of women, because a lot of the women in your paintings – such as Blossom 1997 or Afro Jezebel 2002–3 – seem to be coquettes or temptresses. How much of that is your own characterisation, and how much is it a comment on that kind of characterisation of women in society, or in art history? And if so, what is your take on it?

Chris Ofili

It’s a tricky question, because the answer is probably all of that. It’s probably my portrayal of women in that this is an aspect of women that’s visually interesting for me. And then there are times when it could be a critique of how that has been taken to the extreme in, say, certain types of music. And sometimes it’s just like: ‘I don’t care what it’s supposed to mean or not and what it says about me.’

One day I might say to myself, oh my God, why is this woman painted like that, and then another day I might think, well, that’s a great shape. So I don’t have a stance, really. I don’t need one, either. But the question is food for thought.

Christy Lange

So is it a provocation? Because you have got away with it up to a certain point, while other artists, such as John Currin, take a lot of heat for their portrayal of nude women in their paintings. I’m trying to figure out why you escaped that.

Chris Ofili

I’ve kind of wondered that as well. I think I get away with it – and that’s your term – because I’m not really trying to get away with anything. I’m just doing what I want to do. It’s an inquiry that’s partly based on my own curiosity about the reaction it might provoke, and partly because I’m curious to see what can and can’t work in relation to what should and shouldn’t work. So if it means that I put myself on the line in terms of people’s perceptions, then that’s just a by-product.

Christy Lange

But the other potentially taboo issues you deal with – religion, profanity or black identity – have been investigated in your work, whereas your treatment of women is rarely addressed. Now that I know you, I know that it’s not intentionally exploitative or sexist, but I still don’t know your stance on it.

Chris Ofili

It might be. I just don’t know. In order to see if there’s actually a full match and not just one rally, we’d have to break it down in terms of individual examples. I can’t say I have a general approach as to how I’m going to portray women. I have my position, but I don’t have a formalised position. I wonder if somebody looked back and did a full analysis of the images, whether they might discover that it’s not what I think it is. It may help me; it may accelerate things for me.

Christy Lange

If I look at the Afro Muses, which you finished in 2005, and then at Afro Nudes from 2007, I wonder how you made that leap. How can you go from the Afro Muses, who are very dignified women, and then suddenly throw that out the window and paint very overtly sexual nudes?

Chris Ofili

Because you have to, because of that question. Because, well, I’d like to make some nudes now, and see if I can make beautiful forms. The way the Afro Nudes work on the page is a lot more complex than just making the head and shoulders of the Afro Muses. There are more focal points on a nude than just the eyes, lips, and maybe the earrings and the headdress of the Afro Muses; there are the genitalia and fingernails and the breasts – there’s so much more to try to take care of. I saw that as a challenge, artistically, to try to represent a whole figure. It just so happens that it’s a female nude. But I don’t know if I’ve ever considered whether the image would be more resonant if I treated it otherwise. Maybe as a result of this conversation I’ll try to think about how those elements could be expressed in other ways. Then again, I like women. So I’d much rather paint something that I like and find interesting to look at than something that I think formally or politically will earn me more friends. Because I’m on my own when I make these things.

Christy Lange

How much of a certain ‘ugliness’ in your paintings – whether it be a taboo subject, or actual shit on the work – is a way of diverting the conversation away from something else in the picture? Possibly as a means of escaping from judgment?

Chris Ofili

I don’t think there is any ‘beauty and ugliness’, just different degrees of response to something – different degrees of energy. So you can measure the response to something that’s considered easy to look at – ‘beautiful’ – and something that proves to be difficult to look at – ‘repulsive’ – and maybe the degree of energy is actually the same. I think in some of the paintings I’ve made in the past, I was trying to put the two together in order to measure them up. I wanted to put this ‘repulsive’ thing, a very energetic object – the elephant shit – next to some paint and see if the paint could be as energetic, as powerful.

Christy Lange

Did it feel like a loss when you stopped using elephant dung? Because the use of that form and substance seemed to inspire so much of your work. Gradually you refined that process until, eventually, it was just a prop to hold up the painting, and then it was gone. Did you have to find something to replace that inspiration?

Chris Ofili

I think I put it through its paces, really. The starting point was the elephant dung itself, reacting to it as a form, how it looks, and the associations of it, and then trying to build from there. At one point I thought, well, if I’m going to stick elephant shit on to a painting, I can’t let that be ‘it’ – I have to push the painting so far that somebody would say: ‘Wait a minute, the guy’s got to mean it.’ At the same time, and I think that this will come across in the show, there are lots of other types of inquiries going on within the paintings that don’t necessarily point to the elephant dung. So when I moved away from using it, it was more a hangover about the loss of the relationship to the process, rather than to the material. It was a lovely process, and a lovely way to think about trying to make an image. Very accommodating in some ways.

Christy Lange

Do people overlook the humour in your paintings? I think a painting such as Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy 1997 is actually very funny. There’s always been a streak of black humour in your work that never gets discussed.

Chris Ofili

That is an hilarious painting for me. I mean, can you imagine making that? I had to sit there and look at that and go: ‘I’ve done this. Nobody else is making this up! I made this.’ So I’m looking at it and thinking, this is an unusual one to reckon with. Because it’s really funny to me now, but what happens when I show it outside the studio? Joke’s over, Chris. It’s not funny anymore.

Christy Lange

But you walked into a studio every morning and saw a giant penis that you had painted.

Chris Ofili

Yeah. With a big smile, and big clown eyes and little heads stuck on, with little legs with crotch shots, which made the figures look like crabs, running around. I know. I did it. I’m actually quite looking forward to seeing that painting again in the show. Because I know it’s hilarious. It’s just like: “What?” But it had its ancestors. There’s a painting by Francis Picabia called I Don’t Care 1947, which is like a more abstracted phallus. And I made an earlier drawing called Afrophilia 1997, which has all these different phalluses in it. So Pimpin’ Ain’t Easy was almost like: ‘Okay, I’m going to make the painting of the big phallus. There it is. Let’s see what happens.’

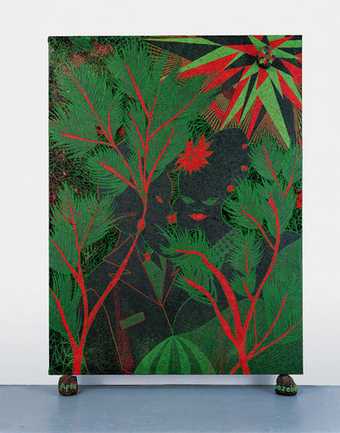

Chris Ofili

Afro Jezebel 2002–3

Oil, polyester, resin, glitter, map pins and elephant dung on linen

243.8 x 182.8 cm

Courtesy Victoria Miro Gallery. Collection of Helen and Ken Rowe © Chris Ofili

Christy Lange

Do you usually discuss your work with other people as you’re making it, or before you exhibit it?

Chris Ofili

I don’t talk about my work that much as a rule. In some ways, I just don’t know what to say. In other ways, I get energy from internalising it, from consuming the frustrations and feelings of revelation. I like to kind of cannibalise on it and see how long I can keep my mouth shut about what I’m doing. Hopefully that will enhance the process. I don’t necessarily think talking about every twist and turn and decision helps me. I just shut up and get on with it and see what I come up with.

Christy Lange

In planning your show at Tate Britain, does it feel strange to look back on everything you’ve done up to this point? Could it be that the audience is ready to look back on your work, but you don’t necessarily feel that you have to?

Chris Ofili

I’m looking forward to the show, but I don’t quite know what I’m looking for. I accept that after doing something, anything, for twenty years, you can have an assessment of it – I think that’s totally legitimate. But whether or not I need to be part of that process, I’m not entirely sure. That’s the one thing that makes me really inhale and exhale deeply.

Christy Lange

Do you feel a sense of anticipation about the reception of your new work in that context?

Chris Ofili

I don’t know if the reception really matters. Because the work is done. And I know, in time, the work doesn’t change; it’s the receptions and opinions that change, and they can vary from one decade, one year, one hour to another. I’m curious how people will respond to the newer work, because they’ll be seeing it far from the environment in which it was made.

Chris Ofili

Untitled from Afro Muses 1995–2005

Watercolour and pencil on paper

24.3 x 15.7 cm

Courtesy Studio Museum Harlem and Victoria Miro Gallery © Chris Ofili

Chris Ofili

Untitled from Afro Muses 1995–2005

Watercolour and pencil on paper

24.3 x 15.7 cm

Courtesy Studio Museum Harlem and Victoria Miro Gallery © Chris Ofili

Christy Lange

You don’t show as often as you probably could, and I wonder how much of that is you just letting the work gestate…

Chris Ofili

I like exhibiting, and I like not exhibiting. I would be very uncomfortable if I always made things to show. I like being here; I like the process of coming to the studio, seeing what happens when something fails or when something opens up a new possibility that can’t be solved in one painting. I like the laboratorial nature of the studio, rather than the factory nature, where it can be more about the processes and experimentation than the end product. I’m interested in trying to make things that can allow me to be more me, if that’s possible. I want to be in a situation where I don’t have to filter out any of myself, and I don’t have to be in a particular mood or in a particular mode. I like what I do to allow me to be totally casual or totally focused, or very serious, throwaway, studious, responsible, irresponsible. I want it to be open to all of that.

Christy Lange

When you say you’d like your paintings to be ‘more me’, do you mean you want your characteristics to come across in your process, or that you want the paintings to be more revealing of your biography? Your newer works are painted in a more expressionistic style, yet they don’t necessarily tell me more about you.

Chris Ofili

In you saying that, I recognise myself. But I also think that there are ways of looking at the paintings that might make you feel quite the opposite.

Christy Lange

So we can feel free to interpret them?

Chris Ofili

I think sometimes the paintings might make you feel that you are getting a little bit too much information. For me, I’m not that interested in the autobiographical being very literal. I haven’t found a way that allows me to sit comfortably with that. So I certainly turn one eye away from that, maybe even turn my back on it. I’m more interested in the mystery of autobiography. I think there are stories that can be told, and they’re kind of on the surface, but there’s an undercurrent underneath it that disappears out of sight a lot more. I think that that level of things is what I’m interested in – in how the self can disappear at times, but still be very active.