Lisa Appignanesi on Paula Rego’s The Dance 1988

Skirts swirl. Feet fly from the ground. The moon shines, illumining the stretch of beach. The dance is on, free, joyous. Yet the shadows are dark. So too is the encroaching sea and the rising bluff. And the dominant figure on the left feels heavy, inert, her feet too big, her stockings too thick for the whirling dance. Despite the twirl of her peasant skirts, despite the fact that she’s the biggest, her gestures are as clumsy as a child’s. Somehow she’s fixed, unmoving, time-trapped. Like the child of memory who is always looking in and on at the grown-ups. The nearest ones here are glitteringly urban, sophisticated, clasping each other, too wrapped up in their dancing embrace to notice the large, ungainly figure at their side.

Paula Rego’s The Dance was one of the first paintings Nicholas Serota purchased when he became director of the Tate. Bravo, Serota.

Like so much of Rego’s work, even at its most joyous, The Dance derails. It provokes us to find a narrative, meanings. Everything here may be homely, yet everything is simultaneously mysterious. Despite the smiles on the faces, things aren’t quite right in Rego’s world. The familiar grows strange. We’re made to wonder about these figures, who bear a palpable, yet enigmatic relation to each other. Is the mystery to do with the tension between light and dark, the conflict between movement and stasis, the ruptured expectation: what should be small is big and vice versa? Whose eyes are we meant to look through?

The large figure on the left wears peasant garb and her hair is tidied into a kerchief. Her eyes gaze out on the scene, but shy away from the dancing figures towards the shadow. The couple are oblivious of her. Maybe, despite their tangibility, they only exist in each other’s minds. She seems to be looking inward, to the past and perhaps also to the future. This dance on a Portuguese beach is also a dance of life and through time.

I read somewhere that the peasant figure is meant to represent Portugal. If she does, she’s a very girlish motherland and, like the whole of the painting, already holds all the generations in herself. The man is Rego’s husband, the artist Victor Willing. She asked him what to paint next, and, just before he died, he told her to paint people dancing. But the dead husband also resembles her son, Nicholas. Like a long goodbye danced to the music of memory, Rego gives us the theatre of her inner life. This is what I love about her work: the sense that memory and dream and childhood perceptions are always there, playing in and with the detailed reality of things, setting up surprising relations.

Paul Noble on Richard Dadd’s The Flight out of Egypt 1849–50

Richard Dadd

The Flight out of Egypt

(1849–50)

Tate

Down from the palm tree – that slices in half this caramel sandstorm of a camp in chaos – stands an armoured man, legs astride, slaking his thirst from a round metal bowl. He has four faces, and not one is human. What fearful symmetry. At the heart of the painting and in the middle of this soldier is a lion’s face, the buckle on a jewelled belt – the Lion of Judah, the agent of God the avenger. The armoured man whose human face has been replaced by the shiny metal disc is a lion. Oedipus Rex Richard Dadd, king of the jungle, avenging wrongs and leading us out of slavery. Richard Dadd, you killed your dad. We are all killing animals. Fearful symmetry. Scroll right, in a line from the lion’s face. An old blind man with moustache, beard and hair parted evenly is sitting, with a round metal bowl in his lap. Wearing a scared frown he listens as a young man whispers in his ear. He is Oedipus cast out, and it is the artist’s nightmare.

Richard Dadd’s The Flight out of Egypt was purchased in 1947

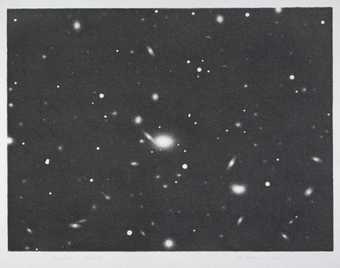

Jennifer Wiseman on Vija Celmins’s Galaxy 1999

Vija Celmins

Untitled Portfolio: Galaxy

(1975)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

As a professional astronomer with more than a passing knowledge of the views of space from the Hubble telescope, my first reaction to Vija Celmins’s rendition of a Hubble image was a sense of unfamiliarity and rediscovery I did not expect. The Hubble Deep Field, represented here in her work, was created by pointing the telescope at a relatively ‘average’ region of space with no known outstanding features. Light was collected from the same small field of view or several days, thereby detecting even the faintest glimmer of distant objects. What emerges in the resulting image is a fantastical array of colourful lights, like fuzzy gems against the backdrop of dark, empty space. When one realises that each dot of light in the image is an entire galaxy of hundreds of billions of stars, the response is always one of astonished humility, whether from a scientist or a casual observer.

What Celmins masterfully achieves is a new perspective on Hubble’s view of the universe, spawning my own reaction of rediscovery. For when the image from the telescope is examined, the usual immediate response is to peer into the details of individual galaxies, noting the beauty of colours and spiral arms and diverse shapes. The scientist will take the focus on detail to even greater depths, asking: ‘How distant is this galaxy?’; ‘Which camera was used for this image?’; ‘What types of stars make up this cluster?’ In contrast, by removing the distractions of colour and detail, Celmins enables us to focus on the view as a whole, discovering a pattern of light on a background sea of darkness. She excels at noticing and re-creating the large-scale patterns of exquisite beauty in nature often overlooked: skyscapes, desert floors and ocean waves. Here, her display of galaxies is reminiscent of the words in Genesis: ‘And God made two great lights, the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also.’ She has captured a new essence of the Hubble Deep Field – a grand pattern representing unfathomable numbers of places as yet unexplored. We are reminded that we are part of something bright, immense and sublime.

Galaxy was purchased in 1999

Neal Brown on Tracey Emin’s Exploration of the Soul 1994

It’s a pretty self-explanatory sentence when you know it comes from a description of the loss of Emin’s virginity at the age of thirteen. It is New Year’s Eve, and what starts off as a snog between Emin and an older male in the doorway of a Burton’s clothes shop in Margate becomes less romantically magical as she is dragged into an alley, clumsily fingered, and then subjected to a grunting sexual intercourse. She describes lying motionless, worrying about her coat, and then crying in pain; justly entitling her to her description of hurt and distress. This short, tombstone sentence is both a plea and an encapsulation. It is not just about trying to resist a selfish, advantage-seeking male, but about the sadness of the world itself, as if she’s somehow saying: ‘Get off please world, you’re too much for me, you’re hurting me.’ The ‘please’ bit of her pleading seems particularly sad – the good manners and reasonableness of it not effective in the mean-spirited circumstances. ‘I’M NOT A VIRGIN,’ she tells her mum later.

The line is from her book Exploration of the Soul, self-published in 1994. It comes in a calico bag with the initials T.E. hand-sewn on the cover, giving it a homely, cheering quality. This is misleading though, as its contents are deeply alarming. There’s also a murdered pet rabbit, a description of Emin’s pride in her mum craftily removing lead from a roof, a bit of incest, as well as some genuine spiritual reflection. She has often used text in her work. Her blankets employ cut-out text; her monotypes are a marriage of autograph text and image; her neon pieces brightly advertise her written sentiments; and her videos and films employ a narrative voiceover. It is literature as well as art, complete with Emin’s eccentric grammar, vocabulary and handwriting, all of which give a unique intonation to her militant storytelling.