Bice Curiger

The first work of yours that I saw was Ghost 1990 – which was the negative impression of the inside of a room, shown at the Chisenhale Gallery. Then in 1992 I co-curated the exhibition Double Take: Collective Memory and Current Art at the Hayward Gallery and we included several of your sculptures. I remember that when I came to London at the time I felt there was a certain hostility towards contemporary art.

Rachel Whiteread

Yes, definitely. It was good though, wasn’t it?

Bice Curiger

Yes, because it brought out a passion to defend it, and I still feel some of that energy in London now.

Rachel Whiteread

It’s interesting that you spotted that back then, because I think that attitude was a result of Thatcher’s Britain. My generation of artists had lived through Labour governments and then an horrendous Conservative government. We were angry and reacting in various ways to the political climate. There were not necessarily things that you would notice in the work, but I think everybody had this, as you say, energy, and everybody was feeding off each other as well. It was hard to put on exhibitions. I’m not saying it is easy now, but there are a lot more available these days. (I think the popularity of art in London now is a little bit overwhelming.)

Bice Curiger

Then a year later, in 1993, you made House – a concrete cast of the inside of an entire Victorian terraced house, which was to become a much talked about artwork that some saw as controversial. It’s hard to understand now why it was so debated…

Rachel Whiteread

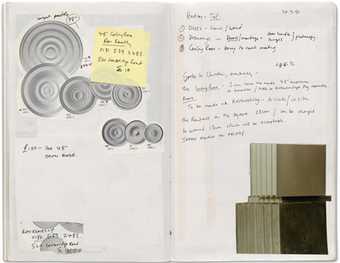

Parts 1–4 of House Study (Grove Road) 1992

Correction fluid, pencil and watercolour on colour photocopy

29.5 x 42 cm

Courtesy the artist and Gagosian, London © Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread

The piece was confrontational. It was in the street, it wasn’t polite, and it wasn’t a memorial. It was this thing that the local authorities claimed had appeared overnight, even though they’d given us permission to make it. People reacted so strongly to it. Although most were positive, there were a few who were very negative about it. There was one person in particular, a councillor, who wanted it knocked down. He tried, from the moment it arrived, to get rid of it. It was an extraordinary time. There was even debate in parliament about it. I knew it was going to be controversial, but I hadn’t anticipated how controversial it would be. And it was hard, because I felt that I hadn’t even really seen the work. There was all this controversy to deal with, and then it was ripped down. I would like to have had a private few weeks with it, with no one telling me what to do, think, or be. So I was really sad about what happened, but ultimately I am very proud of the piece, and actually very proud of the controversy that it stirred. I think it made for a very interesting debate about contemporary art.

Bice Curiger

I’m also sure that the discussion of artwork in public spaces could be, or should be – or perhaps should not be – about monumentality; about the gesture of recollection on a more symbolic level. I think that yours is such an important work for this discussion.

Nigel Shafran

The Site of Rachel Whiteread's House 1994

Colour photograph

© Nigel Shafran

Rachel Whiteread

I think it embodied all of those things. Then, foolishly enough, in a way, I started to work on the Holocaust memorial in the Judenplatz, Vienna. Making that happen was five years of hell. I’m extremely proud of it, but it was a very difficult thing to do. Since then I have shied away from getting involved with projects such as that, because I just don’t need to do them. I want to make my work, I want to make my work seriously, but I don’t want to be involved in political machinations and conflict.

Bice Curiger

But you have made your statement. It’s there, it’s very important, and it has a logic concerning memory, monuments and history. It’s not the grand story anymore; it’s more about things that got lost in the grand story. I think your work is very much about that.

Rachel Whiteread

Completely, but if I’d had any idea of how much controversy there would be, I would’ve thought twice about doing those projects. I’m an emotional sponge and you pay a high price for years of controversy. I’m making a piece in Norway – a cast of a boathouse – which will be on a fjord that is an hour-and-a half outside Oslo, which only very few people will see. I’m really looking forward to this piece. It will have a very different, quiet life, and hopefully it will just sit there peacefully.

Bice Curiger

For your Tate exhibition you are showing more intimate work, both drawings and personal objects that you have collected over the years.

Rachel Whiteread

Stairs 2003

Collage, gouache and pencil on paper

66.5 x 51 cm

Courtesy the artist and Gagosian, London

© Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread

My drawings are very much part of my thinking process. They are not necessarily studies. I use them as a way of worrying through a particular aspect of something that I’m working on. Quite commonly, there will be a dozen or so drawings of more or less the same thing. I find it quite a therapeutic process, and it’s something I’ve done for the past twenty years. I have wanted to do a drawing show for a long time. Whenever I look at a drawing, I always know where I made it and more or less what time of day it was when I made it.

Bice Curiger

So it’s almost a way of writing a diary?

Rachel Whiteread

That’s exactly what it is, and it is actually a very reassuring thing. It’s a nice way of thinking about time passing.

Rachel Whiteread

Untitled (Vienna) 1996

Sketchbook

35.5 x 22 x 2.7 cm

Courtesy the artist © Rachel Whiteread

Bice Curiger

And you are also showing objects…

Rachel Whiteread

There are some sculptures, but very few due to space issues at Tate Britain. There is a vitrine, which will display objects that I collect whenever I go travelling, or from junk shops and off the street. I never really know why I’m collecting these things, and it wasn’t until we started working on the drawing show that it became completely clear what they are. They’re as much drawings, for me, as the drawings themselves, and they’re related to casting and they’re sometimes related to domesticity – they’re a little bit of everything. People get me things, they buy me things, but very few of those have actually gone into the cabinet. I don’t want to sound ungrateful, but it’s definitely my own eye.

Bice Curiger

I think many of those objects have to do with the projection one puts into them. There is also a certain innocence, because you don’t know the story behind them. For example, whether this knife has murdered a person or not, and you might have information that is shocking or deluding…

Rachel Whiteread

Exactly. People often come to my studio and they look at these things. Then when they leave they say: ‘Oh, that really haunted me, and every time I see one of those now I think about your studio.’ It’s quite funny how innocent little objects can be so affecting.

Rachel Whiteread

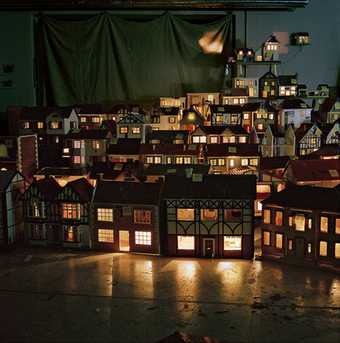

Place (Village) 2006–8

Installation view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 2008–9

Courtesy MADRE Museo d'Arte Donnaregina, Naples © Rachel Whiteread

Bice Curiger

That reminds me of when I saw the photo of your collection of doll’s houses, Place (Village) from 2006–8. It then occurred to me that a lot of what has been written about your previous work is about past lives, death masks, mortuary stones and so on – all death-related connections. Yet the doll’s house is more positive, more life-orientated. If you give your child a doll’s house, it’s for the future, it’s not about past lives.

Rachel Whiteread

I started collecting doll’s houses about 22 years ago, by chance. I bought maybe three or four, and then people started buying them for me. I didn’t really know that to do with them, but I kept buying them, and the more dishevelled and unloved they were, the more I wanted to look after them. They built up on the shelves in my studio – similar to the way I finally made the piece. I didn’t think I was going to light it at first, but eventually it seemed to me that it was best to cast the spaces with light. I had wanted to make something that wasn’t sentimental, but would make children gasp when they saw it. When I first showed it at the Hayward Gallery a few years ago, it was extraordinary to stand there and listen to the noises. People often don’t make a sound when they see art, but there would be an ‘ah’, or an ‘oh’ – it was an emotional reaction, but not, I hope, in any way sentimental.

Bice Curiger

What is your criteria for selecting these objects for your collection?

Rachel Whiteread

Often, when I go somewhere, I’ll try to find the strangest object. There is, for example, a penis ashtray I found in Egypt. What a bizarre object. The material is some sort of cast plastic. It’s rubbish, absolute rubbish. Things like that I don’t necessarily look for, I just find them. I can’t help myself. I have a hand-made funnel that was made to get into a particular part of an engine. It is just a very nice thing. I used to have it in a light when I was a student. Some of these things I have had for years and years. There are all sorts of bits of doll’s house furniture, Japanese teapots and squashed cans, just things that I found in the street. The squashed can I picked up in my first week at Brighton Polytechnic, and I’ve just carried it around with me, not knowing what I was going to do with it. I’ve finally made a print with it. These things have a purpose, although I don’t necessarily know the purpose when I first pick them up.

A selection of items in Rachel Whiteread's studio, including a penis ashtray bought by the artist in Egypt

Bice Curiger

There are some objects here that look like hotel keys…

Rachel Whiteread

Yes, my sons found these in the street and said: ‘Mum, you’ll want these for your collection.’ So, unfortunately, my addiction to strange objects is becoming part of the family. Actually, I have a collection of stick-guns that my eldest son started when he was two or three. He wasn’t allowed a gun, so of course he was obsessed with them, and you would always find these little sticks in his pockets, so I now have them in the studio.

A selection of items collected or made by Rachel Whiteread 2009

Courtesy the artist

Bice Curiger

There is a lot of strange extravagant handicraft.

Rachel Whiteread

There are these children’s toys, which I think came from somewhere in South America and are just very beautiful hand-made objects. Also, I have collected little Vietnamese paper shoes, high-heeled shoes, make-up kits and glasses – they’re wonderful. I have casts for making pills, which belonged to a vet. You’d mush up this paste, and then you’d push it into the casts and wait for it to dry overnight in order to make these great big horse pills. There’s a little cast of my name, which I’ve had since I was ten or eleven years old. These are galoshes that you put over the top of your shoes, which I always had when I was doing a lot of casting in plaster. I was often looking out for weird rubber things that I could fill up when I had too much material. In my studio, I always had bathing caps, hot water bottles, galoshes and enema bags – anything that I could fill up. One of the early pieces that I made on a bronze-casting course was a cast of the inside of a swimming cap. It was technically very difficult to do, as it’s only a couple of millimetres thick. I also cast my own ear in bronze.

Bice Curiger

It looks like it is 200 years old. And how did you get the cast of Peter Sellers’s nose?

Rachel Whiteread

There was a company that I was working with, and in order to show you new materials they’d give you samples in the shape of Peter Sellers’s nose. A lot of these things were material samples, for working out the clarity of a particular type of resin I was using, or polystyrene that I’d pick up off the beach – just things that are connected, colours that I’m thinking about using, or shapes and materials. I have a number of fossils, which I always think are like drawings. There is this dinosaur’s backbone – an incredible thing, actually, that I collected with my dad when I was about six years old. He was a geographer and we found it in Lyme Regis while on a field trip with his university.We also found an enormous ammonite, but that was taken off us to go into a museum.

Cast of Peter Sellers's nose belonging to Rachel Whiteread

Bice Curiger

Did your father’s role as a geographer and the trips you went on influence the way you thought about objects, shapes and landscapes?

Rachel Whiteread

Well, my dad was a geographer and my mum was an artist. Often when we were out as a family driving around she’d suddenly say ‘stop’, and she’d get out of the car and take some photographs. I do exactly the same thing and have done for years. They helped me to look, yes, and helped me to understand the environment and relate to it. It was always interesting, looking at nature, looking at man’s effect on nature, and indeed at man’s negative effect on nature. It was something that I grew up with.

Bice Curiger

How do you decide to group the objects, and how do you order them?

Rachel Whiteread

In the studio, there is no real logic to it. For the exhibition, I started thinking about hands and feet, and then scale and how things would fit together in relation to scale. The exhibition will have been in different places – Los Angeles, Dallas and now London – so it is different in each space. It’s really about how I feel at the time. At Tate Britain I’m sneaking in a few objects that I wasn’t allowed to include elsewhere.

Bice Curiger

As well as the objects, you had also been collecting postcards…

Rachel Whiteread

The postcards are part of the same process of picking things up when I’m travelling. Some of the earliest ones I found in Berlin. When I first lived there you could buy these great postcards, which I’m sure you can’t find anymore, from all the old museums in East Berlin. They have a beautiful quality. Others are from Russia, from way back in the 1970s. The printing on some of these you just don’t get today.

Bice Curiger

Yes, it is like velvet. I think it’s a technique that is very poisonous and they can’t do it anymore because of the chemicals that go into the water. They were a very important way to create a message, and they were important for artists and creative professionals to work with.

Rachel Whiteread

Explorers took photographers with them, and would make postcards [from their pictures]. Postcards were a way in which people first saw the world. However, I do not want to be nostalgic…

Rachel Whiteread

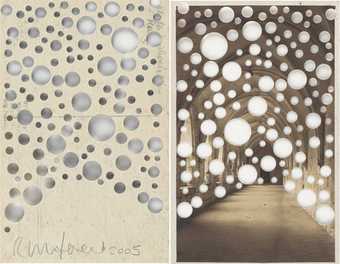

Untitled (Verso and Recto) 2005

Postcard with punctured holes

14 x 9 cm

Courtesy the artist and Gagosian, London © Rachel Whiteread

Bice Curiger

If you go to junkyards or flea markets in London or Berlin, I think there’s an element of projection and history. In Berlin I feel that the past is so present, along with our fantasies about it.

Rachel Whiteread

I think that’s actually changed in Berlin somewhat, but when I was living there I was obsessed with trying to find traces [of the past]. Sometimes you see it around London. For example, look at the side of Tate Britain and you will find that it is completely covered in shrapnel marks. I have always been interested in layers of history, and I enjoy just playing with these layers.