Looking at the history of emptiness in modern art I am often reminded of Zeno’s paradox of Achilles and the tortoise. Zeno imagined a race, in which Achilles would generously grant the tortoise a head start of say 100 metres, and each would move at a steady, unchanging speed. His conclusion was that Achilles would never be able to catch up with the tortoise, because every time he came close, the tortoise would have had time to move a little further, so that the distance between them would endlessly decrease to a few yards, a few metres, one metre, 0.1 metre, 0.01 metre, etc. In the same way, every time the audience of modern and contemporary art is led to believe that the avant-garde reduction of the artwork to a minimal, barely perceptible form can go no further, along comes another artist who creates another even more minimal, even less perceptible, artwork.

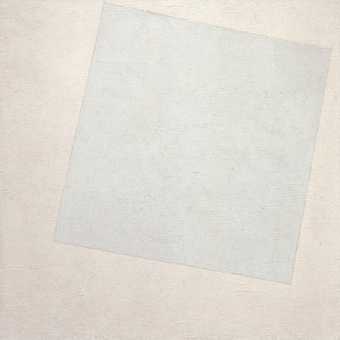

Kazimir Malevich

Suprematist Composition: White on White 1918

Oil on canvas

79.4 x 7 9.4 cm

Courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York/SCALA Archives

Thus, it seemed that the history of modern art had reached its zero point when Marcel Duchamp presented a glass pharmacy phial filled with Paris air to an American collector in 1919, or when Kazimir Malevich painted his White on White composition in 1918, and two years later filled a room with, as one person noted, empty canvases ‘devoid of colour, form and texture’ on the occasion of his first solo exhibition in Moscow. Yet in a 1968 article, critics Lucy Lippard and John Chandler could only observe that ‘the artist… has continued to make something of “nought” 50 years after Malevich’s White on White seemed to have defined nought for once and for all. We still do not know how much less ‘nothing’ can be.’ Thirty-five years later, Gabriel Orozco’s sole contribution to the Aperto exhibition at the 1993 Venice Biennale consisted of an empty shoe box, eight years before Martin Creed notoriously won the Turner Prize partly for his installation Work No. 227: The lights going on and off at regular intervals. Nearly ten noughty years down the line, and shortly after a museum survey entitled Voids: a Retrospective presented visitors with nine perfectly empty rooms, we are still none the wiser about ‘how much less “nothing” can be’.

Ceal Floyer

Auto Focus 2002

Light projection with Leica Pradovit P-150 projector and Unicol telescopic tilting stand

Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery © Ceal Floyer

Year after year, decade after decade, however, one thing doesn’t seem to change: if we haven’t walked through, on, or past the artwork without noticing it, our reactions to this kind of barely perceptible, almost nothing, practice will predictably range from puzzlement and laughter to anger and indignation. Even before Malevich’s 1920 exhibition, a French cartoonist had imagined in 1912 that the empty canvas would be the next avant-garde prank visited on its baffled public. In the caption, the artist presenting his blank canvas explains in a pun on the then-current Futurist movement: ‘It’s the most futurist picture of all – so far it is only signed, and I’ll never paint it.’ As the emptiness and reduction of blank canvases, of white or black monochromes and of Duchampian readymades were extended to silent concerts and empty galleries in the second half of the twentieth century, the question remained: are all these forms of emptiness so many variations on the same provocative joke?

The first documented entirely empty exhibition, Yves Klein’s The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State Into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility – better known as The Void – at the Galerie Iris Clert in Paris in 1958, certainly had all the trappings of an elaborate PR stunt. Not only did Klein empty the exhibition space and paint the remaining walls and cases white, he also posted two Republican Guards in full uniform at the entrance of the gallery, served blue cocktails especially ordered from the famous brasserie La Coupole and had even planned to light up the obelisk on the Place de la Concorde with his brand of International Klein Blue. While the last event was cancelled at the last minute, an estimated 3,000 visitors did show up on the night of the opening, filling the streets around the gallery as they waited to enter the exhibition space through blue curtains, one small group at a time. The crowd was finally dispersed by the police called in by disgruntled visitors who had felt swindled after paying their entrance fee to be shown an empty gallery. In some ways, the succès à scandale of The Void has obscured Klein’s very idiosyncratic brand of showmanship and mysticism. His interest in the immaterial was genuine, inspired by his exploration of monochrome painting and his belief, influenced by Rosicrucianism, that humans must strive to liberate themselves from flesh and matter.

If some artists since Klein have embraced such spiritual readings of the void, a more general preoccupation with the invisible seems to account for many empty exhibitions in the past 50 years or so. Maria Eichhorn, a German artist whose early work includes white texts written on white walls, speaks for many artists when she explains: “There is such a fixation in our Western culture on the visible, which explains why we think that… a room is empty… because there is nothing visible. But I’ve never thought that an empty room is empty.” In the late 1960s Robert Barry had already pointed to the imperceptible forces that literally surround us by introducing radio waves as well as magnetic currents into the gallery space. American artist Maria Nordman has tried to focus viewers’ attention on the light falling through an empty gallery’s windows at different moments of the day and of the year. More prosaically, other artists have invited visitors simply to contemplate the architecture of the gallery. Arriving in 1993 at the Museum Haus Esters in Krefeld, originally a house designed by Mies van der Rohe, British artist Bethan Huws felt she could not add anything to the beauty of the modernist building. Instead, she distributed a poem to visitors and let them admire the gallery for itself.

In the 1970s American artist Michael Asher pioneered strategies through which to reveal the architectural structure of the gallery. At the Clare Copley Gallery in 1975, for example, he simply removed the wall separating the empty exhibition space from the art dealer’s office. By opening up this space, the artist was not only inviting visitors to consider its architectural features: he also reminded them of the Business transactions taking place behind the walls of commercial galleries. After Asher, other artists have explored the invisible networks of art business and institutional presentations that frame the art we view. Maria Eichhorn used the budget allocated to her show at the Kunsthalle Bern to tackle the institution’s debts and fund much-needed refurbishments of the building (Money at the Kunsthalle Bern 2001), while in their 2005 Supershow – More than a Show, the collective Superflex used theirs to give each visitor two Swiss Francs instead of asking them to pay an entrance fee to see empty spaces adorned only by texts stating the physical properties of each room (surface, wall colour, maximum number of visitors, etc). Museum surveillance is alluded to in Roman Ondák’s 2006 More Silent than Ever, which warns visitors that hidden listening devices are installed in the room.

Installation view of Roman Ondák’s More Silent Than Ever 2006 at GB Agency, Paris

Courtesy GB Agency © Roman Ondák

Presented with invisible elements such as Ondák’s listening devices or Barry’s magnetic fields, we are left wondering whether to believe the artists’ claims since, after all, there is no adequate way to confirm them. We come to realise that our relation to the work is predicated on knowledge, presuppositions and some form of trust in the authority of artists and art institutions. British artist Ceal Floyer traces her interest in minimal displays back to her experience as a gallery invigilator while she was an art student. ‘I watched a lot of art being seen. And a lot of art being not seen,’ she remembers. ‘That was a training in itself. I discovered that presumption is a medium in its own right.’ As with Creed’s The lights going on and off , Floyer’s plastic buckets and black rubbish bags casually sitting in the gallery certainly reveal to us our prejudices and expectations as to what art is or should be. Gabriel Orozco says he actively seeks to disappoint his viewers. Is my irritation at being presented with an empty shoe box or lights going and off ultimately good for me?

Installation view of Ceal Floyer's Garbage Bag at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham 2001

Courtesy Kunsthalle Bern © Ceal Floyer

Ceal Floyer

Ladder (minus 2–8) 2010

Aluminium ladder

Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery © Ceal Floyer

The veiled hostility directed by the artist at the viewer situates such attitudes in the context of more radical declarations against art and its institutions. When presenting her empty exhibition at the Lorence-Monk Gallery in New York in 1990, American artist Laurie Parsons went so far as to refuse to include her name on the invitation to the opening and to remove all reference to the show from her CV. Four years later, she ceased to produce works altogether, thus following a line of artists before her who deliberately decided, as part of their practice, to give up, or take a break from, the profession. From this perspective, the empty gallery is less an artwork than a gesture – of provocation, dissent and critique. As Brian O’Doherty has shown in his well-known study of the modern “white cube” gallery, such a gesture ‘depends for its effect on the context of ideas it changes and joins’. For the gesture to succeed, its timing, place and audience have to be just right. Sometimes it can be understood only retrospectively, as it becomes historicised.

Installation view of Laurie Parsons's 578 Broadway, 11th Floor 1990 at Lorence-Monk Gallery, New York

Courtesy Lorence-Monk Gallery © Laurie Parsons

It would be unfair, however, to reduce all explorations of emptiness, nothingness and the invisible to the rhetoric of the gesture. To return to Orozco’s Empty Shoe Box: when it was first shown in 1993, it certainly poked fun at the Venice Biennale’s frenzy of publicity and consumption, but it also served as a memorable image of the container or vessel that is a leitmotif in the artist’s work. ‘I am interested in the idea of making myself – as an artist and an individual – above all a receptacle,’ stated Orozco. Playing with contrasts between empty and full, his work as a whole exemplifies a sensitivity to reciprocal spatial relations. In a notebook, he compares discarded pieces of chewing gum on a pavement with the stones placed on a board in the Asian strategy game of Go. Like Empty Shoe Box, the Go stones and the spat-out blobs of gum occupy and cut out space, demarcating a territory according to very specific patterns of chance and intention.

Gabriel Orozco

Empty Shoe Box 1993

Shoe box

40.6 x 50.8cm

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © Gabriel Orozco

Many artists have similarly been interested in the space between objects. Both the Belgian Joëlle Tuerlinckx and the Brazilian Fernanda Gomes often present arrangements of small, discrete everyday objects scattered around otherwise vacant gallery spaces. Tuerlinckx describes the exhibition space as ‘a kind of parcel, a packet of air’ that she is invited to open and explore through her work; Gomes says she never comes to the gallery with a pre-defined plan. In these installations, the empty gallery becomes a blank page to be inscribed (as in Tuerlinckx’s spatial drawings), or the pregnant void that surrounds objects in paintings such as Giorgio Morandi’s (in Gomes’s three-dimensional still-lifes).

Painting is also a surprising reference for the performances staged by Marie Cool/Fabio Balducci, during which Cool stands in an empty room as she enacts a series of repetitive, extremely precise gestures using flimsy everyday materials such as paper, tape, or thread. The French- Italian duo has claimed that the image of a figure hovering in an undefined yet meaningful space was inspired by early Renaissance religious painting such as Simone Martini’s Annunciations. The empty gallery as a stage for action has also been effectively used by Martin Creed, when he asked runners to sprint down the Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain, one by one at regular intervals, in 2008, or by British-German artist Tino Sehgal, who in 2010 choreographed two continuous scenarios, involving three actors, in the spiral rotunda at the New York Guggenheim Museum.

Installation view of Turner Prize winner Susan Philipsz's Lowlands at Tate Britain October 2010

© Susan Philipsz . Photo: Tate Photography

Placed in vast expanses of void, both bodies and objects appear more vulnerable. On the one hand, such installations provide an alternative to the spectacular displays encouraged by increasingly large-scale museum and gallery spaces. By celebrating the commonplace, the barely noticed, as well as frailty and precariousness, artists thus seem to be actively resisting the pressure to create ever-bigger, glossier, more awe-inspiring works. On the other hand, however, such minimal mises en scène can create new forms of spectacle – as when Maurizio Cattelan places his miniature self-portrait, a resin figurine hanging from a clothing rack, in a corner of the empty gallery in order to emphasise his apparent failure to take on the revolutionary role of 1970s artists such as Joseph Beuys (to make the point, the Cattelan mini-me is clad in Beuys’s signature felt suit).

While such formal devices are often little more than simple gimmicks, works that effectively stage their own weakness and vulnerability can raise questions about the institutional and social conditions that guarantee their existence as art. In Hans Christian Andersen’s tale of The Emperor’s New Clothes, a naked emperor is persuaded by his tailors that his fine clothes are visible only to intelligent people; his subjects, afraid like him to admit that they cannot see them, applaud his outfit until a small child in the crowd finally blurts out the truth – ‘But he’s got nothing on!’ Though above all a cautionary tale against the deceptive powers of flattery, vanity and sycophantism, the story also provides an image of the willing suspension of disbelief required by most forms of art. After all, the artist’s deception, like the cheating tailors’, could never work without our participation. In his 2002 work Lament of the Images, Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar mobilises this kind of community of believers by presenting us with two dark, apparently empty rooms. In the first, we come across three small backlit text panels relating real stories about invisible or impossible images, such as the fact that the United States Defence Department purchased the rights to all available satellite images of Afghanistan during the 2001 air strikes so that the global media could not publish them. The second room houses a single, brightly lit, empty screen. Blinded by its light, we are reminded of our own blind spots – our complicity in the invisibility of certain images and in the existence of many an emperor’s new clothes.