One of the first artists to merge the realms of performance and installation, Marc Camille Chaimowicz over the past 40 years has deftly combined sculpture, painting, drawing and photography with elements from the decorative arts. His work positions objects and images to give a poetic energy to personal and otherwise quite ordinary-seeming moments. He does this through a highly staged sense of tableaux, of creating a scene that does not draw a distinction between working process, finished object and the barely observable rituals of everyday life. The way he has fused elements of performance and installation alongside a dandyish attention to subject has been influential on younger artists. For the first time at Tate Britain, a performance work, Chaimowicz’s Partial Eclipse 1980–2006, will be integrated within the displays.

The piece will be shown as a performance about to happen. This sense of potential – both charged and arrested – may explain why the practice has become a major, if often hidden, aspect of contemporary art. Arrangements of objects reflect the acts and procedures that the artist has followed, as well as referring to other kinds of events and histories. Corin Sworn’s installation Endless Renovation 2010, for example, explores issues connected with the way in which memory always leads to a history that is constructed. It is to be shown as part of the Art Now series of projects by emerging artists.

In his installations, Cerith Wyn Evans questions and reconfigures the certainties of language and other conveyors of meaning – including Morse code. Frequently incorporating found or remembered texts from film, philosophy or literature, his work’s elegant and apparent simplicity explores the notion of language as a code or convention that can be acted out in a number of different ways. His Has the Film Already Started? 2000, for instance, suggests the language surrounding presentation or projection can be a provocation to an audience, but that the reaction of an audience is also a major part of any work.

Both Mike Nelson’s The Coral Reef 2000, his first large-scale labyrinthine work, and Cathy Wilkes’s installation (We Are) Pro Choice 2008, also a new acquisition by Tate, demonstrate how artists construct environmental tableaux in different ways. Nelson and Wilkes explore a distinctly personal vocabulary of domestic objects and materials that appear in ever-evolving assemblages and environments. As Nelson explains in respect to The Coral Reef: “I look for a particular type of object or thing to articulate different types of space. Certain objects and materials have a power or imbued knowingness to their own history. One object like that can articulate a whole space.”

Like Wilkes, Enrico David creates his own visual vocabulary from pre-existing material, assimilating folk art, twentieth-century design and pornography into his evolving personal archive of forms. The body in his work is in a constant process of reconfiguration and deconstruction, offering a surrogate of sorts for the artist’s subjectivity. Similarly, the female protagonists in Bonnie Camplin’s films, often played by the artist, inhabit a sequence of “looks”, resembling a form of female drag. They share a combination of assertiveness and vulnerability, at times exposed and at others heavily disguised.

Archive material has also proved to be a useful source for investigating the relationship between the document and performance. Yet this relationship is not quite as clear-cut as it may at first seem. Stuart Brisley, for instance, often sees his performance as material out of which work might be made – predominantly as carefully edited and presented photographic sequences, or as film. For artists such as Genesis P-Orridge and Cosey Fanni Tutti, whose art is produced in the spaces between different artforms – under the term Intermedia – there can be no hierarchy of form. Photographs and objects take on another charge quite distinct from that provided by the original experience of witnessing an event. For them, performance continues to be “concerned with experience – direct, first-hand, individual interpretation of action. It uses as its base the imaginative interpretation of life itself, the raw material being drawn from the everyday”.

Andrew Wilson on Bruce McLean’s Nice Style

When Bruce McLean (along with Paul Richards, Ron Carr, Garry Chitty and Robin Fletcher) founded Nice Style, what they called the “World’s First Pose Band”, in 1971, and performed in May as support for The Kinks at Maidstone College of Art, the onlookers must have been bewildered. The pose of pop music was stripped down to just a “correct” or “nice” pose – with no sound. And what was style? The previous year, in a review of the ICA’s survey exhibition ‘British Sculpture out of the Sixties’, McLean had skewered the arbitrary and dogmatically held aesthetic judgments that had driven the success of Anthony Caro and the New Generation sculptors (including Phillip King and William Tucker), who had until recently occupied the vanguard of contemporary sculpture in Britain, typified by coloured abstract sculpture made from welded steel or the new (for sculpture) material of fibreglass.

Style was identified by McLean as he put it in the title of his review, “Not even crimble crumble”, describing it as “a sort of ease, a style that some people have, cultivate a bit because they know when they’ve got it, work on it; it has to do with ‘craft’ tricks, then perpetuating the tricks, never letting them become completely boring”.

Satire, parody and caricature were not new strategies for McLean: the year before, in April 1969, he had presented his Interview Sculpture at the Royal College of Art. For this, his St Martin’s contemporaries the “Living Sculptures” Gilbert & George asked him questions about a number of sculptors (including King, Caro, Tucker and David Annesley), which he answered by mimicking or parodying their work, a little bit like a game of charades in reverse. This sculpture was the first that he had performed in front of an audience, and marked a turning point for him.

Re-presented later at St Martin’s and at the Hanover Grand under the changed title of Impresarios of the Art World, the work made clear his intent to scrutinise and dissect the pretensions and stylistic conventions adopted by an art establishment. The review “Not even crimble crumble” was accompanied by his photowork People Who Make Art in Glass Houses 1969, which in a similar way to Interview Sculpture satirises the achievement of New Generation sculpture: McLean stands in a small greenhouse, with broken glass and no roof, holding elements of a New Generation-type sculpture, effectively throwing a stone at the tradition that formed him as a student.

By 1969 McLean had himself moved from creating pieces made out of everyday materials, fabricated or just found in the street, to using his own body as the source of his sculpture. If his earlier works had addressed the ways in which sculpture had changed – predominantly under the influence of Caro – in terms of material, form and context, then his discovery of “pose” continued his critical challenge towards what might make a sculpture and what this might mean.

Pose Work for Plinths 1971 is a series of photographs showing McLean adopting different reclining positions on three plinths, each of a different size. It is a work that deflates the ubiquity of Henry Moore’s sculptures of a reclining female figure – the balance of pose is made awkward by the plinths, and the perceived pomposity of Moore’s monumental civic figures pricked. However, Nice Style’s greatest achievement was also to be its last (the pose work High Up On A Baroque Palazzo), the band breaking up shortly afterwards. Nice Style had quickly moved its attention away from the style of art to the styles of life found within expressions of social hierarchy.

- Pose Work for Plinths I & III will be on display at Tate Britain

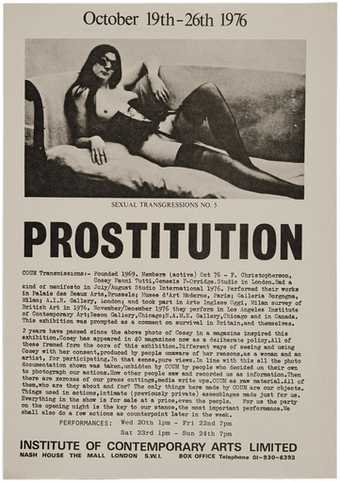

Handbill for COUM Transmissions’ ‘Prostitution’ exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, October 1976

Courtesy Tate Archive

Lizzie Carey-Thomas on COUM Transmissions

“Public money is being wasted here to destroy the morality of society. These people are the wreckers of civilisation,” wrote Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn in the Daily Mail on 19 October 1976. The subject of his tirade was the performance-art group COUM Transmissions and its recently opened, now infamous exhibition ‘Prostitution’ at the ICA, London. COUM Transmissions, founded in Hull in 1969 by Genesis P-Orridge, began life as a series of improvised music events and happenings. At the end of that year P-Orridge met Cosey Fanni Tutti and she joined the group; under their joint direction (and later with the collaboration of Peter Christopherson) COUM gained noteriety throughout the 1970s for its taboo-breaking direct ‘actions’. Its members’ antagonistic approachoften brought them into conflict with the law, the most well-documented of which was P-Orridge’s indecent postcard trial of April 1976. Hijacking the trial as an art event under the title ‘G.P.O v. G-P.O’, complete with invitation cards, he subsequently announced: “What E [sic] am interested in now is that point where Art meets Life and fuses, dispersing art and enhancing life.”

While ‘Prostitution’ ran for only eight days at the ICA, it received a hostile and widespread reaction from the national press, who saw its contents as a deliberate assault on the moral and artistic values of the time. Alongside photographs of COUM performances and related press cuttings (including those levelled at the show), the exhibition included used tampons sculptures, props from past “actions” and framed pages of pornographic magazines from Tutti’s modelling career, available upon request.

Nineteen seventy-six had been a difficult year for contemporary art in Britain, which found itself facing an increasingly sceptical press during a period of all-time economic lows. Since the furore over Tate’s purchase of Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (the “Tate Bricks”) in February, public subsidy of the arts had been forensically examined, and some critics were quick to see ‘Prostitution’ as further evidence of waning standards and a threat to societal values. In a typically agile move, the show was to be both the culmination and death of COUM’s art-related activities – the duo relaunched themselves at the opening as industrial band Throbbing Gristle, abandoning the art establishment altogether.

- Archive material on COUM Transmissions and ‘Prostitution’ has been selected from the Genesis P-Orridge archive held at Tate and the collection of Cosey Fanni Tutti.

Marc Camille Chaimowicz

Detail of Partial Eclipse 1980–2006

Mixed media installation

Courtesy Cabinet Gallery, London © Marc Camille Chaimowicz

Cerith Wyn Evans on Marc Camille Chaimowicz

How do you spell insouciance?

It is with fond remembrance that I first – in astonishment – encountered the “Performance Issue” of Studio International that bore an image of Marc Camille Chaimowicz on the cover. It made my mind alive… and I’ve never really recovered.

I eventually saw several reincarnations of his Celebration? Real Life 1972, and it has haunted me ever since. Marc has said: “It’s more to do with that part of one’s subjective self that maintains a sense of delight in the incidental.” And: “The very concept of a studio was anathema to a number of us then, and so the streets, and notably the streets at night, were material for the need to contest the dominant cultural value of the time.”

He continues to adopt and maintain this radical stance, this melancholy imaginary, this mediated detachment evoking an attitude assumed… reverie.

Again: “The piece wasn’t evidently about real life. It was a fiction; many of the constituent parts were of the everyday, but they were almost [my italics] metaphorical. I guess the question mark [Celebration?] was a metaphor for that gap between art and life.”

How are we to name, to describe, such as I see it from my place, that lived by another which yet for me is not nothing, since I believe in the other – and that which furthermore concerns me myself, since it is there as another’s view upon me? Here is the well-known countenance, this smile, these modulations of voice, whose style is as familiar to me as myself. Perhaps in many moments of my life the other is for me reduced to this spectacle, which can be a charm. But should the voice alter, should the unwanted appear in the score of the dialogue, or, on the contrary, should a response respond too well to what I thought without having really said it – and suddenly there breaks forth the evidence that out there also, minute by minute, life is being lived: somewhere behind those eyes, behind those gestures, or rather before them, or again about them, coming from I know not what double ground of space, another private world shows through, through the fabric of my own, and for a moment I live in it…

Marc has occasioned many things for and in me.