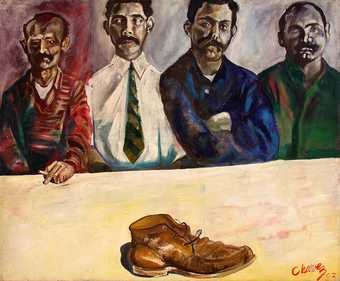

Roberto Chavez

The Group Shoe 1962

Oil on canvas

127 x 152.4 cm

© Roberto Chavez. Photo: Brandon James, courtesy Anatol Chavez

Los Angeles is often called the City of Dreams. It is a place that includes its own dream factory (Hollywood), consumer mecca (Rodeo Drive) and make-believe world (Disneyland), not to mention a subtropical Mediterranean climate, beaches, wetlands and mountains. Ironically, one of the first artworks to capture the failure of this dream for the city’s Mexican-descent population does so by way of a dream deferred elsewhere and for another racial minority group.

On 4 September 1957 nine black students attempted to enter Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, only to be turned away by the National Guard amid an angry mob of white adults and students. The next day, photographs of fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Ann Eckford being hounded off the campus as she cradled her school books appeared in newspapers around the world, providing a catalyst in ongoing efforts to desegregate public schools in the United States. Living in Los Angeles, Domingo Ulloa (1919–1997) saw these images and almost immediately painted Racism/Incident at Little Rock 1957.

Domingo Ulloa

Braceros 1960

Oil on masonite

© Elsa Ulloa. Photo: Courtesy Autry National Center, Los Angeles

Working in the social realist tradition, Ulloa foregrounded Eckford alongside five other black children, depicting the mob in Surrealist style as white frog-like figures with exaggerated mouths, and no eyes or ears. The image, Norman Rockwell meets Salvador Dalí, captures the emotional impact of the news photos, shifting viewer identification from an aggrieved white citizenry to the black children to whom the American Dream has been denied. In the decades before the civil rights movement, racial segregation in schools, restaurants and public spaces targeted both the African American and Mexican American communities.

Ulloa, as with other Mexican-American artists born between the 1910s and 1930s, is part of a hyphen generation that developed what curator and writer Terezita Romo calls a “bicultural aesthetic synthesis” of Mexican heritage with American art. Their work drew on personal experiences, but it was also global in orientation and often experimental in form, exploring the uncharted spaces between Mexican tradition and American modernism.

As an artist, Ulloa was classically trained in Mexico in the 1930s, and, after serving in the US Army in Europe during the Second World War, returned to Los Angeles, where he studied with Italian-born Rico Lebrun, an influential figure in the city’s emerging art scene and its emphasis on figurative expressionism and hard-edge abstraction. Ulloa’s iconic painting Braceros (Mexican Labourers) 1960 drew upon his visits to a bracero camp in San Diego County, depicting individual faces peering through a barbed wire fence that defines the picture plane, thereby reducing the space between subject and viewer.

This closeness is by no means sentimental, but rather suggests the viewer’s complicity with the class and racial boundaries established by fence and picture plane, labour policy and studio art. The binational Bracero Programme (1942–64) provided temporary contract workers from Mexico to meet labour shortages in US agriculture, caused in part by the wartime internment of Japanese American tenant farmers. Ulloa juxtaposes the individual humanity of several workers, registered in their faces, with the inhumane and anonymous conditions signalled by the rows of hats and shacks in the background. The painting also resonates with imagery of Nazi concentration camps, a subject Lebrun dealt with during his time in Los Angeles. In 1993 the California State Assembly proclaimed Ulloa – who continued to explore social conditions for what he called “the common people in their work, in their joy and their struggle” – as “The Father of Chicano Art”.

In the early 1960s the hyphen generation gained access to the emerging gallery scene along La Cienega Boulevard. While this area is now remembered for the Ferus and Landau Galleries, and the “cool” artists associated with them, ethnic and women artists found support for their “uncool” figurative work at Ceeje Gallery. Its inaugural show in 1962 featured four artists, including Roberto Chavez (b.1932) and Eduardo Carrillo (1937–1997). Chavez’s painting The Group Shoe 1962, based on the photograph used in the exhibition announcement, provides a humorous take on this hoped-for turning point in Los Angeles art. The title resonates with Ed Sullivan’s trademark pronunciation of a “really big show” at the start of The Ed Sullivan Show, which was notable for the integration of black performers into its programming and introducing The Beatles to American television audiences in 1964. Ceeje co-owner Jerry Jerome used Sullivan’s pronunciation to tell the young artists: “It’s going to be a big shoe!” While the title puns on American media culture (and gallery hype prevalent on La Cienega at the time), the “group shoe” directly references Vincent van Gogh’s A Pair of Shoes 1886, a painting that has been central to debates in the philosophy of art, most notably in Martin Heidegger’s The Origin of the Work of Art 1935. Like Heidegger, Chavez’s The Group Shoe finds “under the soles… the wordless joy of having once more withstood want”, but with a crucial difference. If van Gogh had a pair of worn-out shoes, these four artists have just one.

The Group Shoe exemplifies a “bicultural aesthetic synthesis” that combined art history with popular culture, and social activism with continental philosophy. But it also proved prescient with respect to the larger demands of the Mexican-American generation for integration into US society following their disproportionate contributions to the war effort. Neither demands nor contributions would be recognised. By the mid-1960s, a new generation of Mexican Americans, now calling themselves Chicanos, would start a social protest movement focused on farm workers’ rights, educational access, employment opportunity and – once again – disproportionate representation in a new war. On 29 August 1970, the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War attracted more than 20,000 people across East Los Angeles. What began as a peaceful rally ended in a violent police riot and the death of journalist Ruben Salazar, one of the few Chicanos working in the mainstream media. A new wave of Chicano artists, writers and film-makers documented the event and its aftermath, and their work was profoundly shaped by the experience. Salazar’s shooting by an LA deputy sheriff, as historian Mario T García notes, “silenced an expression of hope that American society would keep its promises”.

The conceptual art group Asco (1971–1987) would abstract lessons from the Moratorium about the state, police and media, as well as about the critical potential of the arts to disrupt these power structures. Starting in 1971, it produced a series of conceptual performances that challenged police restrictions on Chicano mobility and public assembly in East Los Angeles. In First Supper (After a Major Riot) 1974, Asco members occupy the same street on which Salazar was killed. The performance signals not so much the religious sacrifice of the Last Supper – and its many artistic renderings in Christian art – but the start of an art practice distinct from social protest, yet addressing many of the same issues. As Asco member Patssi Valdez recalls: “Because of the way we looked [as Chicanos], I must have gotten stopped by cops 25 times in one year alone in my neighbourhood. It finally got to the point where I used all these things that were bothering me – police brutality, racism – to write, to make statements.” Core to these actionsas- statements is the idea of elaborately costumed artists doing something activists could not: occupy public space to make a point about the limited pathways available to the Chicano community.

The emergence of Chicano art in Los Angeles, as in many other urban centres, was sparked by the desire to reclaim public space in the wake of urban renewal and post-war policies that cut through the artists’ communities with freeways. In East Los Angeles, Goez Art Studios and Gallery took over an old meatpacking warehouse; Mechicano Art Centre, after moving from its first location on La Cienega, made its home in a former laundromat that it leased from East Los Angeles Doctors Hospital; Self Help Graphics & Art eventually inhabited a space owned by the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and previously used by the Catholic Youth Organisation; and Plaza de la Raza converted the abandoned boathouse at Lincoln Park into the cornerstone of an arts campus. The Social and Public Art Resource Centre (SPARC) was founded across town in the old Venice jail. Rather than erase all traces of the cells, SPARC reconfigured them as gallery space and invited the community – including those who had been incarcerated there – to reengage with it on new terms through collaborative public art.

SPARC co-founder Judith Baca – like many of the artists involved in community organising – worked across racial and generational lines, organisational affiliations and artistic media. She participated in exhibitions and programmes at the Woman’s Building, and was involved with its predecessor, Womanspace, and with the Feminist Studio Workshop. Mechicano co-founder Victor Franco formed the Los Angeles Community Arts Alliance in 1971, co-ordinating efforts among 51 community-based art groups spanning all races and neighbourhoods to promote “the arts as a tool for social change through education”. Mechicano director Leonard Castellanos later formed cooperative strategies and alliances with John Outterbridge (Watts Towers Arts Centre) and community curator Cecil Fergerson.

In the 1970s the primary visual forms that emerged – murals, posters and photography – were also those that could reach the largest number of people, creating the cornerstone of community making through art. These new art spaces reflected the different aesthetic projects for each group. For Goez, co-founder Johnny Gonzalez’s mural design borrowed the compositional strategy that Michelangelo used inside the Medici tombs, but it also drew upon the approach of the Mexican muralists who integrated site architecture into their work. Thus, he placed the two figures – Cortez and Malinche, representing the cultural origins of Chicano art – as if they were lying on the window sills. Goez artists also produced elaborate architectural plans combining Aztec and modern designs for civic spaces and commercial centres, while re-imagining the freeways as the basis for heritage tourism. In contrast, the Mechicano’s façade displayed a wide array of artistic styles by younger male and female artists, while murals and posters often utilised a hard-edged painting style, reflecting its role of pushing experimentation.

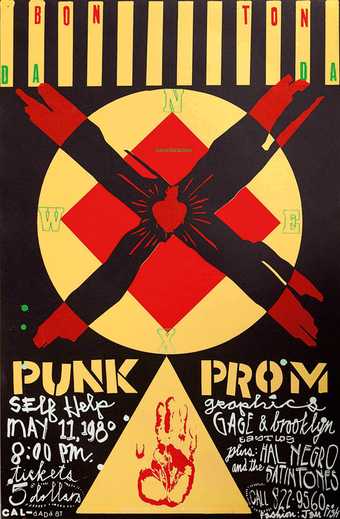

Richard Duardo

Punk Prom 1980

Silkscreen print

89.5 x 58.6 cm

Courtesy Self Help Graphics & Art, Los Angeles © Richard Duardo. Photo: Jenny Walters

Chicano artists gained inspiration from the barrio, but they were also fully engaged with the history of art, freely adapting historical styles to new purposes. They moved adeptly through neoclassical approaches, Mexican social realism, neo-Dadaist principles, hard-edge abstraction and graffiti aesthetics. Leonard Castellanos’s Guerra 1976 – part of a series of silk-screened calendar prints – features a highly stylised design reminiscent of Soviet propaganda posters of the early twentieth century, contrasting with the calendar cover, a supergraphics image based on his iconic RIFA, a serigraph portrait of Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata created in 1972. Functioning as fine art print and event announcement, the hard graphic edge of printmaker Richard Duardo’s Punk Prom (1980) heralds The Vex at Self Help Graphics as a new meeting ground for a Chicano punk subculture that often found itself excluded from Westside venues. Duardo would also co-found the independent record label Fatima Recordz with music promoter Yolanda Ferrer and musician Tito Larriva of the band The Plugz.

While Chicano artists have obvious influences from and continuities with the hyphen generation, the sheer scale and pace of change cannot be overstated. In 1970 alone, they appeared in as many exhibitions in Los Angeles as had their Mexican- American predecessors over the previous quarter century. The earlier generation had made headway into gallery row on La Cienega, largely due to Ceeje Gallery. In 1970 Chicano shows came mostly from art spaces at local public colleges and libraries responding to the student movement. The newly established Mechicano Art Centre accounted for a quarter of the exhibits. Located at the time on La Cienega, Mechicano would move to sites on the east side starting in 1971. That year, Goez Art Studios and Gallery held its inaugural exhibition, followed by other community-based arts organisations. Artist Gilbert “Magu” Luján Sánchez was also pivotal in organising early Chicano art shows, including the first at a major art museum (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) in 1974, which followed closely on two exhibitions of black artists that were the result of concerted efforts by African American employees at LACMA, who formed the Black Arts Council (1968–74).

By early 1975 Chicano artists had produced nearly 300 murals and wall decorations across East Los Angeles, and Judith Baca had initiated the Citywide Mural Programme (the city-run precursor to SPARC). In response, Goez published a “map guide” identifying these works, envisioning East Los Angeles as a cultural destination, rather than simply accepting or rejecting its designated status as a pass-through zone for suburban commuters. An inscription on the map turns the cultural logic of empire (where a centre controls the margins) against that of urban renewal (defined by white flight from urban centres): “In Europe all Roads lead to Rome. In Southern California all Freeways lead to East Los Angeles.”

Roberto Chavez

Porque Se Pelean?

Detail of mural, Eastern and Floral, East Los Angeles (1972)

Regents of the University of California, Courtesy UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Library © Roberto Chavez. Photo: Photograph Nancy Tovar Collection

In 1972 Roberto Chavez painted an anti-war mural in East Los Angeles. Porque Se Pelean? (Why Do They Fight?) depicts war through cartoonish weaponry, surreal figures and animals, and skulls alongside anthropomorphic flowers. Beneath the imagery he signs his name as well as those of the local youths who watched him paint (and who might otherwise have tagged his mural). As a college instructor in the 1970s, Chavez would mentor younger Chicano artists, including Joe Rodriguez, who later joined and then directed Mechicano. Almost four decades later, archival artist Sandra de la Loza discovered a slide of this mural in the Nancy Tovar Collection at the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Centre during her own research on Chicano muralism. The image stood at the intersection of the more canonical didactic work produced by Chicano art groups and the often overlooked decorative, landscape and psychedelic murals painted by local residents. Using a kaleidoscopic program, she animated the image, turning it into an arabesque design and an image machine, borrowing and mixing the older visual elements to create something new… and perhaps conjuring up the other shoe.