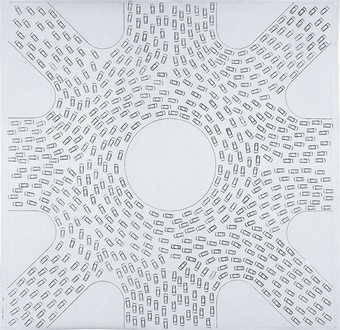

Dor Guez on Leon Ferrari’s Roundabout II 1981

León Ferrari

Roundabout II

(1981, 2007)

Tate

When I was thirteen my parents took me and my brothers on a holiday to the UK. It was our first visit, and my dad planned an ambitious road trip. We started in London, where my mom’s aunt, Georgette, had lived since 1948. She was exiled from Palestine at the same time as British Mandate soldiers left the Holy Land. Georgette was considered to be one of the most beautiful women in Palestine. She was particularly fond of my mom, as they both inherited the family trademark - Mediterranean blue eyes. Thanks to her deceptively ‘European’ looks, my Middle Eastern great aunt assimilated in Great Britain with ease. We used to refer to her as ‘her Majesty’ behind her back. From her English-style cottage in London we were ready to conquer the country with a short-term rental car. We hit the road, imagining ourselves to be adventurous explorers in an exotic faraway land.

Unlike the royal Georgette, our driver, my usually cool-tempered dad, could not adjust to British rules, especially those pertaining to traffic. Clearly, the British drove on the wrong side of the road, and our driver was left alone to deal with the realities they had shaped. My dad, who is fluent in six languages, half of them Semitic, gave us all a lesson on how to curse the empire in all six. Much to our amusement as we sat in the back of the stray ‘wrong sided’ car, his acrobatic verbal commands expressed a feeling of acute disorientation. Things got worse when we headed north and couldn’t understand the accent of those who tried to instruct us. What or where is this ‘roundabout’ they send us to over and over again? This notion of roundabout traffic intersections was only imported to our region in the past decade, and for us, short- term visitors in short- term rental cars, on the wrong side of the world, it all seems foreign.

Dor Guez is an artist based in Tel-Aviv and founder of the Christian Palestinian Archive. With thanks to the Outset Contemporary Art Fund.

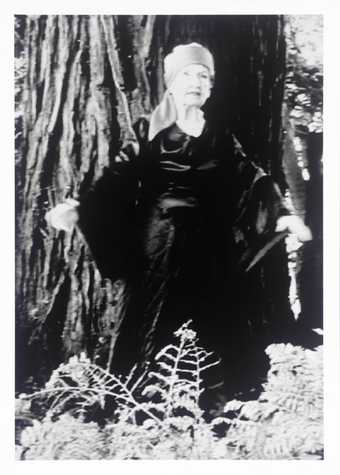

Milovan Farronato on Trisha Donnelly’s The Redwood and the Raven 2004

Trisha Donnelly

The Redwood and the Raven

(2004)

Tate

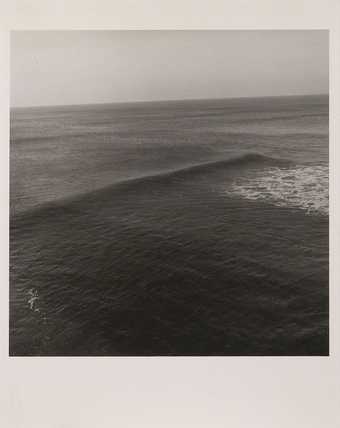

Irregular patterns and modulations as sinuous as the charming of a snake; as giddy as crevasses in a glacier; as vapid as an undertow; as heavy as clods of earth. Flayed texture: flesh, blood and excrement. Dehydrated drapery and deep scars.

The shroud of my prison has been growing thicker for a century now. Forced into vertical exile, I touch the sky and then sink once again into a well whose rocky walls congeal around me. No way out, no footing, on the pillar of nothing and in the abyss of naught.

Like all those wide-open doors that I’ve interred in 160 rooms so that they would not lead Anywhere Else. Blind corridors. Entrances with no access and windows that face on to other windows that open on to an obstruction. Skylights inside skylights. Ladders climbing into empty burial niches. Severed branches. Suddenly blocked paths. Thirteen strokes at the thirteenth hour of the thirteenth of every month. No illusion, no grace, but a corrosive and unchecked hypertrophy degenerated into neoplasm. A mawkish maze of the mind to disorient troubled spirits. And now, in my turn, locked up in retaliation, I call for someone who in 31 moves can help me to placate my prison. I wait, trustingly, for the shadow to disappear from my exhausted bark. Maximum light, minimum shade. Someone fasting with a clear conscience will crumble and roll away the stones. The hunt will be wild and what stood still might flee. My pupils still long for an impression to engrave itself on the back of the eye, beyond the ornamental repertoire of my seclusion. Skin eaten away by the sun, dried up, desiccated, flayed.

Milovan Farronato is curator at the Fiorucci Trust.