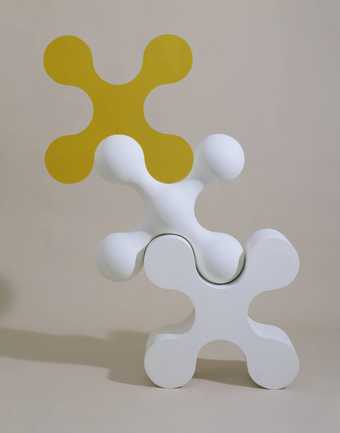

Phillip King

Tra-La-La

(1963)

Tate

Phillip King has the most original imagination of anyone I know, and the sculptures he created in the early 1960s are among the most original of the twentieth century. We first met in 1960 at an exhibition at St Martin’s School [now Central Saint Martins] of constructions in steel and wood I had recently made there. Phillip was working for Henry Moore and teaching an evening class. We talked a lot, then and later, about what sculpture could be if it were not an image of the figure. My ideas came from Rilke and Hannah Arendt: I thought sculpture could be an object among other objects in the world, with their clarity, but with a unique identity, and with, as Phillip put it, ‘a familiarity which resists recognition’. I didn’t see his work for quite a while. He hinted that he had been inspired by a recent journey to Greece to take a pause and completely wipe the slate clean – to start from the beginning; to make, in a sense, the first sculpture.

Change was in the air. All the artists I knew talked only of American painting, then being shown in London in a series of great exhibitions. The example of Franz Kline suggested how the energy and vitality of this work could be carried over into sculpture, applied to construction in wood and steel, as in the first show of Mark di Suvero in New York. Tony Caro had just returned from the US and was putting together horizontal assemblages of found steel sections.

When Phillip eventually invited me to his studio in the attic of the huge house he lived in on Parsifal Road in West Hampstead, I didn’t know what I was expecting, but what I encountered was amazing and quite different from any sculpture I had ever seen. It could have been Window Piece 1960–1, Rosebud 1962 or Drift 1964, or any one of a succession of truly marvellous things that I saw on visits over the next year of two. The first pieces were in concrete, then he discovered fibreglass (he’d used it to build a boat and realised its possibilities for sculpture). There was no evidence of process - it was as though each piece had been thought into existence complete and unique, unlike anything that had ever been made before.

Of course, these sculptures must have had some precedents somewhere. If Tra-La-La has an ancestor, it has to be a Brancusi Bird. I suspect, however, that the origin of this piece for Phillip came from squeezing a lump of clay into a cone with two hands, drawing a swelling bead out of its point, which then becomes a column, turns at a right handle, meets a descending column and twists around it. Or maybe the clay started in the air and went through these changes arriving at the ground, where it spread into a cone. But in the sculpture itself there is no succession of events. Everything is presented simultaneously, hovering in the space opposite you: a presence, neither a figure nor an object, more like a dream.