The modern world thinks of art as very important, something close to the meaning of life. Yet our encounters with it do not always go as well as they might. Sometimes we leave museums underwhelmed, or even bewildered and inadequate, wondering why the transformational experience we anticipated did not occur.

It is natural to blame oneself for experiences of art that don’t touch one deeply; to assume that the problem must come down to either a failure of knowledge or of a capacity for feeling.

The problem isn’t always our fault. Some of the blame lies in the way that art is presented to us by museums. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, our relationship to art has been weakened by a profound institutional reluctance to address the question of what art might be for. This is a question that has, quite unfairly, come to feel impatient, illegitimate and a little impudent.

The well-known phrase ‘art for art’s sake’ specifically rejects that it might be for the sake of anything in particular, and so leaves the high status of art mysterious – and therefore vulnerable. Despite the esteem enjoyed by art, its importance is too often assumed rather than explained. Its value is taken to be a matter of common sense. This is highly regrettable, as much for the viewers of art as for its guardians.

I’d like to propose that art has a purpose that can be defined and discussed in plain terms: it is a therapeutic medium that can guide, exhort, strengthen and console its viewers, helping them to become better versions of themselves.

In any number of situations there are works of art that we should look at in order to rebalance our characters, recover calm, rediscover hope, expand our capacities for empathy and learn to appreciate the everyday. No less than music or literature, the visual arts have a role to play in keeping us more or less sane and in restoring us to a measure of serenity in an often frenetic and disappointing world.

Without necessarily meaning to, museums send out subtle cues about what the ‘right’ thing to do inside them is. This set of norms is chiefly communicated by the captions which accompany objects and which throw the emphasis on a particular set of concerns: the name of the artist, the school to which they belonged, the influences upon them, the material of which the art object is made and their place within the museum’s internal cataloguing system. In other words, the captions invite their readers to take their first steps in adopting some of the concerns of the curatorial and academic establishments that, behind the scenes, look after and interpret works in museums.

I am interested in re-framing works of art so as to draw attention to their therapeutic aspects. Here’s how this might happen with four of the works in Tate Britain’s rehang:

1. Sir Nathaniel Bacon, Cookmaid with Still Life of Vegetables and Fruit c.1620–5

Sir Nathaniel Bacon

Cookmaid with Still Life of Vegetables and Fruit

(c.1620–5)

Tate

The idea of consumerism as evil is a scourge, ready to hand, with which to beat the modern world. Yet consumerism doesn’t have to be stupid or cruel. At its best it is founded on love of the fruits of the earth, delight in human ingenuity and due appreciation of the vast achievements of organised effort and trade. This painting takes us to an instructive time when abundance was new and not to be taken for granted. The picture knows it is hard to grow fruit and vegetables. The people who liked this sort of work were still amazed – as we should be – that they could control the world enough to have so much fruit; that you could get all those varieties of vegetables. They knew how astonishing it was that human beings could lay aside their usual squabbles and indolence in order to produce such bounty. They felt the beauty of trade and agriculture and understood how easily it could be disrupted by sickness or war. The picture remembers effort and celebrates it.

We are so afraid of greed that we forget how honourable the love of material things can be. In 1620 (when the painting was made) homage could still be paid to the nobility of work and commerce; something which boredom and guilt make less accessible to us today. Perhaps we can learn from this picture. A good response to consumerism might not be to live without melons and grapes, but to appreciate what really needs to go into providing them. Our desire to have luxury cheaply is the real problem. If the route to your table were dignified and honourable at every stage, a melon would – of course – cost more. But maybe then we would stop taking it for granted, and our appreciation of its flavour would be all the keener.

2. William Dyce, Madonna and Child c.1827–30

We’ve seen this kind of thing so many times, it’s easy to get anaesthetised to what’s actually going on: which is that a mummy is being really nice to her young child in an expensive and prestigious public object painted by one of the most talented people of his time and now endorsed by one of the most powerful public institutions of our own.

So much of growing up is about becoming independent and getting by without the comfort on offer here. Being a mummy’s boy remains a stinging insult to our autonomy. But this is an exaggerated repudiation of an important need. Christianity is kind and delicate to our longings. It allows us to get in touch with vulnerable emotions without pointing the finger at us. One can participate in the comfort of Mary without needing to give up the hard won advantages of adult life. The painting reconciles us to a longing that might otherwise unman us, that could undermine our claims to an adult identity (it might help our identification that the baby looks about 27).

Adult life involves moments of panic and distress when rational argument isn’t enough. What we really need is to be held and reassured, looked on kindly and shown a beam of unconditional love. This loving look is what can recharge us to go back into the battle or, more likely, the office. It’s on offer here.

3. Sir William Quiller Orchardson, The First Cloud 1887

Sir William Quiller Orchardson

The First Cloud

(1887)

Tate

We’re often not 100 per cent sure what we’re supposed to do in an art gallery (other than not shout and look for the artist’s name), and our lack of direction leaves us grievously vulnerable to getting bored. We know from the rest of life, especially from restaurants and pavement cafés, what fun it can be to speculate on the basis of nothing more than appearance what certain people are like – what their lives might hold, what it might be like to be friends with them and how their relationships are going.

This should be recognised as one of the main things we should be doing with art in museums. Its prestige should be up there with knowing the date and historical influences.

In this case, look past the slightly unfamiliar clothes and oddly sylvan setting, and you have two people who perfectly invite, and reward, such speculations. Why did they get together? What has gone wrong? How might this fight play itself out?

Relationships are painful for almost all of us – yet often the pain is increased by thinking (quite wrongly) that we’re the only ones to squabble, get bored, behave badly, or nurture regrets. Orchardson’s painting places our woes in context. It should belong to a whole gallery of works one might title: ‘What love is really like for other people.’ Our friends don’t tell us. Movies lie too. So much of love is corrupted by false, sentimental images of what is meant to happen in couples. They get us into trouble. Orchardson’s picture may be sad, but because it is realistic about what can happen to fundamentally rather nice people in love, it helps to reconcile us to the dimensions of reality and therefore paves the way to a highly necessary and useful education about relationships.

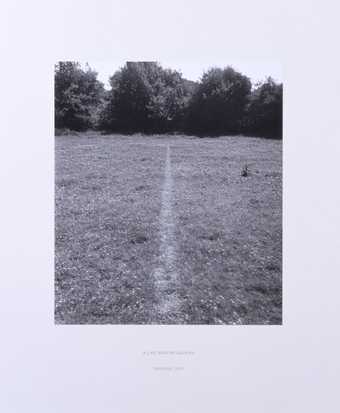

4. Richard Long, A Line Made by Walking 1967

Richard Long CBE

A Line Made by Walking

(1967)

Tate

We are so familiar with the idea that nature is attractive that it can be a struggle to recollect that often in the history of humanity, and in our own individual experience too, it hasn’t seemed at all obvious that it is worth admiring. Mostly it is not that we dislike nature, it is just that other concerns are much more pressing or immediately rewarding.

Art is a record of good observation, which should encourage us to follow its spirit, even if only a few of us end up replicating its products. For many decades now, the British artist Richard Long has been memorialising his walks around different parts of the natural world. He has laid down markers, erected stones and listed his walks’ time, place, route and the prevailing meteorological conditions. Many of his walking diaries have been written up in solemn fonts on large framed prints (some many metres high and wide). The effect is incongruous. We expect this sort of treatment to be accorded to the commemoration of a battle or the efforts of a national government. That it is merely a walk by an ordinary citizen is an argument for us to reconsider the value of this sort of activity.

Long doesn’t tell us what he thought about or felt when he walked up and down an ordinary English field. We are left – intriguingly – to imagine. His concern is more elemental. The photograph and minimal, august, refined lettering convey the dignity he rightly feels that his walks (and ours) deserve. He wants us to recognise that some walks can be central events in our lives; our inner transitions assisted by our outer wanderings.

It lies in the power of art to honour the elusive but real value of ordinary life. It can teach us to be more just towards ourselves as we endeavour to make the best of our circumstances: a job we do not always love, the imperfections of middle-age, our frustrated ambitions and our attempts to stay loyal to irritable but loved spouses. Art can do the opposite of glamourising the unattainable; it can reawaken us to the genuine merit of life as we’re forced to lead it. Aside from telling us the date and provenance of works, that’s also something that the museum should talk to us about slightly more often than it does.