Richard Hamilton

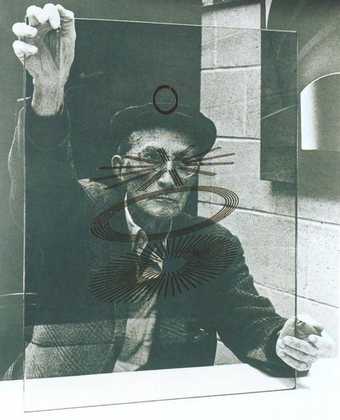

Marcel Duchamp

(1967)

Tate

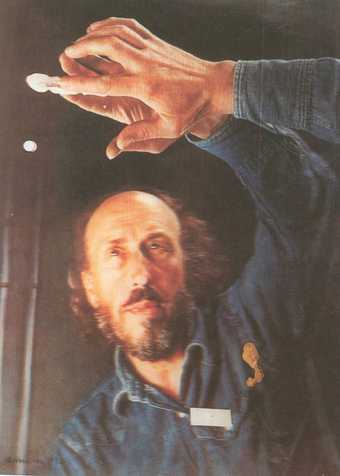

Richard Hamilton

Palindrome

(1974)

Tate

He Loved Him Madly, title of Miles Davis’s tribute to Duke Ellington on his album Get Up With It 1973

Studying in London from the late 1930s to the beginning of the 1950s, first at the Royal Academy Schools and then the Slade, Richard Hamilton had amassed skills and technical expertise in a myriad areas of art-making, from painting and drawing to printing, etching, anatomy and perspective. En route, in discussion with other students and acquaintances, he essayed what might have been regarded as more arcane, intellectual-theoretical areas, such as morphology and exhibition design. It was a time of debate and division within the visual arts: of a stand-off, perhaps, between the creeds of figuration and abstraction, the ‘modern’ and entrenched traditionalism.

From the outset, the nature of Hamilton’s art was to open up the creative properties of process, and in a way that made process itself both a medium and a subject - monitoring, on the one hand, with scientific attention, the nature and progress of its gradations, and on the other releasing a new aesthetic of the modern world, as erotically glamorous as you like, from what had first appeared a position of near-clinical, technical detachment. And in this Hamilton brought a quality of inestimable importance to contemporary art: a mind that was wholly in tune with the times, embracing all that was most vivacious, technologically advanced or ingenious.

And he did this in a witty and stylish way, engaging with the burgeoning Mass Culture of Pop (as in populist) in much the same way as an artist of the previous century might have engaged with Nature. He would later remark that while teaching at Newcastle University, from 1953 to 1966, he learned more about the machinations and sociology of pop culture from going with his students to the lunchtime dances held in the city’s ballrooms, such as The Majestic (this during the earliest days of Mod), than he did from all the meetings at the ICA of the notably fractious Independent Group. However light-hearted the remark, it seems clear that in his relation to Pop, Hamilton worked directly, so to speak, from nature - fascinated by the technological-industrial-artisanal processes of mass culture, and their relation to a fine artistic vision.

In the development of his art and ideas through the 1960s and 1970s, Hamilton’s genius apparently lay in the holistic nature of his trans-media conceptualism, while his concentration on process and technique could in part be an alibi for his actual, more poetic concerns. From this it appears scarcely surprising that he would both admire and arguably equal, artistically, the achievements and iconoclasm of both James Joyce and his great friend and collaborator, Marcel Duchamp.

In Duchamp, perhaps, Hamilton found his Mozart. An artist-conceptualist-technician-philosopher-iconoclast, Duchamp provided him on one level with a template for intellectual and artistic strategising - not to imitate (a cardinal sin within Duchamp’s ideology), but rather:

…The major influence he [Duchamp] has had on me is a kind of reaction against him - not in any sense being anti-Duchamp but in accepting his iconoclasm, the fundamental aspect of his work. There’s one way to be influenced by Duchamp and that’s to be iconoclastic - against him. He was, for example, always anti-retinal. Now I’m turning away, becoming more ‘retinal’ in my painting, and thinking that’s the way Marcel would like it.

Reconstructing Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1915-23 in the mid-1960s was for Hamilton a technical and intellectual operation of staggering complexity - at once devoutly, almost perversely concerned with the practicalities of decipherment and craft, yet at the same time inhabiting empyrean realms of psychology, aesthetic philosophy and enacted myth. An absurdist sexual allegory, ‘crammed with incident and riddled with blind alleys’, The Large Glass at its most simple could be seen as a precursor of early Pop’s devotion to ecstatic frustration: Halfway to Paradise as Billy Fury put the case in his 1961 UK hit of that name; likewise a diagrammatic rendition of Pop’s basic sociological formula, Pop = Sex + Mechanisation.

Balance and confluence are key, it seems, to both Hamilton’s vision as a thinker and his development of process as an artist. And what of beauty? In his great last untitled work, known in studio shorthand simply as The Balzac 2011, Hamilton engaged directly with what for him was the totality of being an artist - and how, perhaps, that vocation might stand in relation to a quality as elemental and complex as ‘beauty’. Inspired by Honoré de Balzac’s allegorical short story The Unknown Masterpiece 1831, with its co- joined themes of artistic and erotic desire, Hamilton’s untitled underlined his career-long analysis of conceptual, aesthetic, intellectual and philosophical ‘perfection’. This was a quest - pursued through resolving process, in the glossy sheen of one of his Toaster or Swingeing London series, or the ultra-violet blur of an angel’s wings in his Passage of The Angel to The Virgin 2005-07 - which, like the eternal manoeuvres of Duchamp’s bachelors and bride, or the figures on Keats’s Grecian urn, or F Scott Fitzgerald’s boats beating on against the current, could only be achieved by its very impossibility. And thus Richard Hamilton, artist, achieved the impossible.