Lee Ufan at work in his Paris studio, February 2014

Photograph © Simon Grant

Sook-Kyung Lee

We are in your Paris studio, so can I begin by asking you how you made one of the works we see here?

Lee Ufan

To make a painting I work with the canvas lying on the floor. I paint a single stroke about three of four times, leave this to dry for about a week and then repeat the process, which takes about 40 days. When I am painting, I have to hold my breath for about one to two minutes to make the brush stroke straight. When people come to see me work, they have said they feel breathless. It’s an interesting phenomenon. If I am working very slowly, it becomes obvious that I’m not breathing, so this type of tension has to become apparent. When you feel this tension, or breathing’s power, a vibration arises - this is the most important thing, not the work itself. The size of the whole canvas is the issue, and in particular the space surrounding the painted stroke. The painting works only when the entire space’s vibrations resonate together, and not just the brush stroke.

Sook-Kyung Lee

You have lived in both the East and West. Do you think your comparisons from going back and forth between two cultures have made a difference to how you make your work?

Lee Ufan

Yes. At first I didn’t consciously make comparisons. But as I travelled around, I’ve become used to living and thinking alone. Despite having been born in Asia and growing up there, much of my education was Western, and because I’ve been traversing Europe half of my life, it’s difficult to stand on one side or the other, although, strangely, standing on either side also feels very natural to me somehow. And as much as I’d like to believe that my thinking is very cosmopolitan, at times people are able to discern that I may be coming from somewhere deep within Asia. Occasionally, I resent and resist this, but it’s something that I cannot really control. However, I oppose the idea that I somehow sell the idea of Asia, or that I sell the idea of modernism. Sometimes my works are described as Zen Buddhism, but I don’t know either Zen or Buddhism very well. Those terms actually contribute to the misunderstanding of my work.

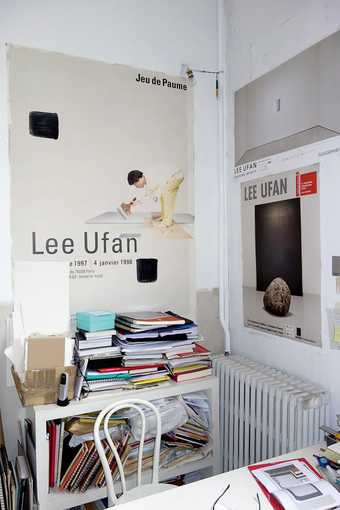

A corner of Lee Ufan’s Paris studio, February 2014

Photograph © Simon Grant

Sook-Kyung Lee

It seems to me that painting and sculpture occupy separate domains in your practice. Why is that?

Lee Ufan

I tend to be a bit too ambitious. I am tempted to dabble in literature, and I would have also wanted to play and compose music. I wanted to try my hand at architecture too. When I make works thinking ‘art must be at the centre of my thinking process’, my thoughts are not being formed, as is, into either paintings or sculptures, but rather they use my thoughts partly as a pod to encapsulate something beyond my own thoughts, or, to put it differently, it’s about painting through the relation between the painted and the unpainted. And for sculptures, I think about expression through the duality of the made and the unmade. Consequently, there’s a part that cannot be captured only through painting, or only through sculpture. Paintings are not solely the product of my thoughts - rather, they are made to connect to the outside. But at the same time, a big part of painting is a direct expression of what’s inside me, internally. In comparison, sculpture is quite open, whether it deals with one’s relation to the other, or the relationship between spaces and materials.

Sook-Kyung Lee

Your work is often associated with the Mono-ha movement in Japan. How did this come about, and what are your memories of it?

Lee Ufan

In the second half of the 1960s, industry in developed areas of the world such as Europe and the US, or in the case of Asia, Japan, grew at a hyper-accelerated pace. The May 1968 student protests in Paris and the countercultural movement in New York around 1967 and 1968 were indications that all that could be achieved with modernity’s growth had been achieved. At the same time in Japan, it was the intellectuals who were protesting about the breakdown in society’s values. Consequently, a discussion arose regarding production, or the act of making. I’m not Japanese, but as someone from the outside, I thought I should be a part of this. We believed that the unmade needed to be introduced, rather than something that was made. To give you an example, a rock, a natural stone, is not made, but can be as old as the earth. So in an effort to break away from the conventional way of thinking that concentrated solely on making and look at things anew, we asked: how does bringing in the unmade open up a new dimension of expression and change both the made and the unmade? That movement became Mono-ha. The name [Japanese for ‘thing school’] was coined by a journalist, and it stuck. It was a way of saying: ‘Those bastards can’t make anything, and can’t paint.’ Initially, we resisted the term, but it spread around the world and became standard. It’s actually not too bad a description, because it refers to displaying an object without a known maker. And we were not presenting an object; rather, we were examining the relationship between object and space, or between object and object. Around the same time various other movements appeared, such as Arte Povera in Europe and earthworks and Minimalism in the US. In other words, what’s important to note is that Mono-ha was Japan’s own version of an international movement.

Sook-Kyung Lee

You are currently working on a project at Versailles…

Lee Ufan

The garden was designed by André Le Nôtre, the exceptional mid-seventeenth-century landscape architect. In Europe, gardens have traditionally been constructed architecturally, based completely on man-made concepts. They don’t work with nature’s principles, but rather make nature just another subject and material for man’s use. This is something that could never happen in Asia, where organising or trimming the garden is in concert with nature. As an Asian person, I felt that Versailles was too overwhelming.

So what could I do there? For me, it has again been a question of bringing together the idea of the made and the unmade. How could I reveal something that most people don’t think they see? How do I make a space that has duality? During several visits I discovered a hidden part of nature there that doesn’t take on man’s form. There is a long lawn section that extends for about 300m, and one day, by chance, a gentle wind swept through the grass, moving it like a wave. And I thought: ‘Ah, I should make a wave-like work here.’ Such a moment passes by in an instant, and is bound to be forgotten. An artist’s ambition should be to take that moment, to extend it indefinitely, and to make it accessible. So I am installing an extensive curvature, and when you pass through it, another space beyond the normal perspective will be revealed. There, the neutral space of the sky and the surrounding space will look completely different.