David Hockney photographed by Snowdon in London, 1978

Photo: Snowdon/Trunk Archive

David Hockney (b.1937) remains one of the most celebrated and popular British artists of the 20th century. For more than 60 years he has been breaking boundaries in the media he has used, including painting, drawing, print, photography and video. Central to this approach has been the artist’s fascination for people and places as well as his ongoing enchantment with the art of the past.

‘I don’t think there are any borders when it comes to painting,’ David Hockney said recently, ‘I’ve always thought that. There are no frontiers, just art.’ We were talking about links between East and West – the links, for example, between the woodblock prints of Japan and the paintings of van Gogh or the films of Walt Disney. But the remark also applies to Hockney himself. It is hard to think of a comparable figure who has ranged so far in space – and time.

He has wandered over the globe, visiting and working in an astonishing number of different places: Iowa, Lucca, Colorado, the Arctic north of Norway, rural France, New York and Kyoto, for example, as well as Paris, London, Bridlington and Los Angeles. A selection of titles, chosen almost at random from the forthcoming exhibition at Tate Britain makes the point: The Great Pyramid with Palm Tree and Car 1963, Place des Canons, Beirut 1966, Kasmin in his Bed in his Chateau Carennac 1967, Study of Water, Phoenix Arizona 1976, Mountains and Trees Kweilin from China Trip 1981. He has been an artist-traveller in the manner of Turner, with his range extended by the use of jet aircraft, rather than stagecoaches and sailing boats.

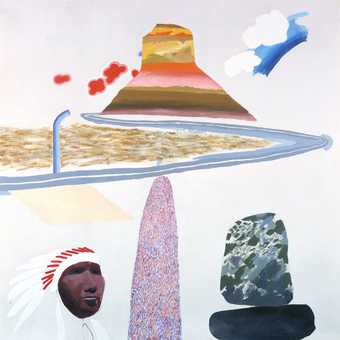

David Hockney, Arizona 1964, acrylic on canvas, 153 x 153 cm

© David Hockney

David Hockney, Place des Canons, Beirut 1966, crayon and pencil on paper, 39 x 49 cm

© David Hockney

David Hockney, Study of Water, Phoenix Arizona 1976, crayon on paper, 40.6 x 45.4 cm

© David Hockney

More deeply, Hockney’s tradition – the line he springs from – is nothing less than what he likes to call ‘the history of pictures’. That is, the entire repertoire of ways in which human beings have tried to depict the world around them from the time of the cave artists 30,000 years ago to digital drawing techniques of the 21st century. His inner reference bank – the images of remembered pictures he draws upon – is correspondingly wide. In conversation, within a few minutes he may move from how a Hollywood movie was lit to, say, the cubism of Juan Gris, or Egyptian tomb painting.

His reach and impact, too, have been international. Marlene Dumas, in the caption to one of her own works, simply described Hockney as ‘one of the great painters of the 20th century’. Recently, the German painter Georg Baselitz – only two years his junior – spoke of the impression Hockney’s early work had on his when he saw it in 1960s Berlin: ‘I greatly admired the works Hockney did at the end of his time at the Royal Collage: wunderbar, amazing, fantastische.’

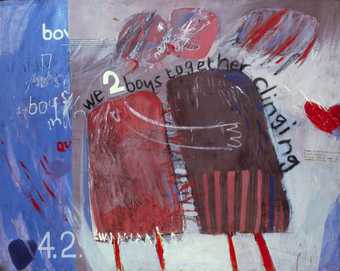

When looking at The Third Love Painting 1960 or We Two Boys Together Clinging 1961, it is not hard to see exactly what the young Baselitz must have seen. Contrary to the orthodoxy taught in West German art schools, which held that only abstraction was valid in the modern age, here was a spectacular demonstration that figurative painting could express the raw energy of being young, the excitement of now.

David Hockney, We Two Boys Together Clinging 1961, oil on board, 121.9 x 152.4 cm

© David Hockney, photo: Prudence Cuming Associates, Collection Arts Council, Southbank Centre, London

David Hockney and Derek Boshier, students together at the Royal College of Art from 1959 to 1962, in front of Hockney’s We Two Boys Together Clinging, photographed by Geoffrey Reeve in 1962

Photo © Geoffrey Reeve/Bridgeman Images

Of course, in his native country Hockney has been accorded the rank – a mixed blessing – of ‘national treasure’. His Yorkshire origins are stressed, and this is not altogether wrong. He is deeply rooted in his native landscape. He was 18, he recalls, before he visited London. In the early 21st century he returned to paint the Wolds of the East Riding, a place he had first seen as a teenager. He talks quite frequently of his early years in Bradford: the trips to the cinema (or rather ‘the pictures’), the relative lack of shadows in the overcast climate of northern England, so different from California, the thorough, old-fashioned grounding in life drawing he had at the local college of art. All this was formative.

There has, however, always been a wider context in which Hockney was looking and thinking. The first great painting he saw, in reproduction, was an Annunciation by the 15th-century Florentine master Fra Angelico. Its influence proved a lasting one, and once you have been given this clue it is not hard to see the lucid forms and clear, bright colours of the quattrocento master in Hockney paintings such as American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman) 1968.

David Hockney, American Collectors (Fred and Marcia Weisman) 1968, acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 304.8 cm

© David Hockney, photo: Richard Schmidt, Collection Art Institute of Chicago

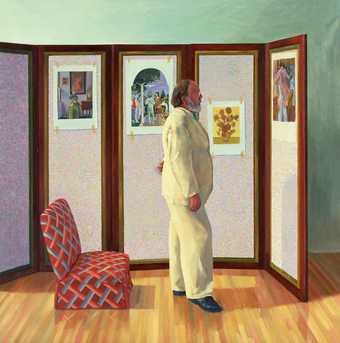

Piero della Francesca’s great Baptism of Christ c.1450s from the National Gallery was another touchstone. It can be seen just behind the figure of Hockney’s friend Henry Geldzahler in Looking at Pictures on a Screen 1977, and turns up again in My Parents 1977 as a reproduction pinned on the wall and reflected in the mirror (along with some drapery which Hockney recently revealed comes from a Fra Angelico). These are private references slipped into the paintings, insights perhaps of what was in his mind at the time. The further images pinned up in Looking at Pictures on a Screen provide a shortlist of some of the artist’s other painter heroes: Vermeer, Degas, van Gogh.

Piero della Francesca, The Baptism of Christ 1450s, egg tempera on poplar panel, 167 x 116 cm

© The National Gallery, London

David Hockney, Looking at Pictures on a Screen 1977, oil on canvas, 183 x 183 cm

© David Hockney

However, the Renaissance was only part of his vast aesthetic hinterland. In 1958 he hitch-hiked to London to see the first exhibition of Jackson Pollock’s work in Britain, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. In Hockney’s early paintings you can see not only the splatter and loose brushwork of abstract expressionism, but also borrowings from the hard edge abstraction that came afterwards (in 1963 a group of British adherents of the trend made a big impact with a show called Situation in London). This was a style derived from Barnett Newman rather than Pollock, and featured clearly defined, flat shapes.

In a picture such as Flight into Italy – Swiss Landscape 1962 Hockney adopted coloured stripes – a characteristic motif of painters such as Morris Louis and Frank Stella. But he wittily unfurled them, like a roll of carpet, across the picture, transforming them into Alpine terrain: an updated subject from Turner. The Cha Cha Cha That Was Danced in the Early Hours of 24th March 1961 performs a similar trick with an arrangement of brightly coloured rectangles that could have been lifted from a Mondrian, circa 1920. These, however, become the backdrop to a frenetically bopping art student. At this early stage he was cheekily reinserting what New York critics such as Clement Greenberg and Hilton Kramer used to call ‘anecdotes’ from everyday life into the pure world of abstraction.

David Hockney, Flight into Italy – Swiss Landscape 1962, oil on canvas, 184 x 185 cm

© David Hockney, photo: Prudence Cuming Associates, Collection Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast, Dusseldorf

Thus, in the early 1960s Hockney was already roving through art history as he put together a distinctive idiom. Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices 1965 is a visual anthology from the Renaissance to late modernism. There are Matisse-like blocks of pure colour, plus the chiaroscuro of illusionistic painting that turns a mass of grey oblongs – abracadabra! – into a pile of cylinders. Half hidden behind these is a seated man in suit and tie, sharply drawn. To the right is a rectangle resembling a picture on the wall, a mass of brown brush marks. An arch and a single shadow create a space-frame like the ones Francis Bacon used in his paintings of the 1960s (Bacon was an older contemporary Hockney talked to frequently at this time).

As so often with Hockney the painting is at once playfully entertaining and highly serious. The mystery it poses is this: when we come across a few tones or colours on a canvas or lines on a piece of paper, somehow we see objects, people and three dimensions. Indeed, we can’t stop ourselves from doing so. Human beings, as the artist says, have a deep need for pictures. They are one of the means of understanding the world around us. But they are also just made up of ‘artistic devices’. One way of seeing Hockney’s art is as a lifelong journey into pictorial space.

David Hockney, Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices 1965, acrylic on canvas, 152.4 x 182.9 cm

© David Hockney, photo: Richard Schmidt, Collection Arts Council, Southbank Centre, London

His true predecessor in this enquiry was Pablo Picasso, who has been, not surprisingly, one of the artistic loves of his life. In the 1950s, when Hockney was a student, the influence of Picasso cast such a gigantic shadow that it seemed almost impossible to escape it. Part of the excitement then about the emergence of Jackson Pollock, Hockney has said, is that here at last there seemed to be an artist who wasn’t derived from Picasso (although, of course, deep down Pollock was too).

Hockney’s own engagement with Picasso began in the late 1960s, and in an unexpected place. He is the only later artist to take Picasso’s neoclassical drawing idiom of the early 1920s – a matter of taut lines, without a single shadow – and use it as a personal means of expression. Perhaps he is the only one with the virtuoso command of drawing necessary to do so and survive the comparison. His W.H. Auden 1968 is as powerful and memorable as Picasso’s Stravinsky from around 1920.

David Hockney, W.H. Auden I 1968, pen and ink on paper, 43 x 35.5 cm

© David Hockney, photo: Richard Schmidt

At a deeper level, however, Hockney was one of the few to take up the challenge of Picasso and Braque’s cubism as a way of seeing the world. The conventional view was that cubism led to abstraction, so it was another means of making a picture, another ‘artistic device’. Hockney, in contrast, accepted that it could be more true to actual experience, because, he believes, we don’t really perceive in the way Renaissance fixed-point perspective presents a scene – nor as a single camera lens projects it. Human beings look from different directions, with two eyes, constantly moving, as we ourselves move around and look, as Hockney puts it, ‘with memory’. This is why Picasso may depict a figure’s front and back view in one image: in the picture you are moving around the subject, having thoughts and feelings about it, just as you would in life.

Hockney’s exploration of cubism was complemented by his encounter of Chinese art, in which – he discovered with excitement – the viewpoint was not fixed as it is in Renaissance perspective or a photograph, but roams through the length of a scroll perhaps 100ft long, over mountains and through city streets, never coming to a halt.

David Hockney, Pearblossom Hwy. 11–18th April 1986, #1 1986

© David Hockney, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Such insights were the basis of his Polaroid and photocollages of the 1980s, which present not one single viewpoint, but hundreds. It took a week to take the shots that make up Pearblossom Highway 1988 – a view of a stretch of road in the desert on the outskirts of Los Angeles. Each of the 850 exposures, Hockney remembers, ‘was taken close to the surface of every element. I was up a ladder photographing the road sign or the cactus. We always took a big ladder, because I knew I needed the ladder – otherwise you have a standard, lens perspective of the object. The markings on the road were done from a ladder, you had to be up above them looking straight down. How do you look at it otherwise?’

Art historian Ernst Gombrich suggested that the result can be seen as an encounter between cubism and photography. Or, as Hockney himself prefers, as a drawing: because it involves putting objects in the space of a picture, and that, he argues, is what drawing really is. It is an investigation that has carried on, using the latest technology.

David Hockney, The Four Seasons, Woldgate Woods (Spring 2011, Summer 2010, Autumn 2010, Winter 2010) 2010–11, 36 digital videos synchronised and presented on 36 monitors

© David Hockney

David Hockney drawing with nine cameras, April 2010

© David Hockney, photo: Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima

The multi-screen films of Woldgate Woods 2010–11 are essentially a moving version of Pearblossom Highway, shot from multiple viewpoints at slightly different times. Similarly, 4 Blue Stools 2014 is a photocollage with smooth, digitally edited transitions between the numerous photographs that make it up.

‘In my beginning is my end,’ wrote T.S. Eliot. There is a deep consistency underlying the multiplicity of David Hockney’s works: a series of enquiries he has pursued for more than half a century. They concern the fundamentals of picture-making and of how we see the world. He has delved deep into the history of art, both Eastern and Western, and frequently used the newest technology as it has become available. He has absorbed and reflected on the picture-making traditions of many times and places, which is one of the reasons why Hockney himself is a figure of global importance.