John Singer Sargent

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

(1885–6)

Tate

In August 1885 John Singer Sargent was on a boating trip with fellow American artist Edwin Austin Abbey when he glimpsed an enchanting scene in a garden at Pangbourne on the banks of the Thames: children lighting lanterns hung among trees, lilies and rose bushes. He described it to Robert Louis Stevenson as ‘a most paradisaic sight’, and it became the inspiration for what he came to call his ‘big picture’.

During the trip, Sargent injured his head in an accident and Abbey took him to Broadway in the Cotswolds, where the American painter Frank Millet and his wife Lily were living, so that he might convalesce. Broadway was a pastoral idyll, and the Millets were a hospitable and gregarious couple who operated as a kind of artistic magnet, attracting a group of painters, writers and musicians around them, so that the village became, for a time, something of an artist’s colony.

Here, Sargent began to make studies for the picture in the garden of the Millets’ rented house, Farnham House, on the green in Broadway. His first model was their five-year-old daughter Kate, but she was replaced by Dorothy (‘Dolly’) and Marion (‘Polly’), daughters of the illustrator Frederick Barnard, who were older and whose fair hair was better suited to the aesthetic of the painting. White dresses were made for them by Mrs Barnard and her sister in the smock-like style of Kate Greenaway’s illustrations.

John Singer Sargent, Sketch for ‘Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose’ 1885, oil paint on canvas, 72.4 × 47 cm

Private collection

John Singer Sargent, Study for Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose’ 1885, oil paint on canvas, 59.7 × 49.5 cm

Private collection

Sargent soon encountered a number of practical difficulties. Autumnal weather meant that the girls had to wear ‘ulsters’ beneath their flimsy white dresses and they found posing annoying. According to the designer Alice Comyns Carr, ‘The little maidens were always loath to leave their play, and John used to fill his pockets with sweets to console his unwilling models for the loss of their cherished last game before bedtime.’

He began to paint towards the end of the flowering season, which meant that he had to ‘scour the cottage gardens and transplant and make shift’ to gather the floral elements of his picture. The American publisher Henry Harper noted that the English weather lived up to its reputation for unreliability when it came to reproducing the appropriate light conditions: ‘Every evening during our visit, just before sunset, Sargent would produce his easel and a large canvas and set them up in the garden, and Fred Barnard’s children would appear in costume ready to pose for him should the twilight meet Sargent’s requirements. Many a time they were out and posing, but the light proved recalcitrant and there would be “nothing doing”, much to the disgust of the children.’

Early in November Sargent returned to London, leaving the unfinished picture in store in Broadway. At about this time, the novelist Henry James, who had visited Farnham House, described the picture as ‘a splendid idea, but he will have to wait to next summer to do anything successful with it. It is now only a powerful auguring’.

By the following year, the Millets had moved to Russell House, a few hundred yards down the road. Sargent was determined to be prepared for this second painting campaign, sending 50 Aurelian lily bulbs for Lucia Millet, Frank’s sister, to plant in garden pots. He set himself the challenge of representing fugitive evening light, the artificial glow of the lanterns and the light reflected on the children’s faces, the whites of their dresses and the lilies. Sargent wrote to his sister: ‘Impossible colours of flowers and lamps, and brightest green lawn background. Paints are not bright enough and then the effect only lasts 10 minutes.’ But he approximated the subtle effects using orange for the glow of the lanterns, peachy reflections for the skin tones, white, mauve and pinks for highlights in the dresses and dusky greens for the shadows.

The process of painting Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose captivated the artistic community at Broadway. One of the temporary residents, the writer Edmund Gosse, wrote a lively account of Sargent’s evening ritual: ‘The progress on the picture ... when once it began to advance, was a matter of excited interest to the whole of our little artist-colony. Everything used to be placed in readiness, the easel, the canvas, the flowers, the demure little girls in their white dresses, before we began our daily afternoon lawn tennis, in which Sargent took his share. But at the exact moment, which of course came a minute or two earlier each evening, the game was stopped, and the painter was accompanied to the scene of his labours. Instantly, he took up his place at a distance from the canvas, and at a certain notation of the light ran forward over the lawn with the action of a wag-tail, planting at the same time rapid dabs of paint on the picture, and then retiring again, only with equal suddenness to repeat the wag-tail action. All this occupied but two or three minutes, the light rapidly declining, and then while he left the young ladies to remove his machinery, Sargent would join us again, so long as the twilight permitted, in a last turn at lawn tennis.’

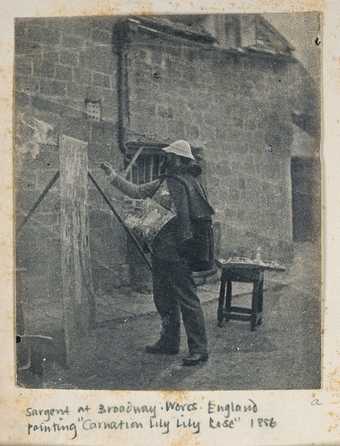

Photograph of John Singer Sargent painting Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose at Broadway in Worcestershire, 1856

Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, photo: Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose is English in conception and in much of its frame of reference – contemporary garden practice, the language of flowers, the culture of childhood – and was produced deep in the English countryside, but its plein-air aesthetic is decidedly French and modern. Sargent offset the artifice of the painting by the speed of its execution – a key aspect of impressionist technique – which he achieved by painting, then wiping or scraping paint off and starting again. In the finished work, he created a background that is refined and transmuted so that the naturalistic garden shown in the pencil studies becomes an enclosed, heightened and allegorical space. Sargent arranged the outsized lilies decoratively rather than realistically around the figures, so that the tall stems and large blooms overwhelm and envelop them. In this he fashioned a sense of activity and energy in the natural world, as broken brushstrokes create swirling grasses and drifts of carnations in the foreground. The rhythm of flowers across the surface echoes the painting’s musical/poetic title, which came from a refrain from a popular song, The Wreath:

Ye shepherds tell me have you seen

My Flora pass this way?

In shape and feature beauty’s Queen

In pastoral array.

A wreath around her head she wore

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

And in her hand a Crook she bore

And sweets her breath compose.

Two pencil drawings of the heads of Dorothy and Polly were probably presentation sketches done after the oil painting, rather than preliminary studies. Sargent gave these to his models, and Dorothy Barnard bequeathed them to Tate in 1949.

John Singer Sargent

Dorothy Barnard

(c.1887)

Tate

John Singer Sargent

Polly Barnard

(c.1887)

Tate

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose was presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest in 1887 and is on display at Tate Britain. For more information on the painting, see http://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/issues/issue-index/issue-2/sargent-co....

Elaine Kilmurray is Research Director of the Sargent catalogue raisonné and co-author (with Richard Ormond) of the nine volumes of the published catalogue raisonné (Yale University Press).