Santu Mofokeng, Dust Storms at Noon on the R34 Between Welkom and Hennenman, Free State I 2007, printed 2011, from the series Climate Change 2007, gelatin silver print on paper, 64 x 98 cm

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation, image © Tate

Over the past decade, whenever we have emailed, Santu Mofokeng has always ended his responses to my journalistic entreaties and gossipmongering with the word ‘care’. Far from a pat formula, the sign off encapsulates so much about this extraordinary South African photographer, whose work confronts social disquiet and ecological unease with distilled sobriety and genuine empathy. Arriving at this defined point involved many renegotiations by Mofokeng as to the role of photography.

In many ways, though, place precedes occupation for Mofokeng, who was born in the township of Soweto, Johannesburg. ‘I have always held Soweto to be the litmus that I use in order to survey or navigate my way through in the world,’ he wrote in a text panel for his 2011 survey exhibition Chasing Shadows at Jeu de Paume, Paris. ‘I feel a peculiar sense of pride and belonging – also grounding – in coming from that space and of contributing to its history.’

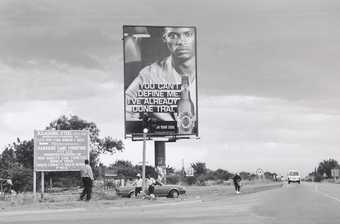

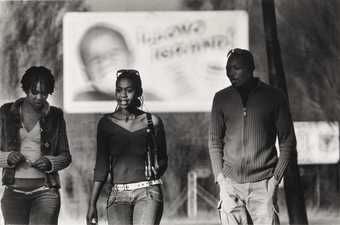

Santu Mofokeng, Street Scene – Rockville c.2004, printed 2011, from the series Billboards 1991–2009, gelatin silver print on paper, 30 x 45 cm

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation, image © Tate

The durability of Soweto as both ‘prism’ and ‘mirror’ is reflected in Mofokeng’s series Billboards 1991–2009, a longterm project made in various black townships, which looks at the conflation of consumerism with freedom by marketers. ‘Previously words such as “freedom” and “democracy” could land you in jail but today they will land you in a shopping mall’, he said in 2013.

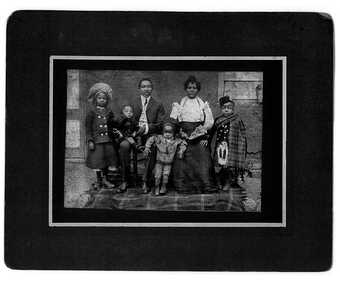

His interest in photography arose in 1960s Soweto, following an encounter with a journeyman photographer, who took Mofokeng’s portrait. He would later pursue a similar career, photographing at events and ceremonies in the early 1970s. It was a precarious vocation, but one that afforded him social status and an income. In 1976, during the violent student rebellion in Soweto, he encountered another way of making photographs. ‘Peter Magubane in 1976 showed that photography could be an honourable, dignified and important career,’ Mofokeng told me in 2010.

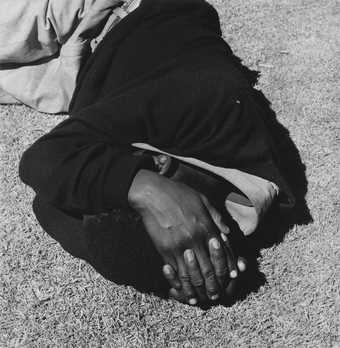

A similar reassessment followed his brief career as a photojournalist in the early 1980s. Friendships with photographers David Goldblatt and Jürgen Schadeberg, and his involvement with the photography collective Afrapix, helped steer Mofokeng towards the photo essay Train Church 1986. This immersive study of commuters on the Johannesburg–Soweto line, showing passengers engaged in religious worship, announced his mature style: exploratory, austere yet lyrical and occupied with quotidian aspects of black life.

It is easy to take the word ‘essay’ as a given in all this. In 1977, in his inaugural lecture at the Collège de France, French philosopher Roland Barthes described his metier, the literary essay, as ‘an ambiguous genre in which analysis vies with writing’. Mofokeng’s essays, including his roaming landscape series Climate Change 2007, draw their strength from a similar ambiguity or tension between imperturbable analysis and Mofokeng’s faith in the beneficial yield that photography offers.

Up until his mid-30s, Mofokeng believed that documentary photography still functioned in the way it had for photographers like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine in ‘exposing social maladies’. It doesn’t, or at least not with its former impact; and yet, photography still matters in accounting for events, people and places. Figuring out how to reconcile this contradiction, using photography, is the essential story of Santu Mofokeng’s work.

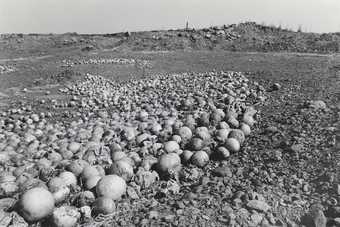

Santu Mofokeng, Fevriary 3 Mass-Grave, Mozambique 2002, printed 2011, from the series Landscape and Memory 1997–2011, gelatin silver print on paper, 38 x 58 cm

© Santu Mofokeng Foundation, image courtesy Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg

Three photographs from Santu Mofokeng’s series Landscape and Memory 1997–2011, three photographs from his series Climate Change 2007, and five photographs from his series Billboards 1991–2009, were purchased with funds provided by the Africa Acquisitions Committee in 2017.

Sean O’Toole is a journalist and editor based in Cape Town, South Africa.