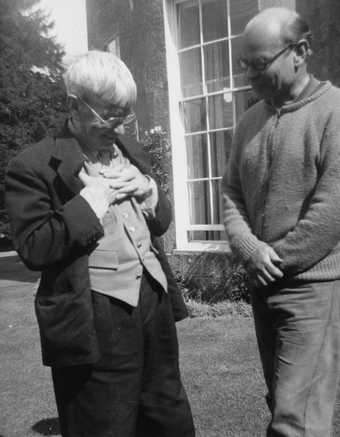

Father and son: William with John Rothenstein, Hampstead, 1903

GREGOR MUIR John Rothenstein came from a highly artistic background. His father was William Rothenstein, his uncle Albert Rutherston and his younger brother Michael Rothenstein, all practicing artists. Did this make John more sensitive to the needs of artists?

ADRIAN CLARK Yes. Growing up surrounded by art and artists, he learned what they were trying to do. This meant that when he started writing about artists, he was extremely perceptive, especially in the case of the artists he knew well, like Stanley Spencer, Wyndham Lewis and Edward Burra.

GM What challenges did Rothenstein face when he started work at the Tate Gallery in 1938?

AC The Tate in 1938 was in a mess. His predecessor had been a drunk; there was no Government grant, and therefore little money to buy anything. The Gallery was controlled by the National Gallery and its main funding source for acquisitions of new British art was from the Chantry Bequest, which the Royal Academy controlled. He also had to deal with the onset of the Second World War and the restoration of the building after extensive bombing.

Against this background, and a conservative body of Trustees, John was expected to cover the whole history of British art, all modern sculpture and all modern international art. It was an impossible challenge. The later split into Tate Britain and Tate Modern belatedly recognised this.

Stanley Spencer with John Rothenstein, Newington, 1956

GM To what extent did he succeed or fail in grappling with these challenges?

AC After getting the Gallery back on its feet after the war, he regularised its relationship with the RA and the National Gallery. He formed excellent relationships with the Contemporary Art Society, which produced lots of donations for the Tate, and with the Arts Council, which sponsored most of the Tate’s impressive series of exhibitions. He filled all the gaps in the British collection and took every opportunity to build up the foreign collection – not easy with minimal funds. Having worked in America, making many connections with curators there, he promoted the Tate showing modern American art in seminal exhibitions in the 1950s.

His failures were partly due to his own shortcomings as a manager. He got into a terrible muddle administering the trust funds given to the Tate by the National Gallery and foolishly hired a South African curator called Le Roux Smith Le Roux, who did his best to sack him. John also had the misfortune to incur the hostility of a group of art historians who thought he should be concentrating on acquiring what was then termed modern foreign art.

GM Rothenstein is remembered for the ‘Tate Affair’ between 1952 and 1954, having punched historian and collector Douglas Cooper...

AC The great, but very bad-tempered, art historian Douglas Cooper took against many people, including John. He organised a campaign of attacks on John’s directorship through the press, which went on for a couple of years. He was backed in this by information supplied from inside the Tate by Le Roux. Questions were asked in Parliament about John’s fitness to continue and for a while his career was hanging by a thread. Relief only came when Cooper taunted John at a party and John punched him in the face. The Trustees realised that Cooper had gone too far and backed John to continue.

Henry Moore with John Rothenstein, 1979

GM By the time Rothenstein resigned in 1964 he’d been in charge for 26 years – longer than any other Director of Tate with the exception of Sir Nicholas Serota. Was John Rothenstein a remarkable survivor?

AC He was, because he was very stubborn and determined to resist what he saw as unfair criticism, but the long years of conflict took their toll. Although the trustees backed him, they left him more as a figurehead during his last 10 years before eventually forcing him to resign. It’s quite possible he might have found it easier to leave on his own terms a little earlier.

Gregor Muir is Director of Collection, International Art, Tate.

Adrian Clark is the author of Fighting on All Fronts: John Rothenstein in the Art World, published by Unicorn Publishing Group.