Among the many riches of the archive at Tate is the menu and seating plan for the farewell dinner of Walter Gropius (1883–1969) at the Trocadero, Piccadilly on 9 March 1937. He was leaving England to take up a post at Harvard Graduate School of Design. The menu’s design is by Gropius’s one-time Bauhaus colleague, the great experimenter László Moholy-Nagy. The guest list is a surprisingly eclectic mix of London’s artistic and intellectual life, a gathering of avant-garde artists, architects and critics, and writers, professors and left-leaning politicians, with attendees ranging from Herbert Read to H.G. Wells. Toasts were led by the eminent biologist Dr Julian Huxley.

Gropius had arrived at Victoria Station only three years earlier, in October 1934, as a refugee from a Nazi Germany increasingly hostile to the art he had espoused. The Bauhaus, the experimental art school founded by Gropius in 1919, had been forced to close in 1933. Although he was not Jewish, Gropius, the proselytising modernist, found himself politically ostracised and his architectural commissions dried up. Along with his wife Ise he made a rushed escape from Germany via a theatre conference in Rome.

Gropius came to London speaking English very badly. At that time the Bauhaus and its reputation was known only to a few enthusiasts, yet only three years later he was being lauded in the capital. How had Gropius found himself a role in such a relatively short time?

Marcel Breuer, Ise Gropius and Walter Gropius celebrating the first anniversary of the Isokon Flats on the building's rooftop, Lawn Road, Belsize Park, London, 1935

Pritchard Papers, University of East Anglia, photo: A.V. (Albert Victor) Swaebe

It had much to do with his London milieu and the friends and contacts he made. Gropius came to live in Hampstead, then a centre of radical thinking and left-wing ideology. In the 1930s several thousand German-speaking refugees were residents in Hampstead, the most famous among them (after Gropius’s time there) being Sigmund Freud.

The critic J.M. Richards vividly remembered the ‘babel of tongues’ in the lift to the underground at Belsize Park, as well as the ‘eminent names from the art manuals’, the British abstract artists who formed a Hampstead enclave, and the ‘nest of gentle artists’ as defined by Herbert Read. In Hampstead, Gropius became a friend and neighbour of Henry Moore, whom he considered the best of English artists. He was also in close contact with Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and with Read himself, his great support and champion during his English exile. Read shared Gropius’s belief in art as the central necessity in life, and both insisted that artistic understanding began with the creative education of the child.

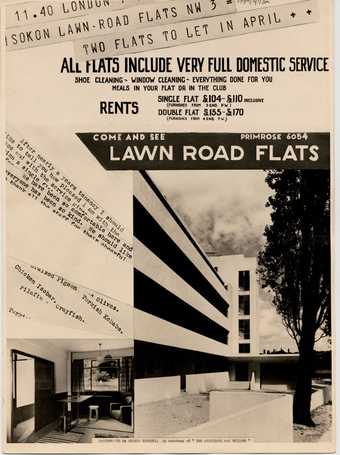

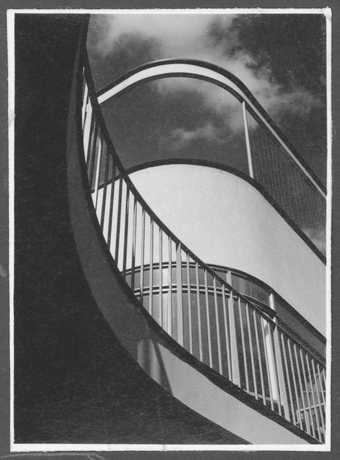

Gropius and Ise were lucky in being offered accommodation in the newly finished Lawn Road Flats in Belsize Park, one of very few wholeheartedly modernist buildings in the London of that time. Lawn Road, also known as the Isokon Flats (on account of its isometric unit construction), was an experimental block of service flats built by one of England’s rare modernist enthusiasts, Jack Pritchard (who earlier on had visited the Bauhaus), together with his psychotherapist wife Molly.

The building, designed by Molly Pritchard’s lover, the architect Wells Coates, was a statement of unmistakeable progressiveness constructed in monolithic reinforced concrete and rendered dazzlingly white. Agatha Christie, a later resident, described the building as a giant ocean liner beached along the street. Richards saw it as a concept that improved on those of Le Corbusier, coming closer to realising a ‘machine à habiter’ (a machine for living in) than Le Corbusier himself. For Gropius, Lawn Road Flats was as near as he could get to an English home from home.

Jack and Molly Pritchard were endlessly hospitable. Lawn Road Flats drew residents from many different spheres. A brochure advertised their clients as being ‘Artists, Authors, Soldiers and Economists, Archaeologists and Egyptologists’. Besides the Gropiuses, other residents in 1934 included the American economist Philip Sargent Florence, the painter and critic Adrian Stokes, and the writer Nicholas Monsarrat – later celebrated author of The Cruel Sea. The following year saw the arrival of two former Bauhaus Masters, Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy. Julian Huxley himself was a Lawn Road Flats habitué, as was J.D. Bernal, the pioneer of X-ray crystallography. It was largely due to the Pritchards’ enormous range of contacts and their generosity of spirit that the Gropiuses made such wide-reaching and enduring London friendships.

The indefatigable Jack Pritchard had plans for Walter Gropius to be involved in a succession of new Isokon projects: a block of flats in Manchester, a block of flats in Birmingham and, most ambitiously, a luxury development of 69 flats on St Leonard’s Hill on the edge of Windsor Great Park. King George V himself had given his permission for this modernist building overlooking Windsor Castle. To Gropius’s chagrin all of these schemes foundered.

View of Levy House at 66 Old Church Street, Chelsea, London, designed by Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry, 1935–6

© DACS 2018, photo: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

The few architectural commissions carried out by Gropius while he was in England reached him through the left-wing cultural contacts he had made. The most spectacular of these was the house in Old Church Street in Chelsea designed for Benn Levy, the playwright and scriptwriter for the movies, and his wife the actress Constance Cummings. They had bought the site jointly with close friends who had commissioned their own house from another German emigré architect Eric Mendelsohn, working in partnership with Serge Chermayeff. The pair of buildings brought a sudden convergence of European modern style to architecturally staid 1930s

Chelsea. The Levys stayed staunchly progressive in their outlook, Levy becoming a post-war Labour MP while collecting and commissioning modern art.

Gropius’s most impressive legacy in England is undoubtedly Impington Village College, designed with his London architectural partner Maxwell Fry and completed by Fry after Gropius’s departure. Impington, too, had come about through the benevolent aegis of Jack Pritchard, a friend of Henry Morris, the recently appointed secretary to the Cambridgeshire Education Committee. Pritchard brought Gropius and Morris together, and the result was ‘orgasm!’, as he characteristically described it. Morris’s ambitions lay in the development of village colleges – central community buildings that provided local education from early childhood to the grave, with an emphasis on the creative. The functional beauty and clarity of Impington was to be influential in establishing the character of English school architecture after the war.

View of the classroom wing at Impington Village College, Cambridgeshire, designed by Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry, 1938–9

© DACS 2018, photo: Dell & Wainwright / RIBA Collections

After a year in England things began improving. Gropius’s English was less hesitant and he grew more confident in public speaking. In 1935 Faber and Faber published Gropius’s book, The New Architecture and the Bauhaus, outlining the ideas and structure of the school and explaining his belief that new materials and technologies opened out fresh opportunities in living human life. Nikolaus Pevsner, a younger German emigré who hero-worshipped Gropius, was already planning Pioneers of Modern Design: From William Morris to Walter Gropius.

From 1936 Gropius was involved in the new progressive publication Circle: International Survey of Constructivist Art, which amounted to a manifesto for the modern, and included contributions from artists, architects, scientists, writers and performers. Gropius himself contributed an essay, ‘Art Education and the State’, arguing strongly for the necessity of making art obligatory in all schools.

He gathered new supporters, most notable of whom was Peter Norton, a remarkable woman who co-founded the London Gallery in Cork Street. Norton’s fascinating archive, now at Tate, shows how she exhibited the work of painters, sculptors and designers mixed informally together in a pioneering spirit. ‘Sales are of course important but they will not be the first consideration’, her opening brochure endearingly maintained. There was a special emphasis on German art and Gropius was on Norton’s advisory council, the start of a long friendship between Peter and the Gropiuses that endured for life.

In June 1936 Gropius applied – successfully – to the Aliens Department requesting permission to stay in England permanently. However, by November he had accepted an invitation from Harvard to become chair of the Department of Architecture in the Graduate School of Design. Why did he decide to leave England at this juncture, just as his ideas were gathering acceptance? Should Gropius have stuck it out? Probably not. Too much was stacked against him. A residue of anti-German feeling, with bitter memories of the First World War, endured in Britain.

In spite of Peter Norton’s efforts, modern mid-European art remained a mystery in a culture still ruled by the predominantly French aesthetic promoted by Roger Fry and the Bloomsbury Group. Anthony Blunt rightly gave the reason

for the English dislike of modernist buildings as being ‘because they are not homey’. In his 1928 satiric novel Decline and Fall Evelyn Waugh creates an unforgettable comic character, Professor Otto Silenus, the austere dogmatic German modern architect. Gropius became associated with Silenus in many English minds.

Most seriously for Gropius, for whom building was his lifeblood, was the paucity of architectural commissions in a country where, in the years of the depression, work was scarce for British architects themselves.

Gropius left England and his friends there with lingering fondness and regret. His Trocadero farewell dinner was emotional. Publicly he was always tactful in his remembrances of those London years. But I suspect that fundamentally Gropius’s later views remained very much the same as his early impressions, revealed in a confidential letter to a German architectural colleague, that England was an ‘a-cultural country’ notable for its ‘general cluelessness and lack of artistic ability’.

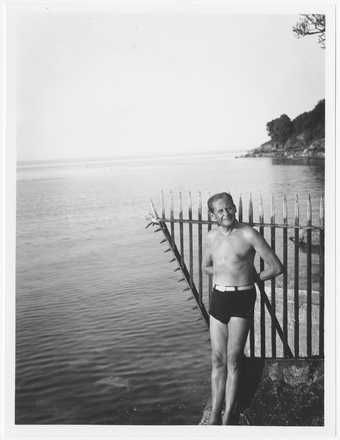

Walter Gropius by the sea during a trip to Totnes, Devon, 1933

© DACS 2018, photo: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

The Bauhaus and Britain, Tate Britain, 17 June – 17 November, curated by Rachel Rose Smith, Assistant Curator, Modern British Art, Tate Britain, with Elizabeth Darling, Reader in Architectural History, Oxford Brookes University, Robert Sutton, Teaching Fellow in the History of 20th Century Art, University of Leicester, and Michael White, Professor of History of Art, University of York. 2019 marks the centenary of the founding of the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany.

Fiona MacCarthy is a biographer and cultural historian. Her latest book, Walter Gropius: Visionary Founder of the Bauhaus, is published by Faber & Faber.