Takis with a selection of his Signals sculptures for the exhibition White Signals at Indica Gallery, London, 1966, photographed by Clay Perry

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019, photo © Clay Perry, England & Co, London

For me, the work of Takis sits somewhere between that of fellow artists Alexander Calder and Jean Tinguely, a place where the mechanics of electromagnetism meet kinetic elegance and aesthetic form.

What appeals to me about his art is how the breadth of his investigation seamlessly crosses over many disciplines, such as music, science, sculpture and performance, through a very defined medium: energy. Through his research and passion for science he recognised the magic in the potential for the electromagnetic to be transformed into an aesthetic language that could go beyond scientific phenomena.

His proclamation of being an ‘intuitive scientist’ is a curious thing. How does the idea of being ‘experimental’ differ when applied to scientific endeavour as opposed to artistic practice? A scientist tends to experiment with a clear intent: to qualify or disqualify a theory. An artist like Takis, however, experiments with no fixed idea of what the outcome might be – a sense you get in his ‘telemagnetic’ works from the 1960s and 1970s. Both approaches are about discovery, but where the scientist is, for the most part, working out the mechanisms behind nature, the artist is trying to find out what nature is capable of.

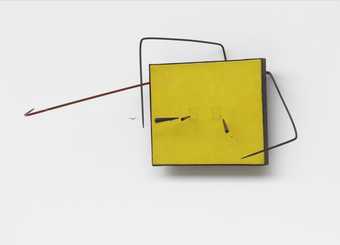

Takis, Telepainting 1959, acrylic paint on canvas, magnets, nylon thread and steel, 28 × 61 × 35 cm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019, collection of Liliane Lijn, photo: Tate / Andrew Dunkley and Mark Heathcote

So the artist may set out with a goal of sorts, but often the incidental phenomenon that emerges is more interesting to follow and embrace. For the scientist, the incidental observations are usually a distraction, and perhaps another observation to explain later. In this sense, Takis may be describing his liberty to follow his instincts – proof is not just a prerequisite. And with this comes an extraordinary body of work, distinct from other artists of his generation.

What is it about electricity, magnetism and kinetic energy that is so interesting, and must have inspired Takis? (It took me many years of working with electrical energy to identify that it was indeed my medium as an artist.) There is a sense of ‘liveness’ that fascinates me. We often take for granted that electricity is a naturally occurring phenomenon, because we see only powered, manmade artefacts and not electricity itself. Because of this, we assume that we’re somehow in control of electricity, which is not entirely true.

We do a good job of harnessing and working with it, but, as with anything in nature, electricity is ultimately chaotic: fluctuations are always found when measuring electrical currents. When confronted with this – whether a thing is animated, or whether an object appears to be defying gravity – we feel a sense of energy.

Takis, Magnetic Ballet 1961 (shown in motion), cork, electromagnet, magnet, nylon thread, steel and wood, 45 × 40 × 40 cm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019, photos: Tate / Andrew Dunkley and Mark Heathcote

Takis, Musical Sphere 1985, aluminium, iron, metal string, metal wire, paint and polyester, 160 × 100 × 114 cm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019, Takis Foundation, photo: Hlias Nak

I believe this sense is not just an intellectual one, but also a physiological one. The energy resonates in parts of our bodies without us even being conscious of it. In contrast to the more commonly found static sculpture, by seeing objects in motion or floating due to electricity and magnetism – such as in Takis’s Magnetic Ballet 1961 – one gets the sense of a live experience, much like the difference between attending a gig and listening to a recording.

This gives Takis’s work a sense of performance: the work performs for you, which, in turn, also gives the impression that the work has an autonomous life of its own. This is always a curious and engaging thing. In most instances, this type of approach can venture into the territory of gimmick. Takis, however, has always been an artist who moves from one stage to the next with nuanced ease. He is truly a progressive artist.

Haroon Mirza’s stone circle 2018, black marble boulders with integrated LEDs and speakers that produce patterns of electronic sound and light from energy generated by solar panels, in the desert grasslands east of Marfa, Texas

© Haroon Mirza, courtesy Ballroom Marfa and Lisson Gallery, photo: Jennifer Boomer

Haroon Mirza is an artist who lives and works in London. He has forthcoming solo exhibitions at Sifang Art Museum, Nanjing, China, 8 June 2019 – February 2020; Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, from September 2019; and John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, from October 2019.