Sista Pratesi on Bridget Riley’s Blaze 1964

When I saw this painting for the first time something permanent changed in me. It brought on a sense of “feel the fear and do it anyway”.

My stepfather was a hypnotherapist. He tried to get people to lose weight to become successful, to find a girl, to be somebody. His book, How to Get What You Want, should have been a best-seller. I never read it. I never looked him in the eyes for fear of being hypnotised and falling under a Svengali-like spell (a fear fuelled by films such as The Stepford Wives ), or being fooled in a Truman Show -meets -Vertigo -spawns-The Matrix kind of way.

My twenties were spent avoiding mirrors and hallucinogenic drugs. By the time Bridget Riley’s show opened at Tate Britain, I knew I was ready for some visual action.

I go to the show on my own, reasoning that if I come out as someone else, I can just disappear. I’m nervous when I come across Blaze. I don’t look at it head on – just keep it at the edges of my eyes, as if I’m not interested, have seen it all before. When I’m ready I turn and look into the centre of the painting and I let myself go. It starts with an adjustment of the eyes, and then a shifting, pulsating feeling envelops me. A floating sensation begins in my body, so overwhelming that I lose myself and cannot tell where this feeling begins and I end. The experience makes me become aware of the rhythm in everything I see, and I start to search for it in all paintings and all things.

Blaze was presented to Tate in 1975.

Tomma Abts on Gwen John’s Chloë Boughton-Leigh 1904–8

Gwen John

Chloë Boughton-Leigh

(1904–8)

Tate

I first encountered the work of Gwen John in the form of a postcard depicting one of her paintings of nuns. It resided on a dusty shelf in my bathroom for a couple of years, and though it was just a small reproduction, it radiated intensity. Coming from Germany, I hadn’t heard of Gwen John at all.

The recent exhibition at Tate Britain was the first time I had seen the originals of her beautiful paintings. While the later paintings tend to dissolve into mysterious fields of drily applied colour, you can already see a particular touch in this earlier portrait of a friend (she only ever painted women).

I like its colours, the greys and olives, and how the sitter’s dreamy gaze is emphasised by the slightly dishevelled placement of her accessories. The space around the figure is dense and crowded even more by the painting in the background, which seems to be hanging from the top edge of the canvas. Though the composition is simple, it feels very concentrated..

I found this quote in one of Gwen John’s letters to a fellow artist, and its sense of readiness for adventure reminded me of painting:

“I bathe in a natural bath, three miles away, the rocks are treacherous there, and the sea unfathomable. My bath is so deep I cannot dive to the bottom, and I can swim in it - but there is no delicious danger about it, so yesterday I sat on the edge of the rock to see what would happen – and a great wave came and rolled me over and over - which was humiliating and very painful, and then it washed me out to sea – and that was terrifying – but I was washed up again. Today the sky is low, everything is grey and covered in mist – it is a good day to paint.”

Chloë Boughton-Leigh was purchased in 1925.

Gerald Davies on J.M.W. Turner’s Inside Yordas Cave, Kingsdale 1816

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Inside Yordas Cave, Kingsdale

(1816)

Tate

As an artist I’m used to my curiosity leading me down blind alleys and into dark corners. With a guide I have swum through flooded passages towing a sketchbook in a sealed container. I have abseiled 180 feet (55 metres) down the open shaft of Alum Pot in Yorkshire, into a lost world of hanging ferns and rocks. Each time I stop to draw I am bewildered by feeling partially blind and overwhelmed by senses that, as a visual artist, I had relegated long ago.

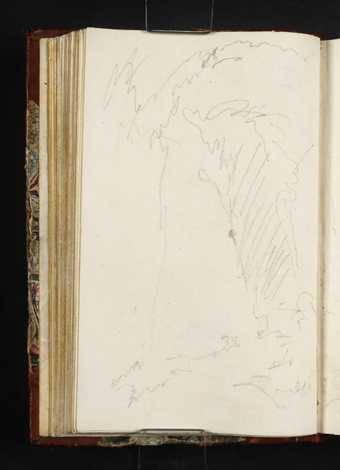

I was reminded of these emotions when I came across a sketch by Turner called Inside Yordas Cave. The cave is in a valley behind my house in the Yorkshire Dales. It is a peculiar drawing. Its wild and jagged lines are unlike Turner’s customary measured precision. It looks like a section from a seismograph. When Turner visited Yordas it was a show cave on the Victorian tourist trail, complete with local guides carrying candles and torches. Having now drawn in Yordas I know that even modern headtorches provide only sufficient light to gather broad impressions, but not enough to uphold a clear view.

Although my cave drawings attempt to depict what’s actually there, they are equally informed by the shapes I have to make with my body, the complexity and texture of rock formations, the taste of fellwater, numbing coldness, sounds of cascades and drips, smells of earth and ionised air and a fear of the dark. I like to think that Turner too, quite unintentionally, drew what it felt like to be there. I’m not claiming him as the first Expressionist, but I think, like mine, his hand was driven as much by disorientation and shivers of cold and fear as by what he saw.

Marcel Dzama on William Blake’s The Wood of the Self-Murderers: The Harpies and the Suicides 1824–7

William Blake

The Wood of the Self-Murderers: The Harpies and the Suicides

(1824–7)

Tate

like the softness of the watercolour and the lusciousness of the trees in this image. It contrasts with the tone of the story. Blake has taken a scene from Dante’s Inferno - the Second Ring of the Seventh Circle of Hell – in which Dante comes across the souls of those who committed suicide and have to endure eternity in the form of trees. The moving, breathing trees are prisoners rooted to the ground. The nesting harpies – birds with human heads – that feed on their leaves are the gatekeepers to the trees.

If you look closely, you can see how one of the trees bleeds when Dante pulls off a branch. This tree carries the spirit of Pietro dell Vigne, a man who died by dashing out his own brains. Blake’s interpretation of this story is my favourite, and has influenced the way I render my characters. You can often see tree men in my work.