Hamad Butt’s Transmission at Milch Gallery, London, 1990

© Jamal Butt

‘Before conceptual understanding there is a state of perceptual mystery’

– Hamad Butt

Hamad Butt was born in Lahore, Pakistan, in 1962, and moved with his family to Britain two years later. He was brought up and educated in London, and was initially drawn to the study of science, taking biology, chemistry and maths alongside art for his A-Levels. At the same time, he began enrolling in courses in drawing and printmaking in schools such as Central Saint Martins, before taking a BA in Fine Art at Goldsmiths’ College between 1987 and 1990. There, he studied with a new generation of British artists, including Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Angus Fairhurst. Under the influence of tutors such as the conceptual artist Michael Craig-Martin, Goldsmiths in the late 1980s had become a breeding ground for new approaches to art by moving away from dividing an artist’s education into separate phases of learning in different media forms: painting, sculpture, printing, and so on. Students instead worked across different media and disciplines, and something of this interdisciplinary ethos encouraged Butt to use art to explore his earlier interest in science.

Looking at photographs of the two major installations Butt produced in his short life – Transmission 1990 and Familiars 1992 – you could be forgiven for thinking you were looking at the laboratory equipment of an experimental chemist, or prototypes from the studio of a strange, cryptic engineer. Transmission consisted of a ring of glass books lying on the floor in a darkened gallery, each illuminated by a blue neon spine and watched over by a single glass vitrine in which flies hatched from eggs, consumed paper drenched in sugar, and then died. Familiars was made up of three glass and metal sculptures, each containing a different halogen element: there was chlorine in transparent spheres, evoking a chemist’s mixing flasks; iodine in glass tubes shot through with glowing wire; and bromine in the transparent tips of three curving poles that resembled a massive set of tweezers.

Hamad Butt’s Familiars Part 2 – Hypostasis at Milch Gallery, London, 1994

© Jamal Butt

Yet science, for Butt, wasn’t what it normally seems: a way of producing knowledge based on experimentation, observation and rational investigation. In a note scribbled on the many pages of photocopies and sketches left behind in his archive, he wrote, as if outlining an intention: ‘The use of “science” as a metaphor for clear thinking to sublimate (and thus purify) the thoughts that originate in distraction / irrational / fear and become apprehended / rational / contained.’

Science, as a particular way of understanding the world, is the outcome of a prior, embodied reaction to that world: confusion, uncertainty, terror. Not only that: it enables us to forget these reactions and encourages us to think that the world, and our bodies, are something we can control through our manipulation of physics, chemistry and biology.

Butt’s installations are attempts to make us experience what he called apprehensions: ‘the seizure and arresting of perceptions (from the senses or from the intellect) that are anticipated by fear to the point of understanding’. Apprehension is what happens when the world grabs hold of us: ‘The etymological basis to “lay hold of ” ... literally inscribes the “gripping” (as with both “grasping and “groping” we return to the “handful”) that is the mutuality of fear’. As the saying goes: I was gripped by fear. Flinches, shudders, recoiling, tremors: all these instinctive reactions are signs that a dangerous world is trying to get at us. The apprehension of fear, then, is the hidden theme of these seemingly clinical installations. Like Nietzsche, Butt believed that ‘fear ... is man’s fundamental sensation; everything is explained by fear’. Yet for Butt, paradoxically, we have become too afraid of our fear: we have to relearn to feel those original apprehensions in order to truly understand our relationship to the world. We need to overcome our fear of being touched by the world in order to touch it back.

A page from one of Hamad Butt’s notebooks in Tate Archive, featuring a sketch of the sympathetic nervous system and notes reading: ‘Flight or Fight? / Fight or Flight? / Apprehension – Fright / Apprehended – Fight / Apprehensive – Flight’

© Jamal Butt. Photo © Tate

That Hamad Butt had much to fear at the time of making these works is one reason why they remain so compelling today. Britain in the 1980s was a country whose Prime Minister was herself adept at sublimating fear for her own ends. In 1978 Margaret Thatcher declared that ‘people really are rather afraid that this country might be swamped by people with a different culture’; that is to say, by people like Butt and his family. As a gay man growing up in the 1980s, another kind of fear was inescapable: the fear of contracting HIV, which was untreatable until the advent of antiretroviral therapy in the mid-1990s. That meant the loss of a whole generation of gay and queer artists: Félix González-Torres, Derek Jarman, Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar and many, tragically, more. From this one fear grew others: a terror of sex and intimacy; a dread of disease and illness; and suspicion towards the scientific and medical establishment whose delay in devoting resources to the treatment of HIV/AIDS led to the loss of tens of thousands of lives, among those Butt, who died of an AIDS-related illness in 1994.

These fears seep into Transmission in oblique and coded ways. While a student at Goldsmiths, Butt wrote a long essay on the history of gay pin-up magazines, and the way they shaped gay male desires. He saw them dominated by two types of bodies: the muscular oiled body of the athlete, and the slender body of the young man. Both embody a kind of perfection: the first of strength, the second of innocence. Both appear as untouchable, or untouched: the first through its chiselled perfection, the second in its youthful virginity. This is what makes these bodies, for gay men, so desirable. While everyone wants to touch what they cannot have, gay men also at the same time desire to become these same perfectly untouchable bodies. And so, there is a fear of sexuality present in the very images that define one kind of gay male sexual desire. What you want is to be someone untouched by your own kind of want – so that desire, by implication, becomes something shameful. This fear, Butt concluded, drawing from Freud, Lacan, and feminist psychoanalytic critics, was a form of ‘castration anxiety’: we worry that the thing we desire will damage us, but, perversely, this causes us to cling to it even more.

A photograph of a Penguin Books edition of John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (1951), from Hamad Butt’s archive at Tate

© Jamal Butt. Photo © Tate

For Butt, this fear of sexuality was hardly unique to gay men. He also studied the iconography of popular science-fiction books and films such as Night of the Living Dead (1968) or Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), seeing in their representation of dangerous alien life forms that threaten the white suburban nuclear family a manifestation of what he called the ‘fearful sexuality of the 50s or 80s’. It was from the world of science fiction that he landed on the cryptic image at the centre of his first installation, Transmission: the Triffid, the horrifying titular creature from John Wyndham’s 1951 novel, The Day of the Triffids. The Triffid is a mobile, long-stemmed, carnivorous plant that slashes out a venomous sting: what Butt called in a note a ‘dangerous, ejaculating (contaminating) pudenda’. This terrifying symbol of male sexuality – or rather, a symbolising of a male sexuality that is terrifying – is a ‘mutated, mutable, substance [that] kills us’. In another notebook, he listed everything the Triffid symbolised: ‘science fiction / Cold War / Fear / Disease (AIDS)’.

An image of a Triffid was inscribed on each of the glass books arranged in a circle to make up the central sculpture in Transmission. The books were also illuminated by ultraviolet light, intentionally making the books difficult to look at in the darkened gallery. Butt requested that goggles be provided alongside the work, to literalise the fact that the viewer was being asked to look up and search for knowledge that would blind them. The clinical, antiseptic, technological material of the installation disguised at its heart a whole cluster of fears: of sexuality in general, and phallic sexuality in particular; of the gay man as a threat to society and of AIDS as a threat to gay men. That this knowledge is contained in a book that is unreadable to the naked eye suggests that these are fears we apprehend – that grip us – but that we don’t want to know about. And overlooking this cycle of fear and repression is another cycle: the vitrine of flies that hatch, consume paper soaked in sugar, and then die: a mockery of the idea that knowledge will set us free, unless we first grasp the fears that grasp us.

A detail of Hamad Butt’s Familiars Part 3 – Cradle at Milch Gallery, London, 1994

© Jamal Butt

Transmission was first displayed as Butt’s final year project at Goldsmiths, and then at the short-lived Milch Gallery in Bloomsbury. Milch Gallery was one of the many fleeting exhibition spaces opening and closing as part of the great ferment in the London art world in the late 1980s, an era that would be later codified as that of the birth of the Young British Artists. Indeed, shortly after Butt’s Transmission, Milch exhibited Damien Hirst’s In And Out Of Love 1991, which was in part strikingly similar to Butt’s: butterfly pupae, attached to a canvas, hatched, lived and died in the gallery.

Looking back at British art of the 1990s, the writer Isabel Waidner has recently written that the attention claimed and given to the YBAs arguably ‘contributed to the marginalisation of a generation of 1980s Black British artists – such as John Akomfrah, Sonia Boyce, Chila Kumari Burman, Lubaina Himid, Isaac Julien, Keith Piper and Ingrid Pollard – whose work centred politics and race (then “identity”), or the art that developed in relation to the AIDS crisis.’ As a gay artist of colour whose work was an intellectually idiosyncratic yet direct response to the AIDS crisis on a personal and collective level, Butt is exactly the kind of artist that Waidner rightly pinpoints as having been comparatively forgotten in the history of British art. Now that the achievements of these artists are being rightfully recognised through retrospectives and awards, the moment is also right for a reappraisal of Butt’s work so we can better understand what it means to us in the present.

A compliment slip sent to Hamad Butt from Pacegrove Limited regarding the delivery of a sample of iodine, from Hamad Butt’s archive at Tate

© Jamal Butt. Photo © Tate

Butt’s next installation, Familiars, asks us to think hard about what we want from art that might ‘represent’ the AIDS crisis, or art that might centre identity – whether that of a gay man, a person of colour, a Muslim, or all of these categories at the same time. Familiars was an experiment aimed at forcing us to apprehend our fears. And an experiment it was: to develop the installation, Butt corresponded with chemists and engineers from universities across Britain in order to carefully construct glass equipment in which three hazardous substances – chlorine, iodine and bromine – could not only be preserved in a gallery, but, in the case of the iodine, could also be heated by electric currents and sublimate, or change state, from solid into gas and back again. These gases really are a danger to human health. The chlorine gas, if inhaled, dissolves the lungs from within. Bromine can cause the body to break out into blisters and lesions. Yet iodine is a disinfectant: it can heal cuts and sores, but only by killing bacteria. Butt played up this danger when the installation was first exhibited at the John Hansard Gallery in Southampton by asking that protective suits and goggles be hung at the entrance. This very danger, ironically, led to the piece disappearing from the art historical record. After Familiars was exhibited at Tate Britain in 1995 as part of the group exhibition Rites of Passage, Butt’s family suggested Tate acquire it for its permanent collection. The curators initially refused over a concern about ‘how to preserve the toxic chemicals’. It was finally acquired in 2014 but has yet to be re-exhibited at Tate.

Familiars wants us to apprehend something that is toxic, but which, at the same time, might also promise us a cure. That this piece, odd as it might seem at first sight, is in part about the complex interaction of fear, desire, medicine and technology that constitutes the impact of HIV/AIDS on sexuality is suggested by the fact that the sculpture containing the bromine is shaped like the end of a Triffid – Butt’s private symbol of a terrifying, toxic, threatening phallus. But if this piece is about the apprehension of fear, it is also about the promise and prospect of transformation. The iodine in the glass capsules changes state. Can the things we fear be transformed into something else? Can our fear itself be transformed?

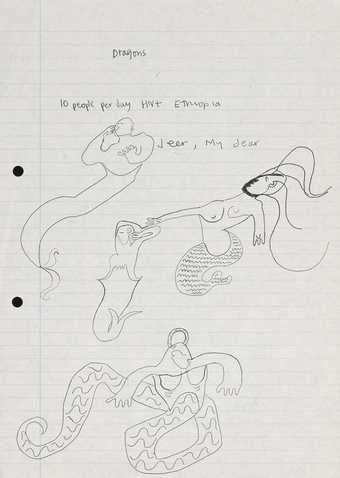

A sheet of paper from Hamad Butt’s archive at Tate, featuring sketches of merpeople and notes reading: ‘Dragons / 10 people per day HIV+ Ethiopia / Jeer, My dear’

© Jamal Butt. Photo © Tate

In the small collection of his notes published after his death in the book also called Familiars (1996), Butt explored some of the reasons why he wanted to create apprehensions of fear, rather than directly ‘represent’ HIV/AIDS in a more literal way – as, for example, in the NAMES Memorial AIDS Quilt, an ongoing work made up of quilt panels representing the life of each person who has died of AIDS in the United States. Alluding to Susan Sontag’s essay ‘Illness as Metaphor’ (1978), he noted all the ways in which the fear of AIDS – its apprehension – had led it to acquire all kinds of metaphorical meanings: it came to signify homosexuality itself as a disease infecting society, and the bodies of those who were HIV positive as a threat that had to be sought out, treated and cured. These were all ways of displacing the primal embodied fear triggered by the virus: as Butt wrote, ‘the fear of AIDS is eluded by the transcription of contamination upon the body of others’. In this perverse sublimation, the ostensible victims of HIV need to be made visible because they are also a threat: ‘let us remember that the threat of the victim is exactly that, in as much as the fear is the threat from a reservoir of victims’. Indeed, Butt also wrote that ‘one of the risks in representing AIDS is the identification [of ] the others of the social order, the others that the presumed healthy community can continue to “scapegoat”’. From this perspective, making the victim visible – as in the AIDS quilt – might be as much a way of remembering them as finding something concrete onto which we project our ambient fear. But this leads us away from our first, instinctive, apprehensions of terror.

Hamad Butt’s Familiars Part 1 – Substance Sublimation Unit at Milch Gallery, London, 1994

© Jamal Butt

At the end of his book Familiars, Butt expressed the position in which these risks left the artist. ‘We cannot respond to this epidemic without fear and confusion, without aching to know why ... We have a politics of representation that is so distinct from the conventional representation of politics seen in so-called political art, since we have an expanding constituency that relies on apprehension to shield the eye.’ AIDS is something we apprehend, before we understand it: it grasps us with fear and confusion. This is something that can’t be shown by straightforward ‘politics of representation’: to display, for example, the faces and bodies of those impacted by the disease. To show the subliminal apprehensions that drive the ongoing fear of people with HIV requires what he called a ‘strategic withdrawal’: the decision to avoid direct forms of self-representation, naming or display, and instead to play with all the embodied reactions of seduction and danger, desire and terror, to draw us in and beyond fear. Or, as Butt concluded: ‘There is the acknowledgement of loss and the numbness of its repetition, which moves us in particular to displace fear with some charming dialogue; an ungraspable sleight of hand.’

To think about Butt’s installations in this way is not to see them as simply or literally autobiographical: the expression of the fears and desires of one particular person. In fact, the decision to make a ‘strategic withdrawal’ from the visual representation of specific individuals and identities results in his work exploring the shared, collective and social apprehensions that grasp us when we are faced with the threat of disease and danger. These are apprehensions that, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, have indeed become shared by all. But these works – in presenting us with books that blind us, or science that threatens us – also make us reflect on the apprehensions that drive us to seek solace in science, knowledge and authority as a consequence of fear. They ask us to think whether doing so uncritically might always be so wise. And they make us apprehend the tangled relationship between fear and desire: how we are afraid of what we want, and how we can become addicted to fear – the fear of the other, the outsider, the victim. As politicians like Thatcher and her descendants have long realised, giving people things to fear is giving us what we want. Butt’s quest for self-revelation was an attempt to explore the hidden apprehensions of fear and desire that grasp us all.

Hamad Butt’s Familiars and Transmission were presented by Jamal Butt in 2015 and 2019 respectively. The archive of Hamad Butt (TGA 201919) was presented by Jamal Butt in 2019. This collection is being catalogued by Darragh O’Donoghue. To discover more about Tate Archive visit tate.org.uk/art/archive.

Kevin Brazil is a writer based between London and Berlin. His new book Whatever Happened To Queer Happiness is published by Influx Press.