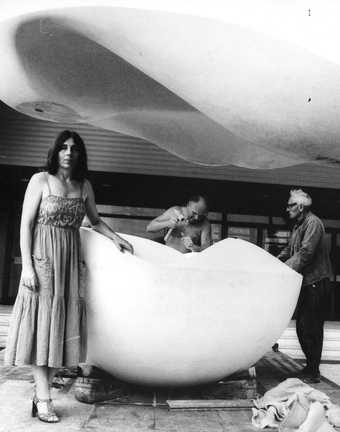

Visitors to Tate’s second Sculpture for the Blind exhibition in 1981 get to grips with Barry Flanagan’s bronze Elephant 1981

© The estate of Barry Flanagan, courtesy Plubronze Ltd. Photo © Tate

Listen to this article

As a blind person, I am always eager to take advantage of the touch tours for people with visual impairments that are offered by many of the world’s art museums. While these programmes vary in quality, I almost always gain some insight into an artist or historical period, carrying away meaningful memories that make me eager to revisit a particular piece or try my hand at artworks elsewhere. However, I know blind and visually impaired people who are not fans of touch tours. Many complain that they feel rushed, conspicuous and generally uncertain about what they’re supposed to derive from the experience. Meanwhile, institutions that don’t already offer haptic and tactile encounters for blind audiences usually tell me that they lack the staff or resources to develop such programmes. Besides, they point out, they receive few requests or queries about such programmes, so where’s the audience? And institutions that already offer a touch tour are unaccustomed to taking unsolicited advice from members of marginalised communities. They are more comfortable assembling focus groups of volunteer stakeholders to evaluate existing programs. This can result in only minor tweaks to what’s already on offer. I have come to believe that the situation will only improve if touch tours cease to be a segregated accommodation for a very small minority of museum visitors and become an experience available to anyone who’s interested. In other words – touch tours for all!

During COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, when museums around the world were shuttered, many augmented their online programming. Art lovers have grown accustomed to online gallery talks and lectures. Now, museums who wish to entice visitors back inside should consider offering haptic art encounters because they are something that cannot be done on a screen. I know many sighted people who express curiosity, even envy, when I describe touch tours I have been privileged to enjoy. It’s clear to me that there are a lot of sighted people who really want to get their hands on art.

Where touch tours for blind people typically fail is that they are designed with a naïve and even reductive understanding of the significance of touch to people who do not see. Too often there is a belief in a perfect one-to-one analogy between touch in the blind and sight in the sighted. The expectation seems to be that simply laying one’s hand on an artwork will transmit an image of it to the blind person’s mind’s eye. It’s as if the point is merely to discern what natural object is depicted: this is a man on a horse, this is the head of a woman. Moreover, many touch tours fail to make a distinction between what I call informational versus aesthetic touch. Scale models, plaster casts, raised-line diagrams and 3D-printed facsimiles can provide information about art historical concepts such as proportion, perspective and composition but do not provide any real interest or pleasure to the touch. The rewards of touching a work of art often have very little to do with what the artwork represents. It has more to do with the tactility of the materials and observations about how the artist manipulated and shaped them. Frequently there are details of the artist’s craft that are not available to the eyes alone.

An effective touch tour embraces the reality that touch changes everything. When touch is brought into a museum context, it alters the fundamentals of both time and space. Museologists have long observed that the average visitor to an art exhibit spends mere seconds in front of each object, and most of that time may be spent reading wall texts and labels. Docent-led tours encourage more prolonged looking but are still timed to consider attention spans and standing fatigue. Touch requires more time. When a touch tour is timed to correspond with a standard gallery talk or tour, many visitors will only get the chance for brief contact. A more meaningful experience requires the time to move the hands over and around the whole object, and to employ different modes of touching. Gliding the fingertips systematically conveys general information about form, while grasping, tapping and pressing reveal aspects of the object’s materiality and sonority.

A museum that wishes to offer touch experiences to all interested visitors need not simply abandon hands-off policies. They could set aside particular galleries and curate specific objects deemed durable enough for touching and that provide aesthetic rewards to the touch. They should also recognise that many people, including many blind and visually impaired people, have little to no experience with this mode of perception. They should therefore train and employ touch docents to provide guidance on how to approach each object on display. These docents might include blind people who can draw on their experiences of touch tours elsewhere. But museums should also elevate the voices of existing employees who are not often consulted in a curatorial context: conservators, but also exhibit installers who already know a lot about the material qualities of artwork. Guards and gallery attendants can advise curators on which objects in the collection already attract illicit touching.

I realise that many will find my advocacy for touch tours for everyone to be unreasonable, even frightening. Change is challenging, but the future of museums depends on attracting new audiences and providing them with novel aesthetic experiences that will make them eager to return. Change of this kind necessitates upheaval, a scrupulous evaluation of existing practices and hierarchies. True inclusion of previously marginalised groups requires abandoning mere accommodation of difference; it means fostering collaboration with different kinds of knowledge and expertise. In other words, touch tours should cease to be understood as a service for blind people and become an aesthetic opportunity for everyone, guided by blind people and others who already know the pleasures and benefits of artistic touch perception.

Tate offers an array of touch tours, audio-described tours, events and artist-led creative workshops for visitors who are blind or partially sighted.

At Tate Britain and Tate Modern, visitors who are blind or partially sighted and their friends can book a touch tour with our Visitor Engagement Assistants, who describe and facilitate the touching of several works from our collection displays. At Tate St Ives, our touch tour guides facilitate the touching and description

of an unprecedented range of Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures at the artist’s studio and garden. Access and comfort are a priority. We provide seating and refreshments, and go at a pace that suits everyone.

To book a touch tour or to subscribe to our mailing list to find out about our regular events, please email ticketing@tate.org.uk or stivesticketing@tate.org.uk. All tours and events are free.

Georgina Kleege is a retired professor of English who lives in New York. Her most recent book More than Meets the Eye: What Blindness Brings to Art is published by Oxford University Press.

Audio narration by Radhika Aggarwal.