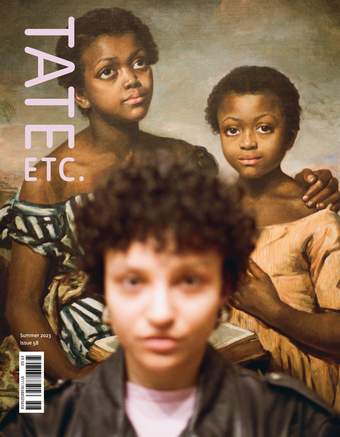

George Stubbs

Horse Frightened by a Lion

(?exhibited 1763)

Tate

The idea that there are at least two moralities – one for humans, and another for non-human animals – is a commonplace. It is a notion grounded in the apparent observation that at issue are simply two different kinds of being. For humans, it is appropriate to speak in terms like dignity, duty, autonomy and respect; for non-human animals, we are more likely to speak in terms of suffering and harm. Individual animals can be culled to save the herd or held captive in a zoo for scientific benefit, but only the monstrous think the same is true of humans. The philosopher Robert Nozick famously suggested that we adopt ‘Utilitarianism for animals, Kantianism for people’, meaning that we should apply a moral calculus that treats animals as interchangeable bearers of happiness and pain but each human as a locus of inalienable rights.

George Stubbs was obsessed with the theme of a lion hunting a horse, painting and engraving it 17 times over 30 years. In the pair of paintings Horse Frightened by a Lion and Horse Devoured by a Lion, exhibited at the Society of Artists in 1763, we see an artist who does not concede the idea that morality for animals is something distinct from human morality. By this I don’t mean that Stubbs was some early animal rights activist; he made many studies of caged lions. But in these two paintings we see the routine encounter between predator and prey treated with the pathos and existential weight normally reserved for human drama. In the first, the lion is all menacing calm, the corners of his mouth lifted in the satisfied knowledge of what is to come. The horse startles with terror; its majestic body is braced for flight, suggesting the possibility of heroic escape. In the second painting, the lion’s face is wild with fleshly pleasure as its teeth sink in. The horse writhes in pain but gives itself over. We should all be lucky to go to our deaths with such dignity.

Stubbs’s paintings raise a question that certain contemporary philosophers have begun to take seriously: whether we, as humans, are morally obliged to stop wild predation. Wild animals who are stalked and eaten suffer greatly. So doesn’t the same moral logic that instructs us to eliminate factory farming imply that we must stop animals from eating each other? Any attempt to instantiate such an idea – like most of our attempts to intervene in the natural world – would likely be disastrous. But what about the question of principle: is wild predation something we would, ideally, if not actually, seek to eliminate?

What do Stubbs’s paintings say? I think they suggest that things are not as simple as the philosophers suppose. Just as human suffering is often wanton and needless, but also sometimes part of what makes life significant – a thing with weight and shape beyond a ledger of pleasure and pain – the same might be true of non-human animals. The encounter with finitude, loss, suffering and death might be part of what it is to be an animal, just as it is part of what it is to be human.

Horse Frightened by a Lion was purchased with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery in 1994. Horse Devoured by a Lion was purchased in 1976.

Amia Srinivasan is Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at All Souls College, University of Oxford.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in