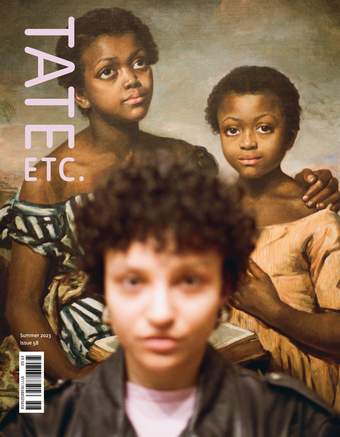

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The Wedding of St George and Princess Sabra

(1857)

Tate

It's a crowded world, and how you navigate it is very much up to you

Elizabeth Siddal's art invites you to look anew. At least, it certainly did me, when a chance encounter with her painting Clerk Saunders 1857 lured me into a PhD. Siddal’s are medievalist artworks to tumble into, to stumble through, faltering and lingering over every strange detail. You’re walking alongside knights, ghosts, watching women, and trees with human haircuts.

In Clerk Saunders, you’re cramped in a murky bedroom with a bright young woman and a dead young man, working a ritual of her devising to set him free from a marriage vow he can no longer keep. It’s a moment reimagined from a reimagination, illustrating a scene from Sir Walter Scott’s take on the medieval ballad ‘Clerk Saunders’, in a style steeped in the religious iconography of 14th-century prayerbooks. And it presses close to you, jostles you against everything in the narrow space: the furnishings; the glowing plant; the alcove of books, crucifix and apple; the rich bed curtains; the prie-dieu (prayer desk) with its painted angel and untouched Book of Hours; the woman and the revenant, and their ritual accoutrements. And then, perhaps, you start to wonder what to do with this plethora of finicky, medievalist detail. With so much going on in such a small space, you’re not tugged in any one particular direction or silently encouraged to look here first! Rather, the choice is emphatically yours.

What possibilities open up in artworks such as this, in which every tiny corner of space has something intriguing? How do all these pieces work together to pluck at the idea of a coherent whole – to make a new whole, coherent in its very incoherence? Why does the man look such an imperfect copy of the painted angel? Why is the woman not at prayer, though the dawn sky and canonical hour and medieval prayerbook dictate that she should be? How much can happen in a painting only marginally bigger than the book it depicts?

Elizabeth Siddal

Clerk Saunders 1857

Watercolour, bodycolour and coloured chalks on paper, laid on a stretcher

28.4 x 18.1 cm

Photo © The Fitzwilliam Museum

This logic and these questions – this interlocking chaos on a taut, small scale – underpin the 1850s medievalist watercolours by Siddal and her future husband Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Rossetti’s art during this period traces a similarly weird and complex path: this is, after all, the man who raged against losing a 16th of an inch of space on a woodblock – ‘I could get a whole city in there!’ You can see the same dense intensity in his watercolour The Tune of the Seven Towers, completed the same year as Clerk Saunders. The subject matter is more mysterious, inferred in scraps from the title. The lady in red is trapped in her chair by a musical instrument, and there is a Castle of the Seven Towers that was used as a prison in medieval Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), though whether Rossetti’s figures are inside it is anyone’s guess.

It’s another cluttered interior, in which patterns and objects and four perturbed-looking people cluster together. There’s no pictorial hierarchy, no vanishing point or significant shaft of light: you can look anywhere you want and your gaze will inevitably have to clamber over several things in the doing, such as the flagpole that seems to pin down the lady’s wrists, or the cushion that squashes her blue-gowned attendant. It’s a crowded world, and how you navigate it is very much up to you.

Siddal and Rossetti developed and experimented with this style together, at the midpoint of a century full of cluttered anxiety. Poet and critic Matthew Arnold fretted in his letters that the past offered ‘a smaller harvest than now, and sooner to be reaped: and therefore to its reaper was left time to stow it more finely and curiously’. To be a Victorian practitioner was to live in ‘damned times’, in which ‘everything is against one’ – to exist cheek by jowl with ‘the height to which knowledge is come, the spread of luxury, our physical enervation, the absence of great natures, the unavoidable contact with millions of small ones, newspapers, cities, light profligate friends, moral desperadoes … our own selves, and the sickening consciousness of our difficulties’. Even with their medieval subjects and settings, the worlds of Clerk Saunders, the Seven Towers and their ilk are steeped in this contemporary crush, a harvest haphazardly stowed.

But I should be clear: this chaos is by no means a bad thing. As I said, it invites new ways of looking, and thrives on the creative curiosity of its viewers. It led me to the process of queer reading, which I understand as an approach that plunges into and thrives on a work’s disruptive impulses. And these artworks are disruptive, certainly by Victorian standards, for all that they speak to the period’s anxieties. They were created in defiant isolation from dominant, state-sponsored artistic norms. Siddal considered getting artistic training from the Government School of Design but chose Rossetti for her tutor instead (she paid him in modelling sessions). He encouraged her to prioritise her creativity, to explore sources dismissed by contemporary standards of excellence, and to work with art’s histories in an idiosyncratic and imaginative way. As a younger man, Rossetti had chafed amid the strict hierarchies, rigid expectations and classical anatomies of teaching principles at the Royal Academy, where he enrolled as a student in 1845; working-class Siddal, much to his delight and envy, had never experienced them. And so the pair delved elsewhere for inspiration: medieval manuscripts, ballads, iconography, plots and people.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The Tune of the Seven Towers

(1857)

Tate

It was a delve in good company. A turn to the medieval had gripped the whole century, including – but not limited to – their Pre-Raphaelite circle. The 19th century saw widespread and vigorous interest in translating, cataloguing, reimagining, and swooning over ideals and remnants of a thousand-year history (c.500–1500). Victorian medievalism was varied; it could be co-opted into state posturing, colonial administration, modern technologies, socialist ideals, academia, queer religiosity, re-enactment, fashion, Dorian Gray’s home furnishings – and, of course, art and literature. Siddal and Rossetti weren’t purists: their watercolours drew on subjects, motifs and influences from material both medievalist and actually medieval.

This creative blurring is apparent in their collaborative work The Quest of the Holy Grail c.1855, a watercolour painted by both artists from a composition devised by Siddal. Sir Galahad – the knight depicted on the quest in question – is the stuff of Arthurian legend, featuring in Sir Thomas Malory’s 15th-century retelling Le Morte Darthur, but the design also draws on fragments from ‘Sir Galahad’ (1834), Alfred Lord Tennyson’s medievalist reworking. Tennyson’s poem describes Galahad encountering (at various stages) a ‘secret shrine’ with ‘silver vessels’ and a ‘shrill bell’, a ‘magic bark’ with ‘no helmsman’ in which he floats ‘till all is dark’, and ‘three angels’ sailing ‘On sleeping wings bearing the Holy Grail’.

Siddal’s composition plaits these motifs into the eerie setting of a flooded church, through which Galahad drifts on his precarious boat. Dismembered parts of old tombs jut up from beneath the water’s surface, crucifixes bar the stone windows, and a bell hangs in a shadowy tower. Galahad, delicately balanced, is jostled even in this remote and lonely place: angels surround his craft, revealing golden cups on either side, drawing him into dialogue once again with a complicated visual landscape. He stares out at relics from the past, in a place and pose that blend medieval iconography with medievalist literature.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Elizabeth Siddal

The Quest of the Holy Grail (c.1855)

Watercolour on paper

Tate/ Rod Tidnam

There’s no neat binary between past and present here, for Galahad or the painting. This medievalism is not cosy nostalgia for a pre-industrial age, nor is it exclusively a passive lens through which to foreground modern concerns. Reshaping the past may speak to the present, but doing so doesn’t leave the past unscathed – a complicated relationship explored in Carolyn Dinshaw’s queer medievalism study How Soon is Now? (2012). In Clerk Saunders, for instance, Siddal’s iconographical workings are disruptive: her characters’ poses and relationships pull the medieval Annunciation to pieces, as I’ve explored in my work elsewhere. Other Victorians may have seen the past and present in a binary – the art writings of John Ruskin (Siddal and Rossetti’s sometime patron) claim that ‘all the pleasure of the mediaeval [sic] was in stability, definiteness, and luminousness’, while modern painters ‘are expected to rejoice in darkness, and triumph in mutability’. But artworks like these trouble such readings. (Ruskin certainly didn’t leave the past unscathed; he loved personally dismembering medieval manuscripts.) Siddal and Rossetti’s medievalist watercolours are certainly luminous, their jewel colours frequently commented upon, but these bright hues illuminate brilliantly unstable scenes, which resist the certainty of a single interpretation.

How? Through the power of the tiny details – all of the tiny details. Pictorial hierarchy be damned: everything in these paintings is important and in conversation, and – though it might overwhelm at first – the longer you look, the more you will find. The artworks’ medieval influences confound modern standards, but their modern sensibilities also shatter medieval meanings. Created by two defiant, disruptive and fiercely imaginative artist-poets, these works wholeheartedly embrace their own vibrant strangeness. And they give us – readers, viewers, critics, and visitors to The Rossettis at Tate Britain – the chance to be Galahad, weaving through fragments of the past in the unstable craft of the present, with two sharp, strange angels offering us yet more details to contemplate.

The Rossettis, Tate Britain, until 24 September. Curated by Carol Jacobi, Curator, British Art 1850–1915, Tate Britain and James Finch, Assistant Curator, 19th Century British Art, Tate Britain. Supported by The Rossettis Exhibition Supporters Circle and Tate Members.

Nat Reeve has just passed their viva for a PhD on ‘Queer Reading Elizabeth Siddal’ at Royal Holloway, University of London. They were the 2020/21 Amy P. Goldman Pre-Raphaelite Fellow at the University of Delaware and Delaware Art Museum. Their queer Neo-Victorian novel Nettleblack was published by Cipher Press in 2022.