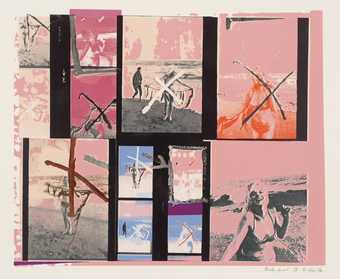

Richard Hamilton

My Marilyn

(1965)

Tate

How to create an image of a woman without making her a slave to beauty? How to bring a woman, who is already an icon, to life? If Marilyn Monroe has taught us anything, it is that public adoration kills as much as it reveres. In the early 1960s, Pauline Boty and Richard Hamilton were transfixed. Boty marched on a CND demonstration alongside Hamilton who was carrying a life-sized cut-out of Monroe, and each of them painted Monroe – or rather painted across one or more of a multitude of existing images – at a similar time.

Hamilton’s My Marilyn came in 1965, a few years after her death in 1962. Boty painted The Only Blonde in the World in 1963, and then painted her several times more, as if the mere act of crafting and recrafting her image would allow Monroe to survive. For both artists, Monroe became the perfect emblem for the revered and disposable fragments ofthe modern world, the detritus whose painstaking collation and restoration was at the core of pop art.

And yet, as these two works make clear, their passion for Monroe assumed very different artistic shapes. Hamilton used a contact sheet of photos by George Barris, taken shortly before her death. This had been marked by Monroe with crosses and ticks to indicate her approval and disapproval (mostly the latter), scoured in places with scissors almost to the point of obliteration – images that Hamilton cuts and pastes, overlays with colour, and blurs. Some critics have seen the work as giving back to Monroe a ‘hint’ of agency. He himself described the work as a testimony to self-destruction, which made ‘her death all the more poignant.’ Either way, he was making his mark over her own.

Pauline BotyThe Only Blonde in the World 1963Oil on canvas122.4 x 153 cm

© Estate of Pauline Boty

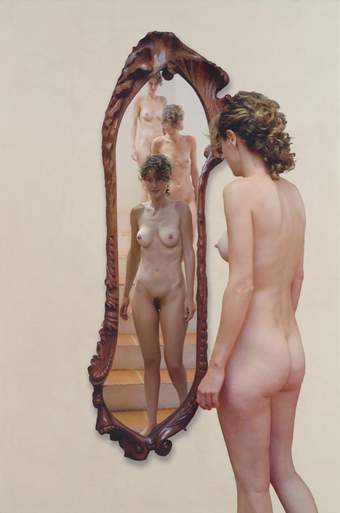

Boty’s painting is based on a still from Some Like It Hot (1959), perhaps Monroe’s most famous film. In stark contrast to Hamilton, and to the original film, which was shot in black and white, she places Monroe inside a profusion of colour and energy: swirls of abstract shapes on the side-strips of the painting, shimmering feathers around Monroe’s body, everything in motion as if she were about to step out of her frame. And yet, Boty’s image is also disturbing. Take a closer look at the red paint marks on Monroe’s legs and they could be gashes, while the dark-grey substance around her upper midriff, where the boa to which she clings falls into shadow, is an indecipherable mess. No viewer can avoid the silent message. A (female) body is being mutilated into art.

If Hamilton’s position is one of ownership (the title ‘My Marilyn’ is surely the giveaway), Boty seems to take the riskier, more intimate, path of identification. She entered body and soul into the women she revered, who included, among many others, the Queen of Sheba, Madame de Pompadour, Collette and Monica Vitti. She performed as Monroe in the annual Royal College of Art revue and became known locally as the ‘Wimbledon Bardot’. One of the ‘terrifying’ things about English Puritanism, she said in an interview, was that young people felt guilty about sex. In her life and work, Boty was asking questions, which, despite the many gains for women, are even more urgent today. What are the possibilities of sexual freedom for women? And at what price?

My Marilyn was presented by Rose and Chris Prater through the Institute of Contemporary Prints in 1975. The Only Blonde in the World was purchased in 1999.

Jacqueline Rose is is co-director of the Birkbeck Institute of the Humanities. Her new book The Plague: Living Death in Our Times will be published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in June.

To read more of our special feature celebrating Tate Britain's rehang, visit www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-58-summer-2023/alex-farquharson-tate-britain-the-state-were-in