A demonstration for Aboriginal land rights marches through Brisbane during the 1982 Commonwealth Games

Photo: Penny Tweedie/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

In 1982, the British Commonwealth Games were staged in my future home base of Brisbane, Australia. At that time, I was working for the New South Wales Aboriginal Legal Service as a field officer. I was involved with a series of protests, attended by Aboriginal people from all around Australia, highlighting the discrimination and injustices suffered by people like me. Of course, the protests became violent and many of us were jailed by police for our attempts to seek an outside voice through the media. We knew the eyes of the world were on us for a brief moment. We called publicly on the governments of the world to boycott Australia as they had South Africa. We strongly believed that South African apartheid had had its origins in the Aboriginal Protection and Restriction of Opium Act of the Queensland Government, which was at least as draconian and equally brutal. We renamed the event the ‘Stolenwealth Games’, drawing attention to the injustice, theft and brutality at the heart of the British Empire’s history of colonisation.

Forty or so years later, the issues for my people have not changed. If anything, they have got worse, after repeated waves of neoliberal erosion of our economic, social and political rights. Neoliberalism was just another form of colonial paternalism with catch phrases like ‘mutual obligation’ and ‘practical reconciliation’ – but it was still about mining rights and taking our land, an aggressive ongoing form of colonialism justified this time around by the Chicago School of Economics.

When I came back to making art full time in the early 2000s, Australia was in the middle of a racist resurgence under the government of Prime Minister John Howard. Ironically, Aboriginal art was booming, but it was the ‘traditional’ and ultimately ‘non-political’ work that was getting the funding, attention and support. I wrote an essay called ‘Bell’s Theorem’ to stake out a position for myself but also to address the connections between the ongoing discrimination and dispossession of my people and the way our art is presented, represented, controlled and distributed in an art world that is primarily white-controlled. The second ‘Bell’s Theorem’ essay, which was written last year, asks what, if anything, has changed in the 20 years since my first essay?

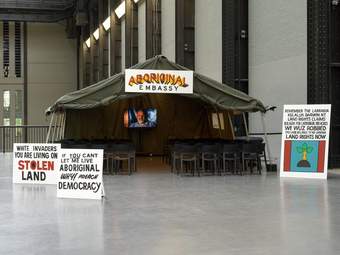

Richard Bell standing in front of his tent Embassy at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, 2014

Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Toni Wilkinson

The question continues to resonate. One thing the essay tries to address is the implications of indigenous art becoming a transnational, international movement that is, and will be – like Aboriginal art in Australia – controlled by white forces. That is, the market will inevitably choose mostly non-political art to promote in its museums and galleries. It’s essentially a form of artwashing, with the art as the botox of capitalism.

That’s why my artwork coming to Tate Modern is so important to me, and for what I want to say for my people. I want them to feel empowered by this. I want to ask difficult questions. I want to find solidarity among peers in both the activist and artistic arenas so we can discuss positively how the situation can be improved. As blackfellas, we cannot get a voice through the media because it is white-controlled. So, for us, art is one of the few spaces left to seek an audience. As far as art spaces go, the Turbine Hall is a pretty decent megaphone.

Perhaps the most important work for these discussions and events will be my sign Pay the Rent (UK), which calculates the amount of rent the UK owes Aboriginal people for its occupation of our lands from 1788 until 1901, when the overtly racist Australian Government was federated (they have their own rent to pay). As Britain has a discussion around reparations for profiteering from slavery, I reckon it’s a good moment to broaden the conversation to ask: ‘What are the costs of the damage done to Indigenous people and their lands all over the world?’ The truth is, the costs of colonialism can never be fully repaid.

We Have

To Share.

Richard Bell: Embassy, Tate Modern, until 18 June. Supported by the Embassy Supporters Circle with additional support from Qantas. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor.