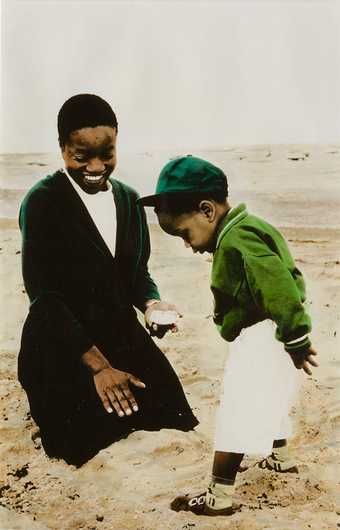

Isaac Julien

Mise en Scène No. 1 (Looking for Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016

Kodak Premier print, Diasec mounted on alumnium

Isaac Julien. Courtesy of the artist

Isaac Julien is an artist I have been studying and have known for almost 40 years. I first heard him speak at a seminar at the University of Sussex when I was doing my MA in Critical Theory, and then a few years later in conversation, possibly with Kobena Mercer, at Warwick Arts Centre. He was so inspiring, but I was too scared, too young, to raise my hand and ask a question. Now, decades on, I have that chance! Ahead of the first major UK exhibition of his work, I sat down with Isaac to talk about history, space and the importance of keeping things open. His aesthetic and political refusal to take a fixed or easy view in the work he creates continues to mark him as one of Britain’s most exciting artists, and, I believe, one of our most valuable guides to thinking, seeing and feeling in a very polarised world.

MARIA BALSHAW Could we start with your early years, and London in the 1960s. Where did you grow up, and what was your childhood like?

ISAAC JULIEN The 1960s are a bit of a blur. I mean, there are certain moments that I remember. Going to Trafalgar Square with my mother, possibly after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and being surrounded by crowds, and feeling upset. Watching someone mowing grass on the Coventry Cross Estate in Bromley-by-Bow, where we lived, and moving towards me and cutting my knees. School, too. I didn’t like school very much. I didn’t like the food. My mother used to take me home for lunch and bring me back in the afternoon. There are other scenes from my very early childhood that are reconstructed in Paradise Omeros 2002 – a football game, a dance, a male figure.

MB You showed an interest in film and performance from a young age, sneaking into the cinema and becoming involved in the Newsreel Collective and Four Corners Films in East London. What were you looking for?

IJ At some point in 1975 there was a fire in our house on the estate. An electrical fire, which was quite scary. It was obviously a disaster for my family but, for me, it was an exciting moment because I was escaping from the estate where I lived, and where I was being harassed. I didn’t know why. It was only after the fire, after we moved, that I was able to reinvent myself. A whole world opened up in those few years, when I met a group of filmmakers and photographers involved in the Big Flame movement.

We moved to Bruce Road in Bow, a street that was becoming very popular with artists. In fact, as it turns out, one of my later teachers at St Martin’s lived there. Through our neighbours, I became involved in the campaign to revive Kingsley Hall on Powis Road as a community centre. It was a building with an illustrious history – Gandhi had stayed there, R.D. Laing visited, and it had a close connection to the suffragette movement. I began working as a playgroup leader in the youth centre. I was introduced to cinematography, had access to the darkroom, and was taught the principles of photography. I was also introduced to a number of photographers, artists, architects and filmmakers who worked in the Newsroom Collective. That’s how I started work on my first film, Who Killed Colin Roach? 1983 – because of that early interest in photography and filmmaking. Although made when I was a student at an art school, it developed from that culture.

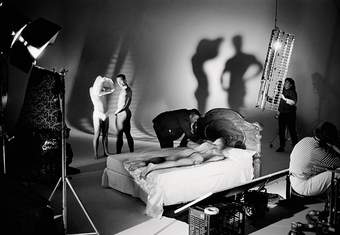

Isaac Julien

Who Killed Colin Roach?, 1983 (detail)

Photographic assemblage of 32 black and white Ilford Classic FB silver gelatin prints

Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Ryan Muller

MB London obviously plays a big part in your early life. How much did the city itself inform your work at this point?

IJ Well, my city is pretty much the East End, but my knowledge was of the East End as my local community. I got to know the West End through clubbing. The city at night. I learned about style and other artists. I would go to Embassy club where Andy Warhol would come with Bianca Jagger on the dancefloor. And I got to know Chelsea through the process of refashioning myself.

MB Through fashion?

IJ Oh, yeah, completely. And through being interested in a kind of representation of myself. The whole question around fashion, the visual iconography of the self, was a form of resistance. The idea of selfstyling and spectacle was part of the body politic of that particular moment.

That was very much inspired by punk rock, soul culture and making trips down the King’s Road to places like Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Seditionaries. I couldn’t afford the clothes, so I’d look through the pages of Italian fashion magazines and pick up items I liked in jumble sales, then sell those on to different places on the King’s Road, in order to buy things for myself.

MB This must have been just before you enrolled at St Martin’s. Going to art school was obviously a formative experience in more ways than one. How did your studies shape your artistic sensibilities, do you think?

IJ Yes. By the time I arrived, the Blitz cultural revolution had started in earnest. I was surrounded by Blitz Kids. You have to remember that the Sex Pistols had their first concert at St Martin’s. There was a certain interdisciplinarity at play – there were lots of people like me who weren’t just interested in art, but also in fashion and music. And all these things were interpolating one another. I was also very interested in politics. What I wanted to do was to bring these things together in the work that I was making, which started to happen in my second year, when I got my video camera. I took it straight to a march, little known to the art professors.

When I graduated, the last thing I wanted to be was a painter, although I really liked painting. I even sold a work at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition! So it wasn’t that I was opposed to painting, but that I thought being a painter would be very boring, and, in a way, conservative or old fashioned. I was very put off by the Royal Academy but then later I became a Royal Academician, funny how things work. You know, in a way, the pivotal moment was obtaining this technology and repurposing it. Because in the studio, we were being taught how to utilise these cameras to create video art. But then I was taking it into the street, to protests and demonstrations.

MB And combining different techniques as well, as in Territories 1984 – where you’re transferring footage, and experimenting with form?

IJ Yes, exactly. There’s a difference between making video art, and making art that is shot on video. I was creating a kind of pastiche or cut-and-mix collage of different genres. I wasn’t interested in fetishising the form as much as I was interested in how video could be utilised to say something that connected to my experiences and echo them.

Being able to experiment and being offered space by our video art teachers, by people like Tina Keane, Anna Thew and Malcolm Le Grice, was really instructional. And you have to remember that around that time, I was being exposed to experimental filmmakers like Chris Marker with Sans Soleil… I’m not quite sure what year that came out.

MB I think, 1983.

IJ Yeah. So by 1983, I’d already seen that genre, and had a model to follow with works like Territories.

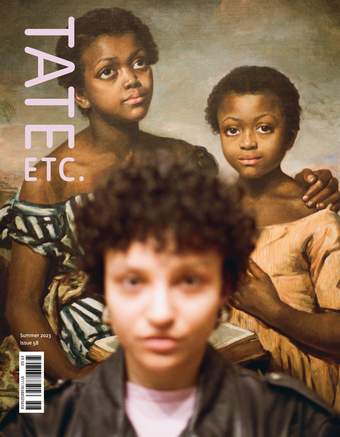

Isaac Julien

Film-Noir Angels (Looking For Langston Vintage Series), 1989/2016

Kodak Premier print, Diasec mounted on aluminium

Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Stephen White & Co.

MB You’ve mentioned the influence of teachers and some of the subjects of your early films. Your work is collaborative in nature – conceived, developed and executed with choreographers, actors, dancers, writers – ‘technicians’, as you’ve called them. What is the impetus behind that collaboration?

IJ Well, I think the ethos of collective practice was something that I was exposed to in my early meetings with Newsreel Film Collective. Because I knew what a film collective was, I had an idea of how they practiced. And in a way, their ‘workshop declaration’ was developed to create a special way of working, which was then called an integrated practice. Which meant that you were involved in making work that was essentially collaborative in nature and involved a community of interest. And through that, you produced work that was formally different.

I started making Who Killed Colin Roach? and it was through that film that I met Nadine Marsh-Edwards, Martina Attille, Robert Crusz and Maureen Blackwood – artists who were involved with the Sankofa Film and Video Collective. In a way, the Sankofa Collective functioned because we were artists from different art schools across London, each with our different ethos and ambition, but we shared a vision.

A collaborative approach developed. By the time I started to make Territories, in the summer of 1983, we were working as a group. So, for example, some members of the collective were shooting Super 8 film in different parts of the carnival, and some were shooting with 16-mm footage, and we assembled the pieces together, adding in footage of performances I had shot in the studio at St Martins with Tina Keane.

MB Your work as a whole also sets out a very ‘intersectional’ viewpoint, to use a current critical term. More simply, you seem to me to always resist simple ‘good versus bad’ oppositions. How important is that to you, in this time of very polarised views?

IJ I think being able to support a range of positions is important. We are in a time of binarisms and essentialisms. And I am suspicious of essentialism. Because behind it, there’s a fixing of terms, most often identitarian, and it can produce a kind of static politics that becomes quite restrictive.

I’ve also been interested in the interstitial space because of the way I make work. Early on, I resisted the difference between video art and experimental film and political film. I was really interested in transgressing that boundary and encapsulating the different forms into one work. And for a moment in time, my work was seen as something which didn’t fit into certain paradigms. Because I was interested in breaking open those paradigms.

And then we had the nuances of intersectionality with Sankofa, in how we produced work. We were different authors, and each member of the collective made their own work, so to speak, but collectively supported each other. I like the idea of multiple perspectives being brought together in a way that can also bring together multiple interests.

Once Again ... (Statues Never Die), 2022

Installation view at Tate Britain, 2023

Isaac Julien. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London. Photo: Jack Hems

MB In many of your films, questions of time and political resistance appear in different ways. It can perhaps be seen most clearly in Looking for Langston 1989, which is recognisably Harlem Renaissance history, but also a portrait of British queer pop culture, set in the repressive cultural politics of the Thatcher era. How do you capture the political mood of a particular time?

IJ Well, the 1980s was a very Orwellian time. But there was this potential for a kind of political resistance which was savvy and energetic. It was a fightback against Thatcherism. There was a whole proliferation of younger people who were involved in what would now be considered countercultural movements – in music, fashion and the arts – but which was, essentially, popular culture. As I said, the idea of fashioning oneself against the dominant class, and against the status quo, was seen as being quite de rigueur. Transgression was the cutting edge.

And I think in a way, the fusing of the art world and disco club culture helped to form the basis for a queer culture that created spaces for celebrating difference, and, at the same time, spaces for exploring your sexuality. You certainly couldn’t find the things that you wanted in the dominant culture. And I wanted that to be part of the aesthetics of my work, you know. To transgress norms and to be able to make works that would somehow bear witness to the countercultures I was a part of.

MB There is a famous club scene in Looking for Langston. Nightclubs, dancehalls and cabarets feature often in your work. Are they spaces of desire, resistance, or both?

IJ Well, both. But I think they’re also the spaces where you can coalesce. They become the conurbations of thinking, in a way; these diasporic mystical dream spaces. Not to make them sound too utopian, but they can become spaces of reinvention, and spaces of possibility. This could be me being nostalgic, or it could be generational.

Do those things still occur? Perhaps not in the same way. One of the things that I find quite exciting is the idea of a club space in a museum and gallery. Again, it goes back to the idea of the experience, and about reconstituting space. It’s something I’m trying to speak to with this exhibition. It’s about what it means to be there, and the way in which the constellations of different communities of interest can come together and experience these things together. In some ways, the exhibition is a gathering of all the aesthetics, disciplines, and public that I’ve engaged with from the 1980s onwards.

MB In many of your previous conversations and texts, certain names reappear as influences or inspirations. Jean-Luc Godard, Robert Bresson, Derek Jarman, Stuart Hall. Are they still important to you?

IJ Yes, absolutely. I went back to the writings of bell hooks when I was making Once Again … (Statues Never Die) 2022, for example. The epilogue scene is a homage to her; it’s actually a text on weather and snow and what it represents, or doesn’t represent, that constitutes the finale of the work. And there are a number of filmmakers today who I find inspiring. Ruben Östlund, the director of Triangle of Sadness 2022, for example, or Mati Diop, and her film Atlantique 2019. I think she’s amazing. Some of the work that Barry Jenkins and Steve McQueen have been making is incredibly exciting.

Isaac Julien: What Freedom Is To Me, Tate Britain, until 20 August. Curated by Isabella Maidment, (former) Curator, Contemporary British Art and Nathan Ladd, Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain. In partnership with Lockton. Also supported by Ford Foundation, with additional support from the Isaac Julien Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council and Tate Patrons.

Maria Balshaw is Director, Tate.

Isaac Julien is an artist based in London.