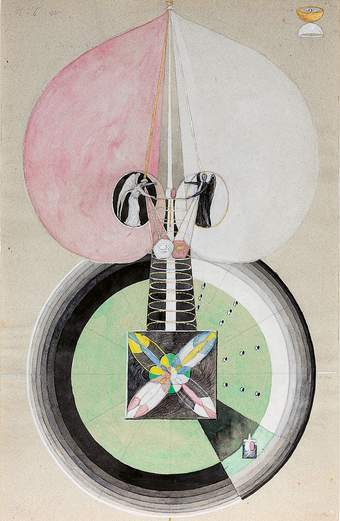

Hilma af Klint

The Eros Series, No 1, The WU/Rose Series, Group II, 1907

Oil paint on canvas

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

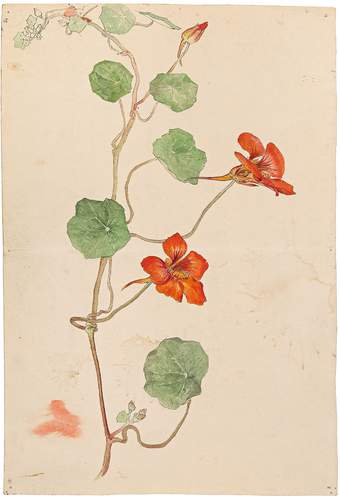

Vegetal forms and symbolism blossom throughout the work of Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint. Botanical illustrations featured prominently in her early naturalistic studies, while endless floral elements suffuse the automatic drawings produced by The Five, the spiritualistic sisterhood of which af Klint was a member. However, af Klint’s interest in plants and the wider natural world goes beyond merely studying the form or classification of flora: rather, her botanical abstractions convey the message that ‘plants are spiritual beings’.

While a keen attention to flora is present across all periods of af Klint’s aristic creation, she took a more pronounced botanical turn in 1918, when she left urban Stockholm and moved to the nearby island of Münso. By this point, she had spent nearly two decades engaging in seances and spiritual gatherings spurred by her deep engagement with the teachings of Anthroposophy, Theosophy, Buddhism, Rosicrucianism, as well as Christian religion. Immersion in the natural world, and the study of plants in particular, provided her with a new limitless portal for mystical insights.

With her lifelong companion and collaborator, Thomasine Andersson, af Klint soon got to work on Flowers, Mosses, and Lichens (1919–20), a notebook in which they explored the vegetal souls of 146 plants and their psycho-spiritual and healing properties.

The qualities of each plant are expressed as abstract geometrical diagrams in vibrant colours, accompanied by explanatory notes. In an entry from 19 May 1919, af Klint represents an aspen as a dark bluegrey and white grid, cut diagonally by a pastel pink shape. The tree is labelled: ‘Obedience. Humility.’ Elsewhere, an apple tree is annotated: ‘Enlighten me about my thoughts. Arrogance. Help me improve the spleen (and liver) of humanity.’

Hilma af Klint

Nasturtium, c.1890

Watercolour and ink on paper

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

These observations indicate a full recognition of the interdependence between human wellbeing and vegetal life. Other notable entries include Convallaria Polygonatum (Solomon’s Seal): ‘Animal Kingdom, Plant Kingdom, Mineral Kingdom. Longing for descent, in order to illustrate practically the union of two hierarchies’, demonstrating af Klint’s concerns with overcoming dualities in life, humanity’s inseparability from the botanical world, and the latter’s role in the project of unification and spiritual evolution.

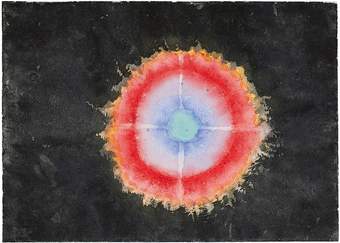

By 1922, af Klint had given up geometric compositions and had begun painting her most ecstatic abstractions – a series of over 70 watercolours that would become known as On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees. In her quest to portray the spiritual forces present in nature, she used a ‘wet-on-wet’ watercolour technique, a method recommended by her teacher (and the founder of the esoteric spiritual movement of Anthroposophy), Rudolf Steiner. For these drawings, and the majority of the works she made up until her death in 1944, af Klint prepared paper by wiping it with a moist sponge, and when she applied watercolour paint, it would run freely, generating nebulous colourful shapes.

Arguably, Anthroposophical influence went beyond the technique of paint application. These dreamy watercolours may have originated from the meditative exercises prescribed in How to Know Higher Worlds (1904), Steiner’s classic guide for the Western esoteric path of initiation and for the attainment of first-hand knowledge of spiritual realities. The exercises call a spiritual practitioner to patiently and devotedly observe the natural world. In one exercise, one’s attention is to be directed towards that which is growing, flourishing and blooming. Another exercise instructs the meditator to observe the phenomena of fading, withering and decaying. These contemplations aim to build spiritual organs of clairvoyance that will enable the student to experience the astral plane or ‘soul world’ and grasp purely spiritual colours expressive of each natural kingdom. In this way, af Klint aimed to access the plant on an etheric plane and so perceive its ensouled nature. In one image, for example, she depicts an aura bleeding from an ear of wheat and saturating the surrounding sheet with intense red, a colour she must have experienced in her meditations as emanating from the grain’s soul.

Hilma af Klint

On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees, 1922

Watercolour on paper

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

Hilma af Klint

On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees, 1922

Watercolour on paper

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

Hilma af Klint

On the Viewing of Flowers and Trees, 1922

Watercolour on paper

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

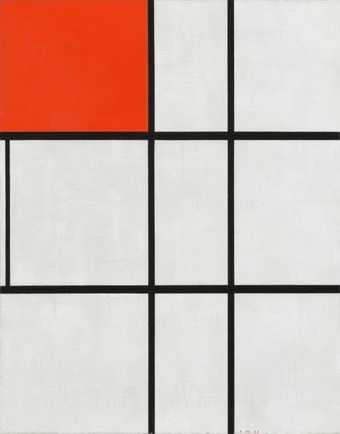

Steiner’s teachings may also have influenced another artist of the period, the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian. In 1908, Steiner travelled to the Netherlands to deliver a series of lectures for the Dutch Theosophical Society, one of which Mondrian attended. It was around this time that the painter started to make his flower paintings, a series of hundreds of works depicting chrysanthemums and irises, amaryllises and roses, often depicted at the withering or decaying stages of their lives.

Some of Mondrian’s flowers appear to have subtle halos around the flowerheads, representing perhaps, just as they did for af Klint, the plant’s astral, or supersensible, substance. For Steiner, these astral shells stood for the eternal cycle of birth, reproduction, decay, material death and regeneration. The Anthroposophist speaks of the relationship between human spirit and plant spirit, but also of the plant’s soul and its connection to mother earth. The flower, in this way, is not just an anthropomorphised representation of human emotions, but a sign for larger realities.

Unlike af Klint, Mondrian chose to represent his flowers naturalistically, in stark contrast to the austere geometric abstraction employed in the rest of his work. For Mondrian, an abstract visual language was used to depict spiritual realities that rose above and beyond the material world known to our senses – something the lowly plant creatures were unable to attain due to their less-than-enviable position at the bottom of the evolutionary ladder. Abstraction was thus reserved for higher, purportedly immaterial realities, while his decision to depict the blooms realistically may be emblematic of his welldocumented and undisguised disparagement of nature and anything green. Mondrian, we read repeatedly in contemporaries’ accounts, was explicit in his renunciation of nature: the artist hated meadows and he fled trees. Characteristically, while Mondrian made floral paintings, the only flower ever seen in his studio was an artificial tulip that he had painted white – a triple kind of loathing: against ‘the pulse of life’ of a living being, against a real flower’s vibrant colourful appearance, and finally, against the feminine element which the bloom was supposed to signify, in its defamed and powerless condition. When a journalist visited him in his studio in Paris, the artist explained that he had whitewashed the leaves to avoid ‘that hideous green of nature.’

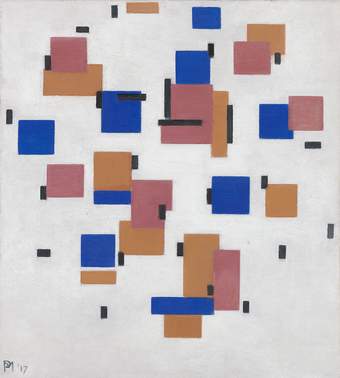

Piet Mondrian

Golden-Banded Lily, 1909-10

Ink and watercolour on paper

2023 Mondrian/ Holtzman Trust. Private collection Smid

Steiner’s teachings present an invisible thread of connection between the Platonist Mondrian and the mystic af Klint, but, while Mondrian took up the challenge of meditating on the plant, I find it unlikely he was disposed to connect on a deeper level with Steiner’s eco-spiritual vision – one that inspired environmental consciousness and laid the foundations for biodynamic agriculture in the later part of the century. Mondrian’s loathing of nature was so profound that he could not even bear to look at vegetation. Such was his aversion that, according to the Dutch critic Jos de Gruyter, when riding a train, he would draw the blinds in his compartment so as not to see the trees.

In Germs of Mind in Plants (1905) the Viennese biologist, Theosophist, and avid neo-vitalist Raoul Francé exclaims: ‘Perception and soul in plants! To have spoken of such things 30 years ago would have at once deprived us of the right to be considered scientific botanists.’ Francé’s publication revolted against mechanistic botany and argued that plants are not unlike humans in that they have senses and purpose. Despite his buoyant remark on the contemporary increase in the interest and understanding of vegetal beings as ensouled creatures, Francé’s important findings concerning the sensory capacities of plants (as well as similar work by Charles and Francis Darwin) have largely fallen mute on subsequent generations of 20th-century biologists – up until the recent emergence of plant intelligence studies. Af Klint, however, understood plants’ unique sensitivity long before contemporary botanical sciences caught up: ‘Behind the effervescent force of a plant is concealed the warmth of feeling,’ she writes (1919, quoted in Hilma Af Klint: A Biography by Julia Voss).

Af Klint’s philosophies bring her close to another mystic and healer: the Mediaeval abbess, writer and composer, Hildegard of Bingen. There are many undulating and spiralling parallels between their lives and ways of thinking, despite an 800-year gap in history. Like af Klint, Hildegard made plants the centre of her unique eco-spiritual philosophy. As a healer working with herbs, she was constantly learning from the vegetal world, and her theology is teeming with ecological and vegetal nuances and connotations. The key concept of Hildegard’s teaching is that of viriditas, the ‘greening green’, or a fresh, self-replenishing power of life that is ingrained in all creation. In accordance with this concept, vegetal life is endowed with a particular vigour and special role for animating the rest of creation, both in material and spiritual terms.

Piet Mondrian

Composition in colour B, 1917

Oil paint on canvas

2023 Mondrian/ Holtzman Trust. Photo Kröller-Müller Museum

The vegetal power of vitality offers the potential to heal the split between matter and spirit – the very split that has contributed significantly to our sense of separation from the more-than-human world and the ecological catastrophe today. Philosopher Michael Marder explains that this split has its roots in the Western philosophical tradition, which has treated the material existence on this planet as infinitely less worthy than the professed life of immaterial spirit. This logic has been gradually secularised and continues to permeate Western thought. In contrast to this male-led tradition, Hildegard imbues ecological relations with theological readings, and her spiritual teachings with vegetal connotations – bringing matter and spirit together again.

Mystical experiences, such as those harnessed by af Klint and Hildegard, can engender a sense of the ultimate unity of all existence: a non-dualistic perspective that views nature and spirit as inseparable. Hildegard’s teachings and af Klint’s art both stem from their mystical visions, which bring about the dissolution of the self into the light of divine love, a sense of the interconnectedness of all beings – just as, we now know, plants and trees are connected to one another and support their kin through underground mycorrhizal networks.

Plants offer us their sublime gift of viriditas, the eternal greening spirit that allows us to breathe, and inspires us to write, create music and art, and to heal and regenerate. With the attention she gives to the vegetal world, Hilma af Klint joins a long and often-repressed lineage of women mystics, herbalists and healers from across the centuries who have sought connections with the more-than-human world and thus have made life in all forms and shapes sprout with meaning and bloom with ensoulment. This is Hilma af Klint’s timeless gift to us.

Hilma af Klint

Tree of Knowledge, No.6, The W Series, 1915

Watercolour, gouache, graphite and ink on paper

Courtesy of The Hilma af Klint Foundation

Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life, Tate Modern, until 3 September. Presented in the Eyal Ofer Galleries. Exhibition organised by Tate Modern and Kunstmuseum Den Haag. Curated by Frances Morris, Director, Tate Modern, Nabila Abdel Nabi, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern, Briony Fer, Professor, University College London, Laura Stamps, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, Kunstmuseum Den Haag and Amrita Dhallu, Assistant Curator, International Art, Tate Modern. Supported by The Af Klint and Mondrian Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members.

Aliya Say is a writer and researcher based in London. Her PhD is dedicated to botanical abstraction in the work of 20th-century artist-mystics, and the parallels between vegetal ontology and mystical states.