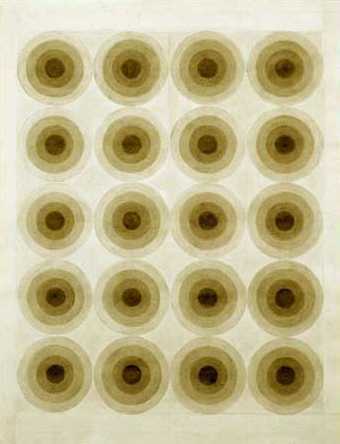

Kathy Prendergast on Eva Hesse’s Untitled 1967

Eva Hesse

Untitled 1966

Ink and pencil on paper

Courtesy Galerie Hauser & Wirth, Zurich © Estate of Eva Hesse

I am automatically drawn to the subtle and understated in art, so it came as no surprise that I was mesmerised by Eva Hesse’s drawing of tiny pencil circles forming a rectangle on a sheet of graph paper

When I revisited the piece with my greatest friend, who is pretty loud with his art and automatically drawn to the overstated, he said: ‘I don’t know why, but that is a phenomenal drawing.’ This made me think more deeply about why something so apparently simple, obvious and straightforward could work so well. In fact, it is so simple that not only could ‘anybody do it’, but probably many artists, myself included, have filled in the squares of a sheet of graph paper with varying degrees of conviction and success. Is it that within the repetitive movement of her circle drawing the varying pressure of the pencil creates almost a separate intangible layer between pencil and paper that resembles an aperture to a different space lying between two and three dimensions? Those circles have structural strength but immense fragility, and, like a net, speak more about the absent space or holes between, rather than their physicality. She has created a grey space that is like a whisper or the swish of wind against your cheek.

I imagine Eva Hesse at her kitchen table, her day’s work done, looking out on the New York rectangular landscape, and after some moments, reaching for her sketch book and pencil. More than anything, this work reminded me of something that I had long forgotten: that art in its purest sense is a form of magic.

Untitled was presented by Mrs Helen Charash, the artist’s sister, through the American Federation of Arts, in 1986.

Antony Penrose on Pablo Picasso’s Weeping Woman 1937

Her vulnerable eyeballs have been violently dislocated from their vaginal sockets. Something has entered their delicate apertures and left her pupils like shattered glass, in which we still see the shadow of the bombers that devastated her life and her home, the little Basque town of Guernica. Like many others that morning she had dressed in her best clothes to go to market. The town was already full of refugees from the nearby fighting, and since before dawn the streets had been filling with farmers and vendors. She would join the amiable throngs of people with their children and their animals. Did she have any idea what the drone of aircraft engines signalled? The images of death and destruction are seared indelibly into her retina and nothing will ever expunge them. She is a victim of the rape of her soul. We don’t need to know the name of the woman behind the shattered eyes. She needs no identity. She is every innocent person whose life has been harmed by violent conflict.

Weeping Woman is on display at Tate Modern. It was accepted by HM Government in lieu of tax with additional payment (Grant-in-Aid) made with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the National Art Collections Fund and the Friends of the Tate Gallery in 1987.

Tal R on Thomas Johnson’s View of Trinity Chapel Triforium, Canterbury Cathedral seventeenth century

Thomas Johnson, formerly attributed to Unknown artist, Britain

View of Trinity Chapel Triforium, Cantebury Cathedral

Tate

Some time ago I was living with my former girlfriend’s parents. I spent most of the day alone in their kitchen gazing at the decorations – a soda machine, dried straw, spruce cones, cereal boxes and a picture stuck on the fridge with magnets that looked like van Gogh’s painting Corridor in the Asylum.

My diet then was mainly different kinds of cereals. Being full and satisfied, I would lie on the table next to vitamin pills and toothpicks and study the picture. It was a corridor to all my longings. It was the song Eye of the Tiger by Survivor. It was a yellow road, up, up, up. It was a pure handsome road to ruin. Then the shadow man to the right of the picture would bring me back to the kitchen with his terrible insecure false voice. He is the minute man. He pretends to be a cripple to get people’s attention. He talks to girls about emotions and mothers about lack of emotions from husbands. The only normal thing about the minute man is that he has ten fingers. But that is because his fingers are also clean.

Lately I have been living in a new place, and I’m ashamed to admit that I don’t remember who did that corridor drawing on the fridge. I feel no bitterness towards the shadow on the right side of the picture who prevented me from complete free fall. I asked a friend of mine to call my former girlfriend’s parents and pretend it was me and ask them who did the forgotten drawing on the fridge. They told him it was by Thomas Johnson, and the shadow to the right was the butterfly man – while everybody is busy getting born or dying, he sneaks out in the night with his flashlight and points it to the surprised moon and allows all butterflies to circle around in the glow from the flashlight. He correctly says his name is Minus.

View of Trinity Chapel Triforium, Canterbury Cathedral was purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund in 1996. Van Gogh’s Corridor in the Asylum (1889) is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Ian Kiaer on A Family Group in a Garden British School, c.1754

If it rained, things would get spoiled. The man’s slippers are not meant for puddles. The table cloth would offer little protection to the polished surface beneath. Even this watercolour, caught by just a few drops, would blot. Maybe if they hurried, the party could make it to the folly nearby. There is something fragile about the whole scene: just for a time what belongs indoors has ventured out, but nothing here is intended to stay.

That’s if the outside is outside. It is hard to tell with eighteenth-century landscapes designed to be paintings whether what we are looking at is tamed nature, or a cyclorama in a studio. The caption attributes it possibly to Gainsborough, known for his broccoli models of parks. So maybe this is a painting of a model – a model of a park, which in turn is a model of a painting. One stands in for the other and nothing is quite clear.

That is the mischief of theatre: to play with different scales, masks and plots; to propose and affect; to offer what might be rather than what actually is. This time it is happy families around a table, next it might be romance or an intrigue within the folly. Such a building is well suited to thought and idle moments, where things are brought into being and tried out. The watercolour itself will always remain a model, intricately made from unstable substance, easily adjusted and just as easily left in a drawer.

A Family Group in a Garden is on display at Tate Britain. It was bequeathed by Alan Evans in 1974.