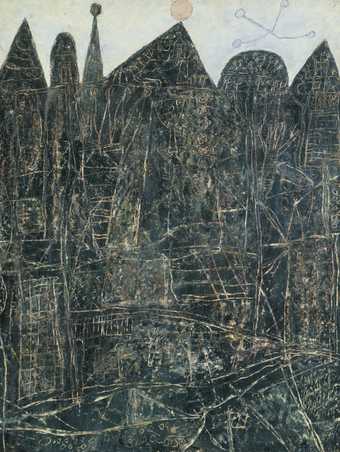

Frank Auerbach

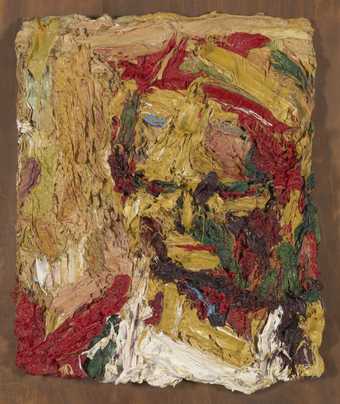

Head of E.O.W. I

(1960)

Tate

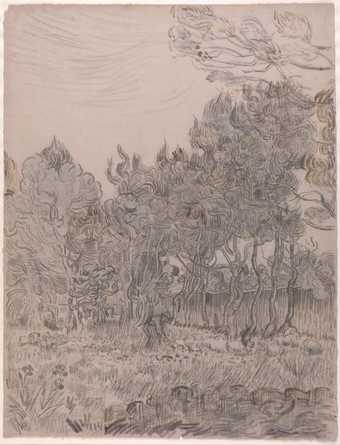

First noticeable in the paintings of Venetian Renaissance artists Titian and Tintoretto, impasto is also seen in Baroque painting, for example in the work of Rubens. It is increasingly notable in nineteenth-century landscape, naturalist and romantic painting.

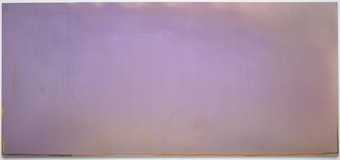

The use of impasto became more or less compulsory in modern art as the view took hold that the surface of a painting should have its own reality rather than just being a smooth window into an illusionist world beyond. With this went the idea that the texture of paint and the shape of the brushmark could themselves help to convey feeling, that they are a kind of handwriting that can directly express the artist’s emotions or response to the subject. (See also gestural.)

A painting in which impasto is a prominent feature can also said to be painterly. This term carries the implication that the artist is revelling in the manipulation of the paint itself and making the fullest use of its sensuous properties.

The idea that the artist should place emphasis on the innate qualities of their medium is a central one in modern art, and is summarised in the phrase ‘truth to materials’. (See also direct carving).

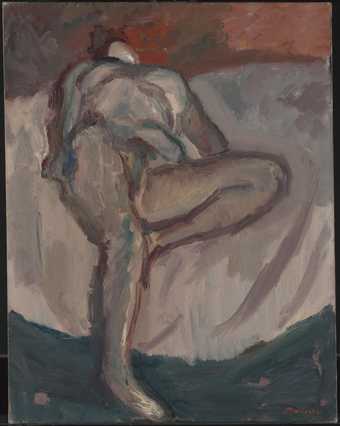

In the mid-twentieth century, some artists took impasto to the extreme, as seen in the work of Frank Auerbach, Jean Dubuffet and Leon Kossoff.