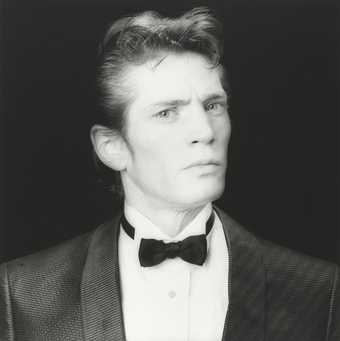

Robert Mapplethorpe

Louise Bourgeois

(1982, printed 1991)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Introduction

With a career spanning eight decades from the 1930s until 2010, Louise Bourgeois is one of the great figures of modern and contemporary art. She is best known for her large-scale sculptures and installations that are inspired by her own memories and experiences.

Using drawings, prints, sculpture and fabric works from the ARTIST ROOMS collection, this resource takes an in-depth look at her work through the themes and ideas of this extraordinary artist.

Meet Louise Bourgeois

Before exploring the themes behind her work, meet the artist. In this video, Louise Bourgeois lets us into her home and shares insights into her life and work.

Themes

I need to make things. The physical interaction with the medium has a curative effect. I need the physical acting out. I need to have these objects exist in relation to my body.

Louise Bourgeois

Childhood Trauma

Whatever materials and processes Louise Bourgeois used to create her powerful artworks, the main force behind her art was to work through her troubled childhood memories. These memories were not specific, but a layering of emotional responses to the complicated relationship she had with her parents and their relationship with each other.

Abandonment

Bourgeois’s mother, Joséphine, suffered from ill health and Louise cared for her for long periods of time. Josephine died when Louise was just 22. This, and her father’s unfaithfulness (he had a series of mistresses), led to a fear of abandonment, a key theme in Bourgeois’s work. The backdrop of the First World War, which began when she was three years old, made her traumatic memories of childhood even more intense.

Opposing forces

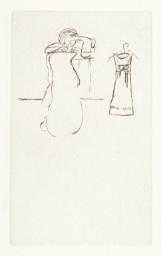

Louise Bourgeois

Sewing

(1994)

Tate

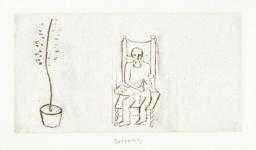

Louise Bourgeois

Paternity

(1994)

Tate

Louise Bourgeois

Janus Fleuri

(1968)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by The Easton Foundation 2013

Bourgeois’s mother and father had very different characters. Her mother had a logical and intellectual approach to life, in contrast to the emotive and passionate character of her father. These opposing forces became a key theme of much of her later work. Her double-headed sculptures suggest the sense of two very separate forces relentlessly attached together. Janus Fleuri 1968 consists of two forms joined back to back but apparently pulling away from each other.

The spider

In 1947 Louise Bourgeois drew two small ink and charcoal drawings of a spider. Fifty years later in the late 1990s, she created a series of steel and bronze spider sculptures.

In a 2008 film made about her life, Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress and The Tangerine, Bourgeois described these spider sculptures as her ‘most successful subject’. Bourgeois uses the spider, both predator (a sinister threat) and protector (an industrious repairer), to symbolise the mother figure. The spinning and weaving of the spider’s web links to Bourgeois’s own mother, who worked in the family’s tapestry restoration business, and who encouraged Louise to participate.

What Do You Think? Materials and Meanings

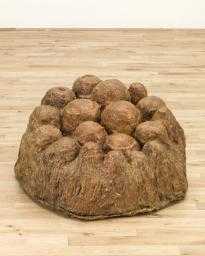

Louise Bourgeois

Amoeba

(1963–5, cast 1984)

Tate

Explore the different materials Louise Bourgeois used.

- Look at Louise Bourgeois's work in Art & Artists.

- Think about what the different materials she uses adds to how the artworks look and the tactile effect they give the work.

- Think about what emotions the materials might reflect and how this affects your interpretation of the work.

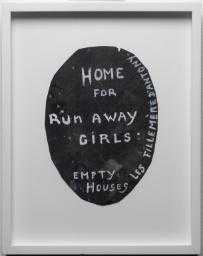

Home

I was in effect a runaway girl. I was a runaway girl who turned out alright.

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois

Home for Runaway Girls

(1994)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2013

In 1938, just before the breakout of the Second World War, Louise Bourgeois left Paris for New York with her new husband Robert Goldwater. This move away from everything that was familiar affected her greatly. Early paintings in New York such as Runaway Girl c.1938 depict Bourgeois leaving behind her childhood home. Fallen Woman (Femme Maison) 1946-7 depicts a female figure with her head and torso covered in a house. Bourgeois wrote:

She does not know that she is half naked, and she does not know that she is trying to hide. That is to say, she is totally self-defeating because she shows herself at the very moment that she thinks she’s hiding.

Running away

Louise Bourgeois’s longtime assistant, Jerry Gorovoy, compares Bourgeois from this period with Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz 1939:

Like the young runaway Dorothy Gale from Kansas, Bourgeois has been on a journey to alleviate a core experience of abandonment.

Bourgeois revisited the theme of running away from home in the drawing Home for Runaway Girls 1994. In this work the words ‘HOME FOR RUNAWAY GIRLS: EMPTY HOUSES. LES FILLE MERE D’ANTHONY.’ are painted in gouache on sandpaper. (Mere D’Anthony was a real girls’ home in Paris). Bourgeois reminds us of her ongoing feelings of displacement and her belief in art as form of therapy and escape. The artwork is oval shaped and looks a little like a door plaque. But the rough textured surface looks at odds with the comforts usually associated with ‘home’.

The fallen woman

Bourgeois returned to the theme of the fallen woman in her sculpture Fallen Woman 1981, a small bronze sculpture, with a woman’s head attached to a phallic-shaped handle. It looks like a club or truncheon. The figure looks sad and pathetic, and unable to make use of the power suggested by her weapon-like form.

Bourgeois said that her early work could be related to ‘a fear of falling’ and ‘later a fear of failing’.

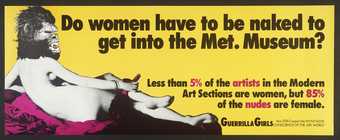

Women vs. home

Themes of domestic life and the home reoccur throughout Louise Bourgeois’s work. Early works on canvas and paper from the mid-1940s show a female figure trapped inside a small-scale house. While her room-like Cell structures often contain objects associated with the home. Bourgeois explores the role of female identity throughout her work, often challenging the conventional role of women in the twentieth century.

Fear and Anxieties

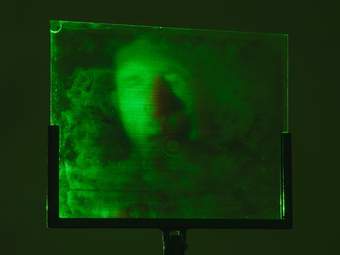

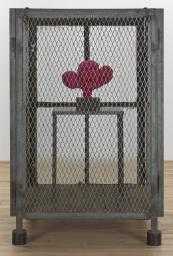

Louise Bourgeois

Cell XIV (Portrait)

(2000)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

Louise Bourgeois

Cell (Eyes and Mirrors)

(1989–93)

Tate

Louise Bourgeois began to make her self-enclosed structures known as Cells in 1989 and they became an important part of her output for many years. In these works she explores themes of being trapped, anguish and fear. The word ‘cell’ can refer to both an enclosed room, as in a prison; as well as the most basic elements of plant or animal life, as in the cells of the body. This is how Bourgeois decsribed how seh saw the Cells:

Each cell deals with a fear. Fear is pain... each cell deals with the pleasure of the voyeur, the thrill of looking and being looked at

Cell XIV (Portrait) 2000 houses a metal table on which a red fabric sculpture sits on a small pedestal. The fabric sculpture is of three screaming heads which are joined together. The three fused heads suggest Cerberus, the three-headed dog in Greek mythology. In depictions of Cerberus each head is often used to represent birth, youth, and old age. The cycle of life is a theme that Bourgeois often explored in her work.

Cell (Eyes and Mirrors) 1989-93, one of Bourgeois’s first cells, has a large rough marble stone supported by steel girders at its centre. The stone has carved and polished black eyes that look up towards a large circular mirror. Other mirrors inside the cell look like dressing-table mirrors or oversized vanity mirrors. They suggest the idea of home. In the wire mesh ceiling the large round mirror is attached to a hinged circular panel. This can rotate to reflect different views of the interior. Walking around the sculpture is unnerving as the eyes and mirrors both confront and reflect you. Bourgeois wrote:

It is the quality of your eyes and the strength of your eyes that are expressed here. Nobody is going to keep me from seeing what is instead of what I would like

Through Cells (Eyes and Mirrors) Bourgeois invites us to think about reality and what reality means.

Found objects and meaning

Bourgeois’s use of found objects in her Cells reflects the influence of the artist Marcel Duchamp, who she once referred to as a father figure. Duchamp first used found objects in the early twentieth century. He presented these objects as artworks, calling them his ‘readymades’. But whereas Duchamp’s selection of objects was about the idea of the object, Bourgeois’s selection is rooted in memory and biography. The objects mean something to her.

Marcel Duchamp

Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy?

(1921, replica 1964)

Tate

© Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2024

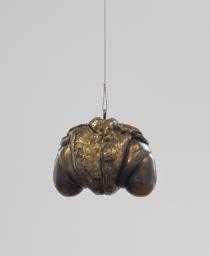

Body Parts

Our own body could be considered, from a topological point-of-view, a landscape with mounds and valleys and caves and holes. So it seems rather evident to me that our body is a figuration that appears in Mother Earth.

Louise Bourgeois

From her earliest paintings to her later Cells and fabric works, Louise Bourgeois explores the human body. In the 1960s, the body forms and body parts in her sculptures became more organic, very different from earlier sculptures in both shape and the materials she used. She began to use materials such as latex, plaster, marble and bronze. She also used and repeated rounded forms suggestive of male and female genitals and breasts.

Tits 1967 is a small sculpture cast in bronze. The sculpture, as the title indicates, represents two breasts fused together to create a single bulbous form. This double, mirrored form is something that Bourgeois uses a lot in her work, and shows the influence of surrealism. Tits relates to Janus Fleuri 1968 where two stunted phalluses are joined back to back to create a sexualised form that suggests both male and female organs. Both Tits and Janus Fleuri point in opposite directions – the past and the future – suggesting the importance of the past to Bourgeois.

In sculptures such as these, Bourgeois used fragmented body parts to investigate complex emotional states. They appear regularly in Bourgeois’s work and are often referred to as ‘part-objects’. The term ‘part-object’ was first used by the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein in her writings on the development of young children. In Klein’s view, the first ‘part-object’ we encounter in life is our mother’s breast. This idea of the ‘part-object’ has since often been used to describe sculptures by modern and contemporary artists that take the form of body parts in exploring sexuality, desire or questions of gender.

Have a go: Body hybrids

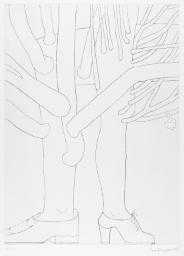

Louise Bourgeois

Tree with Shoes

(1998)

Tate

Collaborate with a friend or family member (or group) and play this drawing game.

- Draw a head and neck on a piece of paper. Fold the paper so you hide your drawn head but leave a few marks that show where your drawn neck ends. Pass the paper to your collaborator to draw the body. They should then fold the paper again and pass it back to you (or on to the next person if you are in a group) to draw the legs. Pass the paper on again to draw the feet.

- Unfold the drawing to find a hybrid body.

- Now change the activity by adding some objects. Draw in a shoe or table or plant, instead of sections of the body, to see what happens.

This process of making drawings was invented by surrealist artists at the beginning of the twentieth century. They called this process exquisite corpse (cadavre exquis in French). Other artists have since used the process to make unsettling drawings, including contemporary artists Jake and Dinos Chapman. Explore the Chapmans's exquisite corpse drawings in Art & Artists.

Spiral

The spiral is important to me. It is a twist. As a schild, after washing tapestries in the river, I would turn and twist and ring them ... Later I would dream of my father's mistress. I would do it in my dreams by ringing her neck. The spiral – I love the spiral – represents control and freedom.

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois first used the spiral form in the 1950s in two wooden sculptures and it often appears again in later works. For Bourgeois the form of the spiral comes from the twisting of tapestries in the River Bièvre when she worked as a child and young woman in the family business.

The spiral represents ‘an attempt at controlling the chaos’. In the sculpture Nature Study 1986 a tightly coiled spiral morphs into a hand holding a human figure.

Louise Bourgeois

Spirals

(2005)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2013

Louise Bourgeois

Nature Study

(1986)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

The spiral also suggests violence – the wringing of necks. In the hanging bronze sculpture Spiral Woman 1984 the figure is bound by a thick coil, with only her limbs visible. Trapped by the spiral she hangs in mid-air, suspended and spinning in a constant state of her own fragility.

Although the spiral can control chaos, there is always the underlying threat that the spiral will unravel.

In A l’infini 2008-9 spirals are present again. Here, the spiralling lines flow freely around representations of falling female bodies, disembodied limbs, a couple and childbirth. Interlocking etched ribbon-like lines in the multi-part work suggest a double helix – the spiral arrangement of the two strands of DNA that froms the basis for life itself. A l’infini refers to the endlessness of life. It abstractly puts across the idea of life as a journey, moving from birth, to youth, to relationship with a partner, and ultimately, to death. Birth, love, sexuality and death are an endless loop in the cycle of life.

The spiral can also be seen in a series of twelve woodcuts named Spirals from 2005. Some of the spirals are loose and sketchy while others are more tightly wound and even.

Friendship

When you are at the bottom of the well, you look around and say, who is going to get me out? In this case it is Jerry who comes and he presents a rope, and I hook myself on the rope and he pulls me out.

Louise Bourgeois, interveiw with Lawrence Rinder 9 May 1995, in Frances Morris (ed.) Louise Bougeois, 2007, p.150.

Jerry Gorovoy met Louise Bourgeois in the late 1970s and was her assistant and best friend for over thirty years. Bourgeois made lots of drawings and sculptures of Jerry Gorovoy’s hands along with her own hands. She referred to these as intimate ‘portraits’. The Welcoming Hands 1996, located in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris, is a bronze sculpture of her hands clutching those of Jerry’s.

Bourgeois also depicted a representation of her friendship with Gorovoy in the multipart work 10 am Is When You Come To Me 2006. It consists of twenty hand-painted sheets that depict her hands and those of Gorovoy. The hands are mostly painted over printed musical score paper in red gouache paint. You can tell Bourgeois’s hands by the wedding ring she wore. The title relates to the time Gorovoy would arrive at Bourgeois’s studio or home to begin their daily routine working together.

Louise Bourgeois

Give or Take

(2002)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2013

Louise Bourgeois

10 am is When You Come to Me

(2006)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2013

Hands reoccur in many of Bourgeois’s works, often as a symbol of being dependent on someone who supports you. Give or Take 2002 can be read as a commentary on the sometimes conflicted reliance of friendship. This sculpture presents a two-handed limb – one open, the other clasped – an object that is simultaneously gentle and cold.

Earlier in her career Bourgeois had also used friendship as inspiration. Personages 1946-55, are totem-like wooden sculptures that she grouped together to create installations. They depict individuals and Bourgeois’s relationship with them, reflecting her homesickness and the people she left behind in Paris. Knife Couple 1949 is an example of these. Bourgeois often used her roof as a studio and the tall forms of the Personages suggest the skyscrapers and rooftops that surrounded her.

Writing and Recording

I love language... you can stand anything if you write it down... words put in connection can open up new relations... a new view of things.

Louise Bourgeois

Louise Bourgeois kept journals from a young age. Her childhood experiences were hoarded in her diaries and she continued to write and record her thoughts, activities and experiences throughout her life. As well as using the writing in her journals as a memory bank of ideas for her work, she also included text from her journals in her artworks.

In 1947 Louise Bourgeois produced a group of prints called He Disappeared into Complete Silence that combined poetic text with engravings. Bourgeois later combined words, phrases and drawing in her artworks, sometimes embroidering these onto cloth. The text she uses is aimed at the viewer and includes didactic (or preachy), ironic and sometimes moralising statements. These are either presented playfully, or, as critic Robert Storr says, ‘with jarring psychological’ bluntness.

In Repairs in the Sky 1999, one of a series of lead wall reliefs, the title of the work is engraved into the surface in capital letters. Around the text are five cavities, which resemble bullet holes that pierce into the lead. These have been ‘repaired’ with fabric and thread. Here, Bourgeois again combines opposing elements: the soft lead, thread and fabric are contrasted against steel, which has been hammered and distorted with the cavities and the text engraving.

In the woven fabric piece I Am Afraid 2009, Bourgeois lists her fears as silence, the darkness, falling down, insomnia and emptiness. These are themes and anxieties that reoccur throughout her work. Bourgeois was an obsessive list-maker with a fascination for dictionaries and encyclopedias, perhaps because of their sense of completeness and certainty.

Bourgeois also kept three types of diaries. She described these as:

The written, the spoken (into a tape recorder), and my drawing diary, which is the most important. Having these diaries means that I keep my house in order.

Like drawing, writing was a compulsion for Bourgeois;

her writings are a collection deeply personal thoughts and memories like her sculptures and drawings.

What do you think? Text and language

I love language ... you can stand anything if you write it down ... words put in connection can open up new relations ... a new view of things.

Louise Bourgeois

the written, the spoken (into a tape recorder), and my drawing diary, which is the most important. Having these diaries means that I keep my house in order.

Louise Bourgeois

- Think about these quotes by Louise Bourgeois and how they relate to her artworks.

- Look at her use of language in artworks such as Home for Runaway Girls and I Am Afraid. Identify when you feel she is being didactic (teaching or instructing us about something), ironic (sarcastic or tongue-in-cheek), or moralising.

Have a go: Words, motifs and narratives

Louise Bourgeois

I Am Afraid

(2009)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2013

Do you keep a diary or journal? Or do you write 'to do' lists or write things down that you want to remember?

- Pick out phrases or words that are important from your writing.

- How would you use these in an artwork to add meaning?