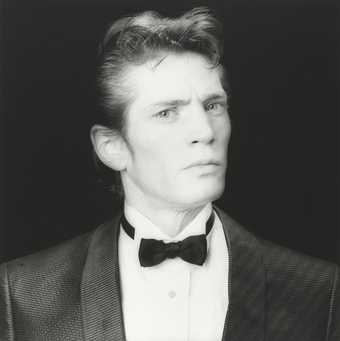

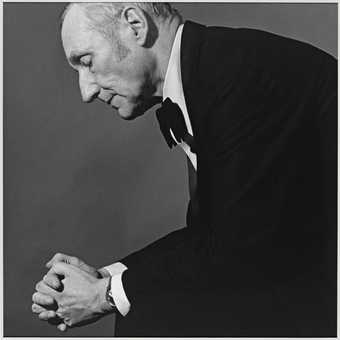

Robert Mapplethorpe

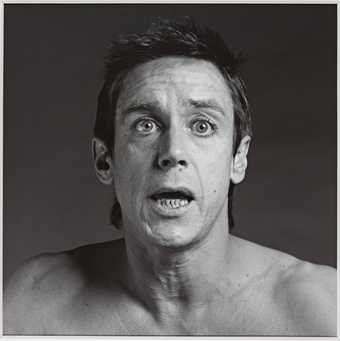

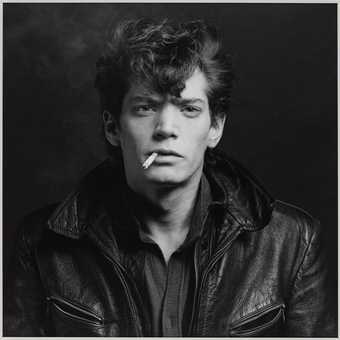

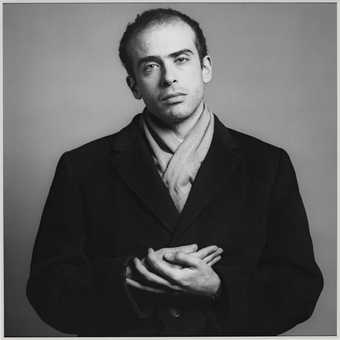

Nick Marden

(1980)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Introduction

I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before

Robert Mapplethorpe, Art News, 1988

Robert Mapplethorpe is best known for his powerful black-and-white portraits and self-portraits. His photographs both challenge us and present us with images of classical beauty.

Using Mapplethorpe's photographs in the ARTIST ROOMS collection this resource takes an in-depth look at some of the key themes Mapplethorpe explored in his work.

Who is Robert Mapplethorpe?

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1980, printed 1990)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 2014

Robert Mapplethorpe was born in 1946 in Queens, New York. One of six children, he was brought up in a strict Catholic environment. When he was sixteen he enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he studied drawing, painting, and sculpture.

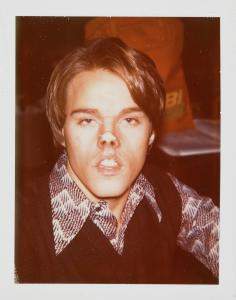

From Polaroid to professional

Early in his career Robert Mapplethorpe was influenced by a range of artists including assemblage artist Joseph Cornell and dada artist Marcel Duchamp. He experimented with mixed media collages, using images cut from books and magazines.

In 1970 he bought a Polaroid camera so he could take photographs to use in his collages. But he began to appreciate the quality of Polaroid photographs in their own right and his first solo exhibition, in 1973 at the Light Gallery in New York City, was called Polaroids. Two years later Mapplethorpe bought a more sophisticated camera, a Hasselblad medium format camera, and began photographing the people he knew. Artists, musicians, pornographic film stars, and other members of the edgy New York underground scene were all captured on Mapplethorpe's camera.

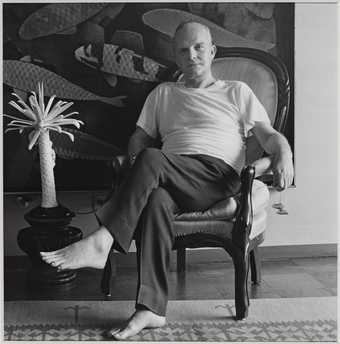

Robert Mapplethorpe

Truman Capote

(1981)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Robert Mapplethorpe

Marianne Faithfull

(1976, printed 2003)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Robert Mapplethorpe

Iggy Pop

(1981)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Mapplethorpe’s career flourished in the 1980s and he continued to explore and refine his techniques and formats. He also worked on commercial projects, creating album cover art for the musician Patti Smith and the band Television, as well as a series of portraits and party pictures for Interview Magazine.

Despite (or perhaps because of) being diagnosed with AIDS in 1986, he accelerated his creative efforts, undertaking increasingly ambitious projects. In 1988, a year before his death, he had his first major exhibition at The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

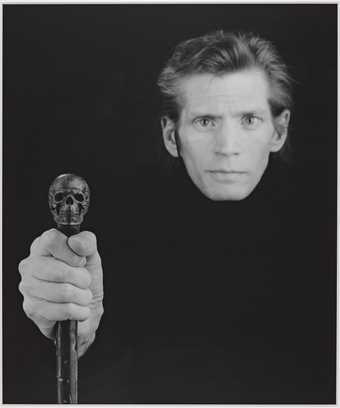

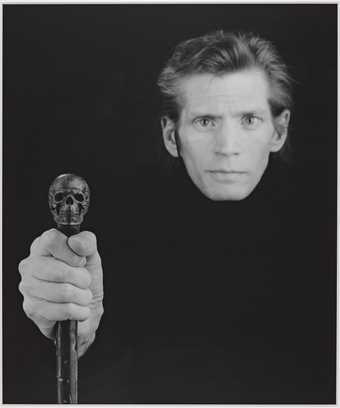

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1988)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Mapplethorpe’s legacy

Today Mapplethorpe’s work can be found in the collections of major museums around the world. Beyond the art-historical and social significance of his work, his legacy lives on through the work of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. He established the Foundation in 1988 to promote photography, support museums that exhibit photographic art, and to fund medical research in the fight against AIDS and HIV-related infection.

Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith: Artist and Muse

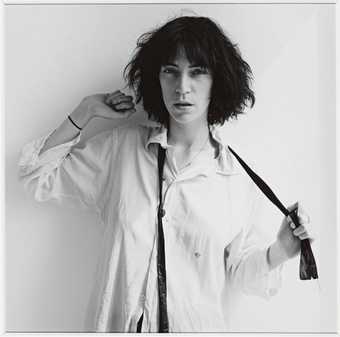

Robert Mapplethorpe

Patti Smith

(1975)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Musician and poet Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe had a unique relationship: they were friends, lovers, artistic collaborators and soul mates. They met in 1967 and lived together for the next few years. In 1970 they moved together into the Chelsea Hotel in New York, the historic hotel known for its famous residents including many writers, artists and musicians.

Robert Mapplethorpe took many photographs of Patti Smith. He photographed her for the cover of her 1973 volume of poetry, Witt, and her album Horses in 1975. Horses went on to achieve iconic status in popular music and defined Smith’s androgynous and uncompromising style. In Mapplethorpe’s photograph Patti Smith 1975, Smith’s pose is both vulnerable and confrontational. She wears a disheveled shirt and leans against a wall staring at the camera. But her raised arm pose gesture of playing with her tie, makes her seem nervous and unsure.

Mapplethorpe photographed Smith again for her fourth album, Waves in 1979. By this time she had achieved commercial and critical success and had decided to take a break from her music career. She had met and fallen in love with the American musician Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith, and wanted to focus on family life. Her music on Waves reflects a new sense of calm, charm and sincerity and Mapplethorpe captures this in the image he took for the album’s cover.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Patti Smith

(1979)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Although Smith still has a piercing stare, she looks somewhat gentler. The light fabric of her dress, the tree that obscures part of the body and the doves that rest on either hand give the image a serene look. The last album cover photograph that Mapplethorpe took for Patti Smith was for her 1988 album Dream of Life.

Patti Smith wrote the foreword (an introduction that often appears at the beginning of a book) for one of Mapplethorpe’s final projects, Flowers, a book of his flower studies. This was published several months after his death.

What do you Think? Artists and muses

I was his first model, a fact that fills me with pride. The photographs he took of me contain a depth of mutual love and trust inseparable from the image. His work magnifies his love for his subject and his obsession with light. So, as one who has stood before the camera of many artists and friends, I can only advise a photographer to love his subject, and if this is not possible, love the light that surrounds her.

Patti Smith, Time, 2011

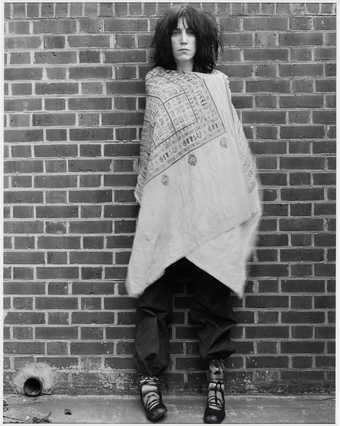

Robert Mapplethorpe

Patti Smith

(1976, printed 2005)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

What role do you think the muse plays in an artist’s work?

How do you think a close relationship between an artist and their sitter affects the work?

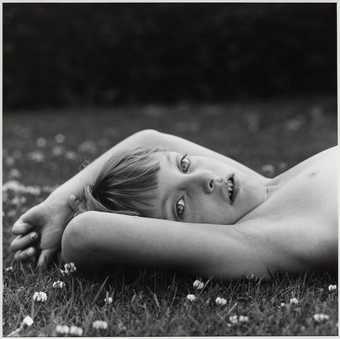

Children

Robert Mapplethorpe

Honey

(1976)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Robert Mapplethorpe

Eva Amurri

(1988)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Mapplethorpe took a number of photographs of children throughout his career. They were mostly children of friends, or sometimes he was commissioned by society figures to photograph their children. In contrast to his highly posed portraits of adults, his images of children emphasise their innocence, lack of self-consciousness and sense of playfulness. His approach to photographing children was inspired by the photographs of Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron.

Mapplethorpe felt strongly that he should have the consent of the people he photographed and once stated that children were the most difficult subject to photograph: ‘you can’t control them. They never do what you want them to do.’

Robert Mapplethorpe

Lindsay Key

(1985)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

In the photograph Lindsay Key 1985, the little girl looks away from the camera, perhaps avoiding the gust of wind that we see catching her hair and dress. Her posture and bare feet suggest a playful nature and make her look relaxed. Mapplethorpe photographed her outside the studio, which is untypical of much of his work from this time. The dark shadows cast by the girl contrast strongly with her white dress, while trees throw abstract shadow shapes in the background. Although he captures her innocence and playfulness, Lindsay looks confident, cool and solemn in the photograph – and very much her own person.

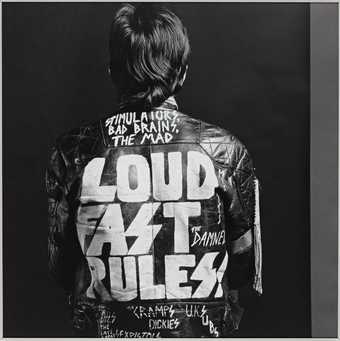

Portraits: Artists and Celebrities

Portraiture was one of the main strands of Mapplethorpe’s work.

His subjects were from a wide range of social and cultural contexts: from royalty and aristocracy to rent boys. A large proportion of his portraits from the 1980s were of prominent figures in the arts, such as Truman Capote, William Burroughs and Andy warhol; and his portraits can be seen as a reflection of New York’s ‘cultural scene’ at that time. But whoever he photographed, all the images are characterised by Mapplethorpe’s style – his relentless pursuit of beauty with no imperfections.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Louise Bourgeois

(1982, printed 1991)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Robert Mapplethorpe

Doris Saatchi

(1983)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Robert Mapplethorpe

William Burroughs

(1980)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

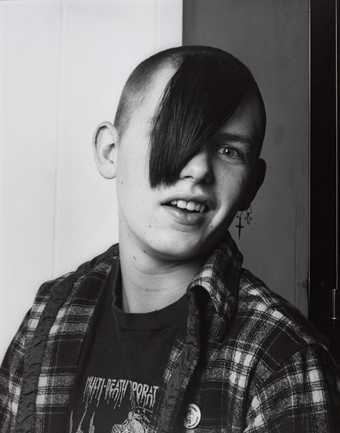

Robert Mapplethorpe

Tattoo Artist’s Son

(1984)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Rather than putting across the character of each sitter, the photographs reflect Mapplethorpe’s vision – showing his perfect idea of the sitters. The critic and curator Janet Kardon describes Mapplethorpe’s portraiture subjects as ‘avatars for his vision’.

In 1984 Mapplethorpe photographed Grace Jones, the Jamaican-American singer, songwriter, model and actress. Jones, known for her androgynous looks and her provocative behaviour, was a prominent figure in the New York art and social scene in the 1980s. Mapplethorpe’s photograph of Grace Jones shows her before a performance at Paradise Garage, an alternative dance club in New York City. The artist Keith Haring had decorated her in body paint. Keith Haring had been introduced to Grace Jones by Andy Warhol, and Warhol also arranged for Mapplethorpe to photograph her.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Grace Jones

(1984)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Although a collaborative project, the photograph itself is classic Mapplethorpe. Grace Jones is photographed straight on facing the camera and appears in complete symmetry. Jones often adopts male-looking personas in her performances, challenging representations of the female body. She transforms her body into a site of power and Mapplethorpe’s strong formal image of her captures this.

Have a go: Creating a scene

Robert Mapplethorpe

Marianne Faithfull

(1976, printed 2003)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Mapplethorpe’s subjects often represent a particular cultural scene; with figures such as Andy Warhol, Marianne Faithful and Grace Jones.

Create a collage bringing together figures who you feel are part of an equivalent scene today.

The Body and Sculpture

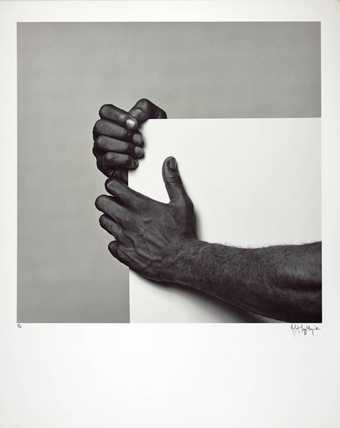

Robert Mapplethorpe said that he sought ‘perfection in form’ in all his subjects, from nudes and portraits to flowers and architecture. This perfection can be clearly seen in his studies of the human figure. These powerful bodies remind us of classical Greek sculpture and follow the rules of symmetry and geometry that classical sculptors used.

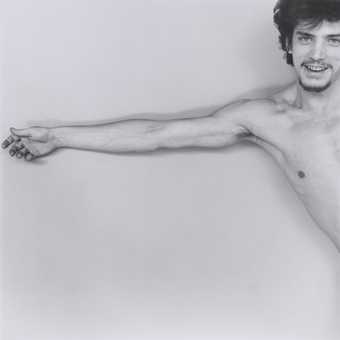

In 1980 Robert Mapplethorpe met Lisa Lyon, the first World Women’s Body Building Champion. They worked together over the next few years creating various portraits and figure studies including both full and fragmented body images. In these photographs, which were published in a book in 1983, Lady: Lisa Lyon, Lyon took on different guises and played with the idea of ‘types’ of women.

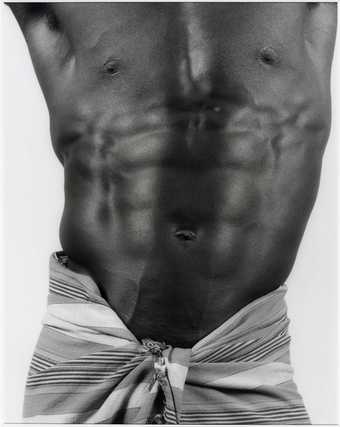

During this time Mapplethorpe was also photographing the male figure. His sitters were often athletic black men including models, dancers and bodybuilders, all with muscular and well-defined bodies. He chose black models because, as his biographer Patricia Morrisroe suggested, ‘he could extract a greater richness from the colour of their skin’. The images, which were published as Black Book in 1986, included photographs of fragmented bodies such as a torso, an extended arm, buttocks and thighs. Mapplethorpe once stated ‘I zero in on the body part that I consider the most perfect part in that particular model’.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Derrick Cross

(1983)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Robert Mapplethorpe

Lowell Smith

(1981)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Mapplethorpe’s black sitters included the athlete and model Ken Moody and the dancer Derrick Cross. In the work Derrick Cross 1983, the frame is filled by Cross’s torso. The arch of the body suggests movement while the draped fabric around the waist enhances the sense of performance and sculpture. The twisting movement of the bosy highlights Cross’s muscle definition, emphasising his physicality and strength.

Mapplethorpe’s work is often compared to that of the old masters and artists of the Renaissance. In a 2009 exhibition Mapplethorpe: Perfection in Form, at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence, Italy, his photographs were presented alongside great Renaissance masterpieces such as Michelangelo’s David 1504.

Have a go: Sculpting in 2D

Mapplethorpe’s eye for a body was that of a classical sculptor in search of an ideal

Bruce Chatwin, introduction to the book Lady: Lisa Lyon 1983

Sculpture is a three-dimensional art associated with carving, modelling, casting or constructing; yet Mapplethorpe once said that ‘photography is a great way to make a sculpture’. What do you think he meant by this?

Create your own two-dimensional sculpture. This could be a photograph or a drawing. Think about materials and processes you could use to create a sense of form and structure.

Think about how you would use tone (lights and darks) to suggest three-dimensional forms, strong horizontals and verticals to create a feeling of solidity and structure, and perspective techniques to create the impression of three-dimensional space.

Self-Portraiture: Identity and Mortality

While images of the body are associated with ideals of beauty, the portrait is often associated with identity and individuality.

Self-portraits are perhaps the most complex type of portrait because the artist and sitter are the same person, and the image has a personal, diary-like feel. In his self-portraits Mapplethorpe experiments with different aspects of his identity. He presents himself in various ways from knife-wielding thug to transvestite.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1983, printed 2005)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2014

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1980, printed 1999)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2014

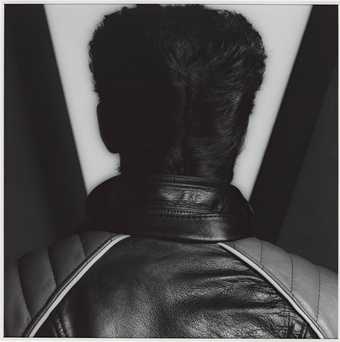

In the introduction to his publication Certain People: A Book of Portraits 14 1985, Mapplethorpe is quoted as saying that his self-portraits express the part of him that is most self-confident. The cover image Mapplethorpe chose for this publication is the work Self Portrait 1980. Here he portrays himself as the archetypal bad boy, with black leather jacket, dark shirt, cigarette hanging out of the corner of his mouth, cool gaze and edgy 1950s-style hair.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1980)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

The image reminds us of Hollywood icons James Dean in the film Rebel Without a Cause 1955 and Marlon Brando in The Wild Ones 1953. As in many of his portraits, Mapplethorpe poses facing the camera straight-on and his mouth is at the very centre of the photograph.

In 1986 Robert Mapplethorpe was diagnosed with AIDS, the syndrome caused by HIV. The HIV/AIDS pandemic was one of the most significant international events in the 1980s and affected the lives of many of Mapplethorpe’s friends and associates. At the time, most of those diagnosed with the disease did not survive more than two years. Mapplethorpe’s self portraiture towards the end of his life reflected his ill health, his search for release from his suffering, and his mortality.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1988)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

In Self Portrait 1988 Mapplethorpe is seated facing straight ahead, as if he is looking death in the face – confronting it straight on. The skull-headed cane that he holds in his right hand accentuates this. Mapplethorpe is wearing black, so that his head seems to float free, disembodied, surrounded by darkness. Using a very shallow dpeth of field, he photographs his head very slightly out of focus perhaps to suggest his gradual fading away. Robert Mapplethorpe, until the very end of his life, believed that he could beat AIDS.

What do you think? Portraits vs. self-portraits

Robert Mapplethorpe

Meredith Monk

(1985)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1975, printed 1997)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 2014

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1988)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

- How does a self-portrait differ from a standard portrait?

- Look at Mapplethorpe’s Self Portrait 1988. How does it differ from his earlier self-portraits?

- What elements of his own life does Mapplethorpe draw on in this work?

Balance and Harmony

Robert Mapplethorpe

Francesco Clemente

(1982)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1981, printed 1992)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Balance and harmony are key to Mapplethorpe’s photographs. Mapplethorpe consciously composes the images to emphasise their structure and geometry. In many of his portraits and self-portraits, the sitter is shown from the front and presented in perfect symmetry.

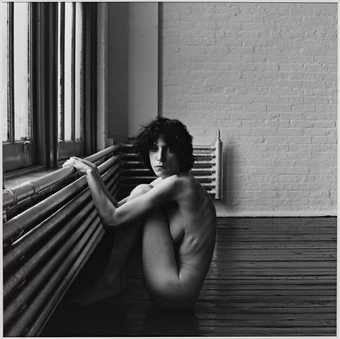

Mapplethorpe’s photograph Patti Smith 1976, like many of his photographs of Smith, is taken outside the studio. Captured while Smith temporarily lived in Mapplethorpe’s loft apartment, the photograph relies on natural light. Looking pensive and somewhat insecure she is curled up in a foetal position and holds onto a radiator pipe running along the wall. Although taken with no lighting, the careful structuring of the image is typically Mapplethorpe.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Patti Smith

(1976)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

The shapes of Smith’s body unify the geometries of the room and emphasize the perspective. The diagonals of the radiator pipes and of Smith’s arms and legs contrast with the otherwise horizontal and vertical structure of the image.

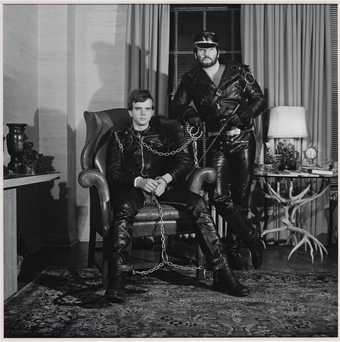

Censorship and Freedom of Expression

In the late 1970s, Mapplethorpe became increasingly interested in documenting his friends in the New York S&M scene. Often they were photographed nude, and sometimes shown involved in sexual acts. Shocking for their content and also remarkable for their technical mastery, the photographs placed him at the centre of debates around self expression and censorship in the arts. They tested the boundaries of creative freedom and have an important place in the history of artistic struggle to depict the world with honesty and truth. Mapplethorpe told ARTnews in late 1988:

I don’t like that particular word ‘shocking.’ I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before … I was in a position to take those pictures. I felt an obligation to do them.

Reaction to these images was divided. Some people were outraged, while others saw them as truthful explorations of the human body, sexuality and desire.

Robert Mapplethorpe

Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter

(1979)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

The culture wars

During the 1980s and early 1990s there was conflict between conservative and liberal groups. This is often referred to as the culture wars. Members of religious and conservative groups criticised artists for what they saw as their indecent, subversive and blasphemous work. Other prominent figures in art and popular culture, including the film director Martin Scorsese, artist Andres Serrano and pop star Madonna, were also debated in relation to this. Noticeably, all had been brought up as Catholics, and all questioned the church and religion through their art.

Religion

Mapplethorpe often used religious symbolism in his photographs. In Self Portrait 1983 he shows himself in battle dress (leather jacket), posing as a revolutionary figure, rifle in hand, in front of his sculpture Black Star 1983. Black Star consists of a black-painted frame in the shape of a pentagram (a five pointed star).

Robert Mapplethorpe

Self Portrait

(1983)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

The pentagram is shown with one point facing down and could therefore be interpreted as a symbol of the Devil. Mapplethorpe, who was brought up a devout Catholic, later liked to identify with the Devil because of his own ‘sinful’ behaviour. He once said that ‘beauty and the Devil are the same thing’.

Mapplethorpe also referenced religion in his portraits of others. In the work Lisa Lyon 1982 Lyon's pose reminds us of statues of Christ on the cross. The cross as a symbol appears in his work throughout his career, and many of his sculptures were in the shape of a cross.

I like the form of a cross, I like its proportions. I arrange things in a Catholic way.