Khadija Saye

Nak Bejjen (2017)

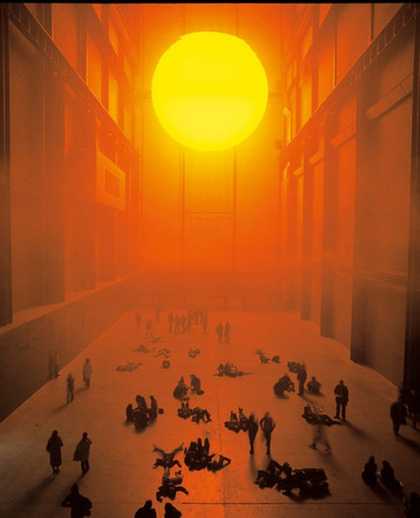

Tate

[music]

Pelumi Odubanjo: You are listening to Tate's podcast The Art Of … with me, Pelumi Odubanjo.

Shanelle Callaghan: And me Shanelle Callaghan. Pelumi is a multi-disciplinary artist, writer, and curator. His work centers around Black aesthetics and her relationship to historical imagery. She received the Forshaw Fine Art Endowment Award. Pelumi, that's such a great achievement. I'm proud of you.

Pelumi: Thank you so much Shanelle. While Shanelle is a photographic artist and curator, who’s practice looks at intersectional feminist critiques of race and gender, and according to one national newspaper was 2018 artists to watch. Basically, you're in the safest of hands.

This is a series telling the human stories behind art. In this episode, we are exploring the art of healing.

Kelechi: Dancing is prayer, it is movement it is meditation, but what we are finding is that when Black women dance is co-opted by the white gaze.

Nina: What I want with this series was to portray Black women in this position of power, and questioning who is on power, and who can change things?

Dawn: Despite the fact that trauma is much more spoken about than it used to be, I think sometimes there is a difficulty in naming certain experiences as being traumatic.

Pelumi: I think healing is a very personal journey more than anything. It's a very personal way of reckoning with the past.

[music]

Pelumi: Healing has never felt like a more pertinent term and our new ever-challenging world. With the search for personal healing, wellness, and alternative health practices, becoming one of the fastest-growing industries in the world.

I'm really interested in healing. As for me, healing is not only a way of recollecting and relieving oneself of a past-trauma, but also a process of embracing and reclaiming the power of the mind and body.

Shanelle: We're both a part of 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning's development programme, which supports emerging creators of colour into the creative and cultural industries.

[music]

Shanelle: The poet Pavana Reddy describes healing as an art, something that takes time, practice, and love. While the dictionary definition refers to healing as the process of becoming or making somebody or something healthy again.

Pelumi: Isn't seeking out a stronger, healthier, and more peaceful experience something everyone hopes for? I started getting into healing more when I decided to have a self care routine for my mental health. That led me to research the connection between Black women artists and self-care.

Shanelle: Art as healing is a central theme for many artists. From installations, photography, paintings, dance or performance art. The art of healing is something intimate to everyone.

Pelumi: Whether that is healing from past trauma by empowering yourself through performance, healing from personal vulnerabilities through self portraiture, or healing from the pain of historical wrongdoings.

Healing is a key theme explored by many artists, but can be particularly pertinent for those deemed on the margins of society. In this episode, we'll be exploring some artworks which show the power, pain, history, and freedom of healing.

One place where people come together for change and progress, the peaceful protest, our system producer, Deborah went down to the SARS protest in London to find out what healing means to some of the Black women in attendance.

Female Participant 1: A big thing, I guess for me on a psychological level is not having to inhabit your trauma.

Female Participant 2: I feel like healing is about wholeness. As a Black woman a lot of things are taken from us physically, mentally, spiritually.

Female Participant 3: We have experienced a lot of trauma as Black women, such as myself as big Black women. A lot of the things I've learned from myself have not just been from outside of my community. It's been within my community. Part of healing for me, is healing those traumas that have been passed down from my grandmother to my mother, to myself. I don't pass it down as well.

Female Participant 4: We've been told we're not beautiful enough, we've been told that we're not educated enough.

Female Participant 5: It can be confusing as to understand what exactly is wrong. Really, take some time out to focus on yourself, to understand your own self.

Female Participant 6: Allow yourself to feel fully human. That's something that I feel like as Black women, we're not given the opportunity to do it.

Female Participant 7: Speak to other Black women, I would say, have a community and try to lean on your community when you need it most.

[music]

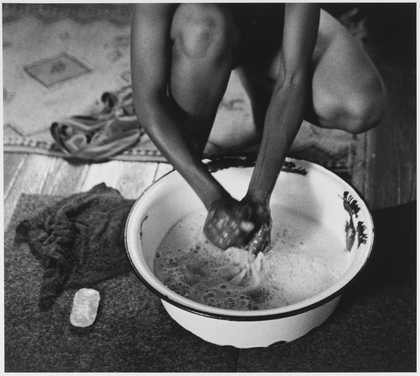

Pelumi: The first artwork on our journey in healing is Nak Bejjen by Khadija Saye. Saye was a Gambian-British photographer whose work was infused with themes of heritage, identity and the role of faith in healing. Nak Bejjen is part of the series Dwelling, in the Space We Breathe of which six images remain.

The other images were lost in the tragic Grenfell Fire in which Saye lost her life. In the image, the artist is shown in Black and white seated and wearing a dark fabric with her head covered and bound. Her head is bowed as if in prayer with a person's outstretched arm reaching into the frame, holding a horn like object to the nape of Saye's neck.

The poignant and delicate nature of self-healing is so integral to the piece. It is not only felt in the reading of the image, but it was also present in the process of making the series. As Aïcha Mehrez, an assistant curator at Tate Britain can tell us.

Aïcha Mehrez: The element healing in these works is present not only in the subject matter, but also in the physical process of the image-making. Through, Saye's decision to use a 19th-century photographic technique. She's choosing to surrender herself to not only a higher power spiritually, but a higher power in terms of image-making. In the catalogue for the Diaspora Pavilion, they say that the journey of making a wet plate collodion tintype is unique. No image can be replicated and the final outcome is beyond the creator's control. Within this process, you're surrendering yourself to the unknown, similar to what's required by all spiritual higher powers, surrendering, and sacrifice. Each tintype will have its own unique story to tell. The metaphor for individual human spiritual journey.

Before she made the series, she was involved in a traumatic episode personally. The photographs have this suggestion of self-healing. She's doing that through these imagined rituals.

They came about through this need for spiritual grounding, which she herself was working through. She's using herself as the subject in a lot of these works to engage really deeply and instinctively and personally with the way in which trauma is embodied in the Black experience.

She's looking at the processes or the objects that we turn to in life's most challenging moments.

Shanelle: The theme of process healing can also be finding creative practices outside the gallery walls as I found out, when I caught up with Dawn Estefan, a psychotherapist who addresses trauma through creative expression.

Dawn Estefan: I would say that any creative outlet that encourages self-expression or helps one to connect to another and provide healing is a great outlet for either creating therapy or therapeutic response to our self-expression.

Whether we're talking about writing poetry, sculpting and singing, art therapy in particular, which became popular in, I think, the 1940s, integrates psychotherapeutic techniques with the creative process and is rooted in the idea that creative expression can foster healing and good mental health.

Art therapy can be used to help people explore emotions, uncover and explore unconscious content, which in turn can help in the development of self-awareness, coping with stress based in self-esteem, and more importantly, promotes the development of emotional language and emotional narrative.

I've got a real love for storytelling and the listening and the telling of stories is central to Caribbean and African culture and I'm from the Caribbean. I became really fascinated and convinced by the belief that man could be saved by the power of the word.

I think as I continued the work, I really became interested in trauma and our understanding of trauma and how our body and our minds react to traumatic experiences. The fact that people could often go through life, not recognizing that they'd experienced the trauma or not naming it as such.

It's interesting to be asked, what do I think about Khadija Saye's work, specifically Nak Bejjen.

In terms of my areas of interest in how race, culture and spirituality can affect the mental health of people from Black communities.

I look at the picture and I wonder about the ceremony that's taking place and how things that are buried within our cultural identities bring healing to us in different ways, but how these practices are sometimes hidden because they are misunderstood by Western epistemologies or demonized as being ancient or primitive.

Shanelle: Chatting with Dawn really showed me there's a connection between the role of African spirituality and healing that is demonstrated in Nak Bejjen, but what do other people see when they experience Saye's work?

Nina Franco: When I look at the work of Nak Bejjen from Khadija, it brings me back home because I grew up in the Afro-Indigenous religion in Brazil. This is actually how we do some of the rituals, and for me it was very interesting to read the fact that Khadija is from this multi-cultural backgrounds, religions that are Muslim and Christians as well and how the objects used it in this work and totally related also to African religions, how she makes all of them of her identity and the objects in this image.

The way she places her body, it's like the elders. It's exactly this position. I have seen this in real life so many times and it's so calming, so comforting to my heart to my cities. I feel protected again.

Shanelle: That was Nina Franca and Afro-Brazilian artist whose work uses photography and installation to correlate social and political commentary with ancestry, memory and history. You'll hear more from Nina later.

Pelumi: Shanelle, what did Khadija Saye's work teach you about spirituality?

Shanelle: Khadija Saye's work taught me a lot actually, especially from talking to Dawn and Nina. It's interesting to hear from their perspectives about their work because they all came from different places within the Black diaspora.

Nina is Brazilian and Dawn is Caribbean. Despite coming from different parts of the diaspora, they both were able to connect with the familiarity of the images and spirituality references. The fact that she chose to focus on African spirituality is impactful because it makes people feel like it's okay to practice this religion despite the stigma.

Advert (Female speaker): Hey there, are you 16 to 25? Want £5 tickets to see exhibitions, free events, creative opportunities, and special discounts, join Tate Collective. Make sure you follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter too. All right. Bye for now.

[music]

Pelumi: The artist for our next piece uses scale, texture, humour, and hints of romance to look at how freedom from oppression is a clear route to healing. Turner prize award-winner Lubaina Himid celebrates the originality of Black women. Here is assistant curator Aïcha Mehrez to tell us more.

Aïcha: Her practice is a cornerstone of critical engagement with notions of British identity and Black British identity. This work in particular Freedom and Change, which was made in 1984 is a large mixed media installation.

The main body of work is painted onto a pink bed sheet and plywood and painted onto the sheet are two Black women moving dynamically across the painted surface. They're wearing dresses both women have got closely cropped short hair and wear Venus symbol earrings, which may suggest lesbian identification presenting the possibility of a romantic connection between the two.

The women could be interpreted as running barefoot or perhaps dancing, they're holding hands and the artist has said the device of placing two Black women in a painting together was an early method I used to counteract the assumption that there was only one story and that the Black woman never spoke.

One of the women's throwing her head back, maybe she's looking up to the heavens or laughing as she dances and the other woman gazes ahead holding the leashes for six black dogs, which are running ahead off the pink bedsheet into the space of the gallery.

Behind the women, there are the heads of two white men and the men are at ground level with only the heads appearing. Though the women don't appear to focus on the presence of these men with the ready cheeks, it may be that in galloping forward, they've kicked sand into the partially buried faces.

This scene was taken from a Pablo Picasso painting and Himid has appropriated that scene, replaced the white women with Black counterparts and the critic and curator Gilane Tawadros has said, that this citation from Picasso who's famous for drawing heavily from imagery of African tribal masks, reverses the modernist appropriation of primitive art and claims ownership of the process of gathering and reusing.

In doing this, she is drawing attention to the influences on white often male artists, which continue to go acknowledged, troubling the logic of the concept that in colonialisation, the coloniser dominates and improves a native culture, but in doing so she also creates a space for two Black women to surge forward and exist in the context only of their relationship to one another.

Pelumi: Seeking freedom from oppressive situations and finding healing in a supportive community feels universal and human. It's not surprising that Lubaina Himid would address it within her work. I caught up with Nina Franco who explored similar themes of political and social justice in response to contemporary events.

Nina: Looking through the work of Freedom and Change from Lubaina, what really takes my attention is the way in which the first Black woman is holding the second one, almost as if trying to push or carry her, like, "Come with me."

I see the first woman more as playing this role of, who's trying to set the other free and the other not having the energy so much. For me, it's also very interesting that they are walking or running through the coffee beans, which in South America they're mostly in Brazil. The beans is what is most remembered from slavery. They walk over the beans and they're Black women together are going to walk towards freedom.

Pelumi: Particularly with your Black iconography portraits, what drew you to make such images?

Nina: I wanted to create another case that was not the coloniser, the white male gaze of Black people, especially about Black women. As we know historically, the first sculptures were all made for queens and kings and intellectuals, important people in the society that they were always white.

What I wanted to do with this series was to portray Black women in these positions of power and in questioning who is in power and who can change things.

Shanelle: Pelumi, what did you learn from Lubaina Himid's work?

Pelumi: Himid's work taught me that healing in art is not only something which takes the form of the sorrowful or the spiritual even, but could also be depicted through humor and through subversion is best demonstrated of freedom and change. Himid uses multiple art-making techniques to focus on and reclaim issues of race, gender, migration and representations of the Black body, which aren't often seen in the Western Canon of art.

Seeing Himid's work, it brings hope to the way that I see the image personally of the Black female body in art. It's not something that I saw regularly when growing up and going to art galleries. Himid really brought a new perspective for me of what art can and should be.

Shanelle: That sounds really similar to Nina's work.

Pelumi: It really is similar to Nina's work. Nina, much like Himid, uses art as a way to, in ways, make visible what is often deemed invisible by again the Western canon of art. Franco uses art as a way to memorialize and pay homage to her community, which I find very inspiring.

[music]

Pelumi: For me as a Black woman, artist, and curator, one of the biggest ways I can look after myself was by surrounding myself with positive visions of people that look like me and my community, both past and present.

It was empowering, affirming, and healing. That's why I was excited to chat with Kelechi Okafor, a performer, athlete, public speaker, and owner of dance studio, Kelechnikoff. She uses movement, including pole dancing and twerk, as a tool of bodily empowerment.

[laughter]

Pelumi: Hi, Kelechi. Thank you so much for letting me visit your studio today in Peckham. I'm so excited to be here.

Kelechi Okafor: Glad you're here. Thank you.

Pelumi: What led you to establish a Black-owned fitness studio?

Kelechi: I was led to open the studio because of the ways that I thought that Black women specifically were ostracized within the fitness industry. When you think of fitness, you see white, very slim women, usually blonde, running around, laughing at salad.

When I would go to other studios, and I've taught at other studios, I just noticed how the general culture there just didn't allow space for anything other than whiteness, and I wanted something that differed from that.

I had experiences where I contacted a pole dance studio in Manchester, who credited Miley Cyrus as being one of the originators of twerk, to offer my services because I was teaching twerk workshops around the UK or I wanted to teach more of them at that point.

I sent a video of what a typical class would look like for me in the middle of the week. This white woman responded with, "I don't enjoy your style of twerk. I find it really basic. When me and my girls twerk, we put our knee pads on and we throw down."

Having those experiences, having those kind of visceral, envious, hateful responses to me, just wanting to realign the narrative about our histories, I think it's important for our stories to be told by us.

A lot of our art forms are repackaged and sold into the mainstream, they're whitewashed and then everybody else makes profit from it while we are simultaneously vilified for the things that we do.

That experience with the pole dance studio in Manchester, it went viral, picked up by a lot of Americans, a lot of Black American women, and they kept saying, "You should just open your own studio. Why don't you open your own studio?" That's the power I think of Black women, of Black sisterhood, where you can have a future imagined for you that you can step into boldly.

Shanelle: Dance can take many different forms and especially within art. However, for Black women, which is particularly in performance where the body takes center stage as a radical tool to heal.

Kelechi: Pole dancing and twerk definitely changed my relationship to my body because it made me interrogate and analyze the ways that Black women's bodies are hypersexualized within society and it's in teaching pole dance, with my knowledge of personal training, that I started to understand that this is how we emancipate ourselves from oppressive dynamics.

We have to reclaim what it means to pole dance. We can't ignore sex workers who have been doing this for centuries. I'm not even going to say decades. These things have been done, but we've been using our bodies in sensual and sexual ways for centuries.

We have to go back to owning our sensuality as well as our sexuality in a manner that suits us, that liberates us and that looks different for every person. Happened for me with twerk and pole dance. I realized that it could be a tool to help us all find our way back to our like divine feminine force.

Shanelle: Agostino Brunias’s Dancing in the West Indies was painted by the Italian born artists was based in Dominica between 1764 and 1796. It is the colourful but controversial piece naming for his highly romanticized and inaccurate portrayal of the lives of enslaved Africans who were depicted in the image dancing as they celebrate a pre-Lent carnival under the shadows of a generic West Indian plantation.

Pelumi: Kelechi, looking at this painting, what is your first reaction to seeing a painting such as this, which depicts Black women in such a historical manner?

Kelechi: I dislike it greatly. Viscerally, I just don't enjoy the painting. The first naked bodies we see dark skinned Black women. It's interesting to me that it's dark skinned Black women's bodies that are not afforded grace, they're not afforded care.

There's nothing obviously wrong with our natural naked bodies, but it's the fact that in this such painting, the sexual nature of it, is inflicted on the darker skinned Black women, where if the lighter skinned women get to wear their head wraps and be covered up and look joyous and having a great time.

To me, yes, dancing is prayer, it is movement, it is meditation, but what we are finding is that when Black women dance, it's co-opted by the white gaze. It's co-opted in a way that makes other people profit while we don't get to tell our own stories. I think that that is the importance of the time in history that we find ourselves to reclaim our narratives, to reclaim our bodies, and to reclaim our dance.

Shanelle: Some pieces of art are products of their time and how we interpret what they say about their subjects need to be viewed under critical lens.

Alice: I'm Alice Insley I'm the Assistant Curator of Historic British Art at Tate Britain, but I mainly focus on 18th-century art. It's an idealized image of what people wanted these plantations to appear like.

I think it speaks to a kind of benevolent slave ownership really where this is the sense of these are enslaved people enjoying themselves and having leisure time. It really doesn't acknowledge the violence and coercion that sat alongside that and would've been really prevalent. He's working at a time when the anti-slavery movement is becoming increasingly vocal.

This kind of image would've reinforced a pro-slavery idea that actually slaves were better looked after and enjoyed better conditions than, say the British poor, which was their really stock argument at the time. Trying to approach them critically is a way of trying to understand and think about those histories.

Also, how they continue to play out in the gallery, and what does it mean to show this image on the wall at Tate? How does it get interpreted and how are people experiencing it?

[music]

Shanelle: Our final piece on our journey of healing is a self-portrait by South African photographer Zanele Muholi. The photograph entitled Bona, is a part of the ongoing series, Somnyama Ngonyama. Meaning ‘hail the dark lioness’, and forms part of a new exhibition showcasing the artist's work at Tate modern.

Pelumi: The series began as a way for Muholi to document their presence in different spaces. Before becoming what the artist themselves describes as something unflinchingly personal, a statement of self-presentation through portraiture. This movement towards visual activism as a way of healing for the central theme to the artist's work is Peju Oshin, curator of Young People's Programme at Tate explains.

Peju: Photography in general, and thinking about how we document ourselves and we document our communities, there's always an element of performance to it. I think when we're thinking about this idea of self-portraiture, it is exactly as has been described. It is about you finally being able to control your own narrative around yourself. It is how you want to present yourself to the world.

There are so many ways in which when we sit down to pose for a photograph, we have this idea of how we want to be presented in the world.

That's finally a moment in which we feel really comfortable to do that, even if we hold some of those anxieties, doing that in front of an audience of friends or family. When you set up the tripod and you're in a room by yourself, that really feels like a moment of truth when you can really be at peace with yourself and heal.

Shanelle: Zanele Muholi's self-portrait, Bona, in Black and white, shows the artist with braided hair, lying with her back to the viewer, on a cream bedspread, which is pushed up against pattern cream patterns. Muholi had a circular mirror in which the viewer is able to see the artist's steady gaze.

Pelumi: For me, Bona is the work which confronts the long held ideas of what portraiture should be. As Peju and I discussed, Muholi's work is not only one of a personal representation, but really reflects the wider community. That being specific, a community of LGBTQ+ people living in South Africa.

Peju: It's really interesting to think about who the viewer is, because looking at Zanele Muholi's gaze in this image, they appear to be quite stern, or it’s described as being a penetrating one that forces people into dialogue.

I suppose, again, depending on who the viewer is, that's an important or interesting thing to look at, in terms of whether or not you are forced into that dialogue. I believe you don't have to be forced into a dialogue, when that's actually the dialogue that you want to be having, or it's a dialogue that feels really familiar to you.

It’s a really important image to have, when you're looking at self and thinking about these ideas of self-discovery. There are so many things that you travel or journey through, and there are so many changes that you experience from adolescence into adulthood.

This speaks to many people on many different levels, in thinking about those different stories and the ways that we can all meet an image and connect with it. Even if that isn't strictly what the narrative is, there was a point of entry for everyone, when looking at many of these works.

Shanelle: Bona connects me because of the level of vulnerability. I learned a lot from the discussion between Peju and Bona. When she was speaking about the gaze, it made me think about the ways that Black people are vulnerable, and how that should be seen a lot more in media or mainstream art, but it's not seen a lot or enough they’re either strong or victimized.

Pelumi: There is such a need to not only document but also archive as a means to redefine and also reclaim one's existence. I really get this vibe particularly when looking at the way that Blackness is depicted in Bona. The skin of Muholi's work, which is really laid bare for the audience to see - I really get a sense of pride not only in being Black but on a deeper level, just a pride in Blackness.

[music]

Pelumi: Hi Shanelle? How are you this morning?

Shanelle: I'm good, how are you?

Pelumi: I'm exhausted, as I think we both are, but we're both here and we're here to talk about The Art of Healing, literally The Art of Healing. What does healing mean to you?

Shanelle: I think healing means healing within yourself in your body and mentally because your mental health is connected to your body and maybe just finding different ways spiritually that can help you.

Pelumi: I wanted to ask you what have you learned from the process of this recording? From all the amazing people that you've spoken to.

Shanelle: I think just different insights of how different people work. It could be spirituality and how it connects to maybe therapy as well. Especially speaking to Dawn, she was very interesting. She brought, like, a different dynamic.

Pelumi: Is there an artist that comes to mind but we haven't actually spoken to but maybe just an artwork that comes to mind on this topic?

Shanelle: I think Christopher Hanson's painting called The Art of Healing is actually perfect. Christopher Hanson is a painter and he held his first solar exhibition called Music and Spirituality at 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning in 2018.

Quick facts about Christopher Hanson. He's of Trinidadian heritage. In his painting, The Art of Healing, the Black female protagonist in the image is carrying a spiritual cleansing ritual with a Black male lying down.

In the artist's own words he was able to create the ‘deepest portrait he's ever created spiritually depicting someone that can heal and placed in the power of such practice back into his community.’ Christopher purposely made the Black female subject to wear a white traditional African outfit because in Yoruba African tradition, white represents the height of spirituality.

Pelumi: Looking at the painting that you're speaking about, it just looks incredibly calming and I think it touches upon the amazing guests that we've spoken to so far. Just how healing for them is just an internal calming of the body and I definitely get that vibe from this piece that you've spoken about.

Shanelle: Is there any paintings from Christopher Hanson that you like?

Pelumi: A painting of his that stands out to me now as I speak to you, I think the painting’s called Mother.

[music]

A few more facts about Christopher Hanson. One Mother was commissioned for his mother by his mother and was the fifth time that the artist had attempted to paint her.

Two, it's extremely personal work for the artist with his mother being an ordained Orisha Priestess.

Three, the artist has said about his work, that he played with the colour palettes reminiscent of 15th Century Baroque painters such as Caravaggio and Velazquez, particularly in the ways that light and dark is used to highlight the physiological experience.

[music]

Pelumi: There were many spiritual, historical elements of healing which come into his work and I think what's also unique about this painting is the fact that the subject is an elderly Black woman. Obviously, it's not just a random Black woman.

It's the artist's mother, but there is something very special in seeing an elder Black woman depicted in this manner, depicted in portraiture because it's not necessarily that this isn't the case and that elder Black women don't want to sit for portraiture, but for some reason this image has been exempt from what we see, especially of classical art, but perhaps more so, it's making a comeback in contemporary art, which is where I think Hanson's work really crosses over to.

Shanelle: What does healing mean to you and what have you learned during this whole podcast process?

Pelumi: Thinking about what you said earlier Shanelle, about the different aspects or the different registers in which you could heal such as, through the spiritual, through an acknowledgement of trauma and through physical exercise such as dance. I think there are so many different aspects for healing.

I think healing is a very personal journey more than anything. It's a very personal way of reckoning with the past as a means to find maybe not a brighter future because that's quite cheesy, but maybe just to find a more content future for your personal well-being and I think what I've learned from all the amazing people that I've spoken to, from curators to dancers to artists is that again, healing can take many different forms and can be informed by many different concepts and I just found that so powerful to listen to and so powerful to be a part of.

[music]

If you want to discover some of the artwork we have been discussing in this episode up close and personal, the exhibition of Zanele Muholi's work will be shown at Tate Modern until March 2021 next year.

Shanelle: You have been listening to Tate's podcast The Art Of … with me Shanelle Callaghan and my wonderful co-host Pelumi Odubanjo. If you've enjoyed this episode, please rate review and subscribe so you don't miss out on new episodes.

Pelumi: This podcast has been part of Tate Exchange's year-long exploration of love. Check out @TateExchange on Instagram and Twitter to join the conversation.

This episode was a Stance Studios production for Tate, produced by Nicole Logan, Assistant Produced by Deborah Shorinde and Executive Produced by Crystal Genesis.

[music]

[00:36:47] [END OF AUDIO]

Black women always emerge as pioneers throughout history. From art, to science, to activism and sport, Black women are a force. Yet we live in a world where Black women are expected to be strong. They are expected to be support systems for others, to spearhead political movements, to jump three times as high. It can feel like the world is resting on their shoulders. So how do Black women find space and time to reflect and heal?

This episode of The Art Of ... explores how Black women and non-binary folk have used art and creativity as a caring space. It could be capturing and embracing healing rituals through photography, like Khadija Saye. It could also be carving out physical space for art therapy or pole dancing, where Black women and non-binary people can centre their minds and bodies. The episode presents the wealth of knowledge from Black women and non-binary people in taking care of themselves.

The Art of Healing is a Black female-led production. It is hosted and co-produced by Pelumi Odubanjo and Shanelle Callaghan, two young curators from The Factory programme at 198 Contemporary Arts & Learning - a Black-led gallery in Brixton. Hear the hosts chat with Kelechi Okafor, Dawn Estefan, Peju Oshin, Nina Franco, Aïcha Mehrez and Alice Insley.

This episode was a Stance Studios production for Tate Exchange and Tate Collective, produced by Nicole Logan, Shanelle Callaghan, Pelumi Odubanjo and Assistant Produced by Deborah Shorinde. Executive Produced by Crystal Genesis.

Want to listen to more of our podcasts? Subscribe on Acast, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or Spotify.