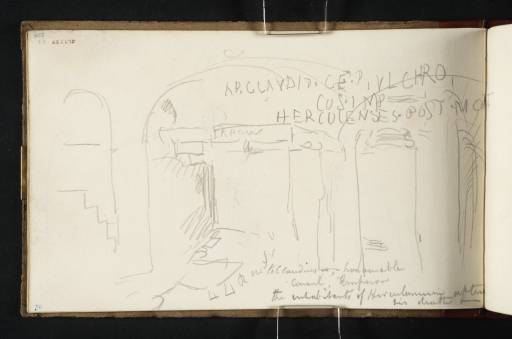

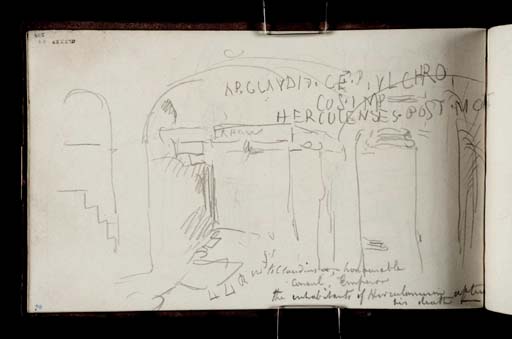

Joseph Mallord William Turner Inside the Theatre, Herculaneum, with the Pedestal of Appius Claudius Pulcher 1819

Image 1 of 2

Joseph Mallord William Turner,

Inside the Theatre, Herculaneum, with the Pedestal of Appius Claudius Pulcher

1819

Joseph Mallord William Turner 1775–1851

Folio 86 Recto:

Inside the Theatre, Herculaneum, with the Pedestal of Appius Claudius Pulcher 1819

D15896

Turner Bequest CLXXXV 84

Turner Bequest CLXXXV 84

Pencil on white wove paper, 113 x 189 mm

Inscribed by the artist in pencil with Latin text top right, see main catalogue entry, and ‘44 R[...]’ bottom centre

Inscribed by an unknown hand in pencil ‘to Claudius, honourable | Consul, Emperor | the inhabitants of Herculaneum after | his death–’ bottom right

Inscribed by ?John Ruskin in blue ink ‘278’ top left, inverted and ‘84’ bottom left, inverted

Stamped in black ‘CLXXXV 84’ top left, inverted

Inscribed by an unknown hand in pencil ‘to Claudius, honourable | Consul, Emperor | the inhabitants of Herculaneum after | his death–’ bottom right

Inscribed by ?John Ruskin in blue ink ‘278’ top left, inverted and ‘84’ bottom left, inverted

Stamped in black ‘CLXXXV 84’ top left, inverted

Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

References

1909

A.J. Finberg, A Complete Inventory of the Drawings of the Turner Bequest, London 1909, vol.I, p.550, as ‘Ruins, with an inscription, translated as follows (not in Turner’s handwriting) – “to Claudius, honorable Consul Emperor the inhabitants of Herculaneum after his death –.” ’.

1974

John Gage, ‘Turner and Stourhead: The Making of a Classicist’, Art Quarterly, vol.37, Spring 1974, p.87 note 52.

1984

Cecilia Powell, ‘Turner on Classic Ground: His Visits to Central and Southern Italy and Related Paintings and Drawings’, unpublished Ph.D thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London 1984, pp.187, 491 note 32, 496 note 82.

1987

Cecilia Powell, Turner in the South: Rome, Naples, Florence, New Haven and London 1987, pp.79 note 25, [82]–3 note 64.

Herculaneum, the ancient Roman town buried by volcanic lava during the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79, was discovered between the modern towns of Resina and Portici in 1709. Despite being identified before Pompeii, the archaeological exploration proceeded at a much slower pace and eighteenth-century activity was limited to underground tunnelling and the removal of objects by mine shafts which were frequently filled in again. Open-air excavations did not commence until 1828. When Turner visited the site in 1819, therefore, there was very little to see apart from a few passages below ground which tourists could only see in the company of a guide. Henry Coxe, for example, described the experience in A Picture of Italy, first published in 1815:

As all the openings to these subterranean ruins, one excepted, have been closed some time; it may be necessary the traveller should know that the officious Cicerone, who stands at this entrance should not be regarded: the money paid here might as well be thrown into the street; his curiosity will only be wearied with a perpetual sameness: he will be dragged up and down through damp, cold passages, without light or fresh air ... In fact there is little or nothing worth seeing, as the most magnificent works of art that have been brought to the light, are deposited in the Museum at Portici. The Theatre is the only object deserving of any notice.1

By the early nineteenth century, one of the few public buildings of note to have been discovered was the theatre which lies to the north of the main town.2 Buried under approximately ninety feet of volcanic matter, it had been partially excavated by digging channels into the rock and although its overall structure remained hidden, these openings offered snapshots of the semi-circular design, the tiered seating area, the stage and the orchestra. Turner would have visited these underground chambers by candlelight, and a similar tour was outlined by Sarah Atkins in her book, Relics of Antiquity, exhibited in the Ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum, first published 1825:

we descended by a spacious stone staircase of fifty steps, and were conveyed over the wall of a theatre, which presents one of the most perfect specimens of ancient architecture; but the darkness that reigns within it is too deep to be dispelled by the feeble glare of a few torches: its cunei [seats in the theatre] indeed receive a faint glimmering of daylight from the funnel over them; but the lava perpetually intervenes, and its magnificence can be discovered only by glimpses. Still it is a pleasure to descend into its dark and damp recesses, to trace its corridors, stage, orchestra and proscenium, and the seats of the consuls: far above the carriages of Portici are heard rolling over the spectator’s head, with a sound which has been sometimes described as resembling that of thunder; but this does not convey the idea, for it is a sound that cannot be expressed.3

Turner made a series of studies at Herculaneum, see folios 80 verso–87 (D15886–D15898; Turner Bequest CLXXXV 78a–85), and although it is difficult to pinpoint the individual locations, the majority, if not all, represent views of the theatre. The schematic nature of the drawings reflects the experience of sketching in the gloom of the subterranean passages. The location of this sketch can be identified from the Latin inscription, which as Cecilia Powell first noted, came from the theatre.4 Turner has transcribed the text ‘AP. CLAVDIO. CF.PVLCHRO | COS.IMP | HERCVLENSES. POST. MO[RT]’ from a pedestal found at the left (south-west) of the proscenium (stage) which once supported a statue of the consul, Appius Claudius Pulcher who built the theatre.5 As Turner’s study shows, the inscription could be seen in situ within a vaulted space hollowed out from the lava and rubble in which the theatre was buried. The pedestal is the square block at the centre of the composition.6

At the bottom of the page another person has provided an English explanation of the Latin dedication, ‘to Claudius, honourable | Consul, Emperor | the inhabitants of Herculaneum after | his death–’.7 The unknown author of the translation appears to be the same hand as that on a sketch of Virgil’s Tomb at Posillipo, see folio 70 (D15865; Turner Bequest CLXXXV 68).8 A further inscription relating to the theatre at Herculaneum appears on folio 85 verso (D15895; Turner Bequest CLXXXV 83a).

Nicola Moorby

November 2010

The theatre is outside of the present-day archaeological site of Herculaneum and is currently not open to the public. Virtual views in the eighteenth-century tunnels can be seen online at ‘Herculaneum Panoramas’, http://www.proxima-veritati.auckland.ac.nz/Herculaneum/ , accessed November 2010.

Sarah Atkins (later Lucy Wilson), Relics of Antiquity, exhibited in the Ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum, with an account of the destruction and recovery of those celebrated cities, London 1825, p.53.

Guide to Herculaneum Illustrated, Pompeii 1870, p.28. See also E.R. Barker, Buried Herculaneum, London 1908, p.186, Mary C. Sturgeon, ‘Dedications of Roman Theatres’, in Hesperia Supplements, vol.33, 2004, p.416, and the website of ‘Scavia archeologici di Ercolano’, http://www.ercolano.unina.it/fotoErcolano/tea_83.jpg , accessed November 2010.

Compare a nineteenth-century illustration of the chamber and the pedestal, after de Forio, ‘Part of the Stage of the Theatre’, reproduced in Barker 1908, between pp.40–1. See also a virtual panorama of the view at http://www.proxima-veritati.auckland.ac.nz/Herculaneum/split_node_pages/node_201.html , accessed November 2010.

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Inside the Theatre, Herculaneum, with the Pedestal of Appius Claudius Pulcher 1819 by Joseph Mallord William Turner’, catalogue entry, November 2010, in David Blayney Brown (ed.), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, Tate Research Publication, December 2012, https://www