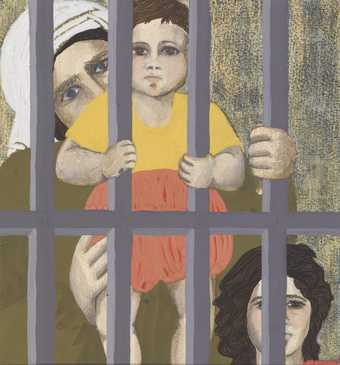

Gulsun Karamustafa

Prison Paintings 9

(1972)

Tate

A variety of circumstances have led to artists being isolated from society. Depending on the situation, a time of solitude can be welcome or uninvited. Artists may have to adapt their ways of working in order to continue making art. They may even need to explore whether being creative during such a time is possible.

Shakespeare allegedly wrote King Lear and several of his other masterpieces whilst isolated from society. There can be a pressure on us all to be creative during a time when we are distanced from the distractions of our normal lives. However, making art during a time of crisis can be a privilege. Not everyone is able to. Each experience of isolation is unique and artists express their creativity during these times in their own ways.

Read on to explore how artists within Tate’s collection have responded to making art in isolation. They are supplemented by perspectives from artists and associates of Tate Exchange, a place to ask questions about how society and art come together.

The Benefits of Solitude

Alfred Wallis

Voyage to Labrador

(?c.1935–6)

Tate

For some, isolation is a choice and a way to retreat from society to focus on making art. The painter Alfred Wallis was known for secluding himself in his St Ives home, where he would paint from memory. Many artists work in studios, places where their creativity can be fully realised. Having a dedicated space to make art whilst removed from social interaction can be a benefit to their practice.

Artists like Georgia O'Keeffe and Frida Kahlo are known for spending long periods of time in their studios. O'Keeffe spent four years restoring a 5,000 square foot compound in Abiquiu, New Mexico from the Spanish colonial era. The end result proved to be a significant inspiration to her practice.

Louise Bourgeois, known for her large-scale sculptures, gives an interesting perspective to solitude. Whilst her sculptures are often interventions in public spaces, the generation of her ideas often happens alone. The isolated space can be a source of inspiration.

‘Solitude, even prolonged solitude, can only be of very great benefit.’

Louise Bourgeois

Bruce Nauman’s Mapping the Studio II with color shift, flip, flop & flip/flop (Fat Chance John Cage) was created from material that suggested itself to the artist by chance.

'What triggered this piece were the mice. We had a big influx of field mice that summer in the house and in the studio ... They were so plentiful even the cat was getting bored with them ... I was sitting around the studio being frustrated because I didn’t have any new ideas, and I decided that you just have to work with what you’ve got. What I had was this cat and the mice, and I happened to have a video camera in the studio that had infrared capability. So I set it up and turned it on at night and let it run when I wasn’t there, just to see what I’d get ... I thought to myself why not make a map of the studio and its leftovers ... it might be interesting to let the animals, the cat and the mice, make the map of the studio. So I set the camera up in different locations around the studio where the mice tended to travel just to see what they would do amongst the remnants of the work.'

Bruce Nauman

Nauman generated nearly forty-two hours of footage that he edited and manipulated to create the final artwork, which is both comical and violent.

Yet for many, isolation is a condition imposed on them by geographical, political or biological factors. Anna Farley, an artist and neurodiversity activist, distinguishes between isolation and solitude by the freedom to choose:

'Isolation means I have the opportunity to distil what concerns me and what I want to make and do. I believe isolation is a chance for all artists to disrupt and evolve their practices, which constitute being a working contemporary artist in and out of the mainstream arts industries. I am autistic and isolation is a symptomatic issue for me, isolation is part of my life and consequently the question is one I constantly confront. This is not a choice. I think this typifies what the word means to me. Solitude is when I can make a decision to distance myself physically and mentally from external factors.'

Anna Farley

Farley acknowledges there can be benefits to isolation even when imposed. She writes during the 2020 COVID-19 imposed isolation in the UK:

'I am taking this time to engage in developing a space to make art and challenging myself to understand what a healthy work relationship is for me as an artist; not allowing art to totally consume me; experience where the boundaries are to maintain my personal health and give space to creativity.'

Anna Farley

Being creative with what you have

Nauman’s artwork came into fruition through his ability to see new possibilities with the resources he had access to. Throughout history, artists have been restricted with the spaces and materials available to them through government imposed sanctions.

During the Soviet era, artists working in Moscow had to resort to using their apartments for making and showing art, because their practice was not state approved. This became known as APTART. Artists including Vadmin Zakharov, Andrei Monastyrski and Ilya Kabakov were part of this practice. Irina Nakhova transformed her family’s apartment into a temporary installation, Room no.2, between 1983 and 1986.

Watch this film where Nakhova describes using her apartment as a canvas for her work.

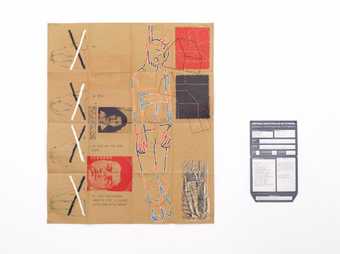

In 1973, Chile’s civilian government was overthrown and the country became a dictatorship. Eugenio Dittborn created his Airmail Paintings as a way of communicating with the outside world. They were designed to be folded and sent abroad. Dittborn compared them to sending a message in a bottle. When displayed in galleries, the artworks are accompanied by their envelopes on which is recorded the destination in which the work has been displayed.

Artists like Nakhova and Dittborn have had to adapt to imposed isolation. Jason Wilsher-Mills, a digital artist who creates interactive paintings and sculptures, speaks of his ability to adapt to working under isolation because his work is digital. When asked how he is creating under the COVID-19 crisis, he writes:

'Being disabled means that we are excellent at adapting and changing our practice, whether it may be due to illness, disability or in this case a global pandemic. My chair has become my studio, and my MacBook my meeting room. I have found that being a digital artist has proved somewhat of a bonus at this point, as I am well used to sharing and making work electronically, and being somewhat adaptable.'

Jason Wilsher-Mills

Both Nakhova and Dittborn worked alongside peers experiencing similar circumstances. Wilsher-Mills is a member of Shape Arts, a Tate Exchange associate that works to promote and support Disability-led arts. A sense of community can often balance feelings of isolation.

'Surround yourself ‘virtually’ with good, supportive people, and most important of all keep making art. It is so important to talk to others, to have a support network, and be able to admit that you need some further support.'

Jason Wilsher-Mills

Eugenio Dittborn

To Hang Airmail Painting No.5

(1984)

Tate

Finding Inspiration

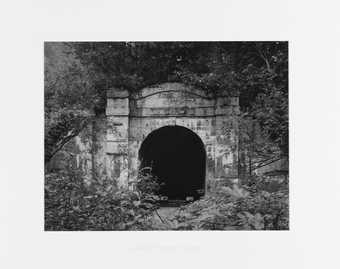

Mark Ruwedel

Virginia and Truckee #10

(1996)

Tate

Mark Ruwedel

Crater #6

(1999, printed 2008)

Tate

Mark Ruwedel

Great Northern #11

(2005)

Tate

Removed from society and the regular stimuli that might spark imagination, it can be inspiring to look to artists who have engaged with the enclosed spaces they isolate themselves in. Some artists, like Mark Ruwedel, have used remoteness as a theme in their work. He photographs locations like abandoned railway lines and deserts that have no signs of human life. This documentation of isolation and remoteness can become the subject.

Artist, Hamja Ahsan, talks about finding inspiration in the slowness that isolation brings. Retrospection and introversion can be powerful tools to reexamine why we become artists and continue a form of artistic practice whilst under lockdown.

'Life has slowed down. Perception is heightened. Tidying your room is a form of curatorial practice. I have revisited years of archives, photographs, past artworks stretching back to my childhood. I have curated a family photo album, paper curating an exhibition of my mum’s photographs from the 1960s and from her childhood.'

Hamja Ahsan

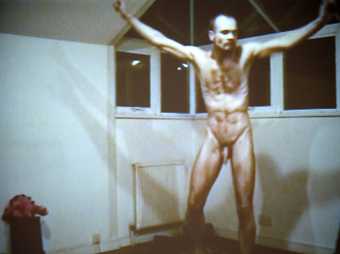

Our behaviour whilst alone can be a source of inspiration. In Sam Taylor-Johnson’s Brontosaurus, she films a man dancing naked in his bedroom to very fast techno-jungle music. In the finished film, she edits the footage so it is viewed in slow-motion. Taylor-Johnson films something that would normally take place in the public space, but the nakedness of her subject makes this a private act. By watching something that occurs in isolation, her audience become voyeurs. We are privy to something that resembles a private ritual, with the man oblivious to the camera and the fact he is being watched.

Sam Taylor-Johnson OBE

Brontosaurus

(1995)

Tate

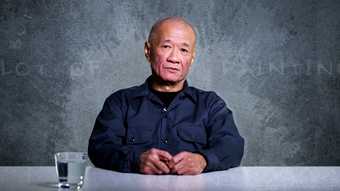

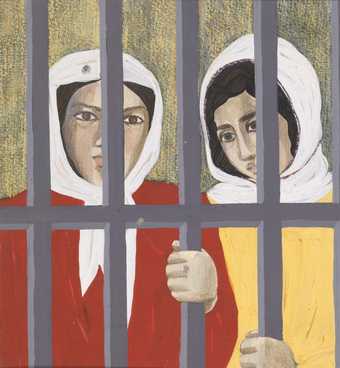

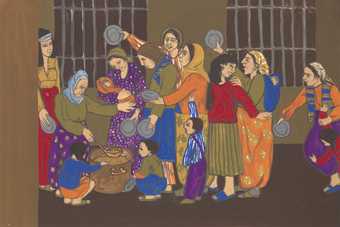

To find inspiration whilst in quarantine, we can look to artists who have created art whilst imprisoned. Gülsün Karamustafa was incarcerated in Turkey for aiding and abetting political activists after the military coup of 1971. Her Prison Paintings are a series of fifteen paintings that depict intimate and private moments in the lives of the prisoners and reflect Karamustafa’s personal observations of daily life in prison. She painted these from memory after being released.

‘I made them in order to remember, in order to be able to keep [what happened] in mind.’

Gülsün Karamustafa

Gulsun Karamustafa

Prison Paintings 16

(1972)

Tate

Gulsun Karamustafa

Prison Paintings 10

(1972)

Tate

Gulsun Karamustafa

Prison Paintings 6

(1972)

Tate

Gulsun Karamustafa

Prison Paintings 15

(1972)

Tate

Gulsun Karamustafa

Prison Paintings 9

(1972)

Tate

Gulsun Karamustafa

Prison Paintings 11

(1972)

Tate

Malangatana Ngwenya was imprisoned in 1964-65 whilst involved in the Liberation Front for Mozambique’s independence from Portugal. He produced many paintings in prison and this time of isolation during political unrest influenced many of his later works.

During World War II, the French artist Boris Taslitzky was sent to a concentration camp in Saint-Sulpice-la-Pointe where he painted frescoes on the walls of the cells and chapel. Later, he was transferred to the German concentration camp in Buchenwald, where he managed to steal paper and create portraits of his fellow prisoners. Ibrahim El-Salahi created drawings while he was imprisoned in the mid-1970s. He would sketch out plans for future paintings on the back of small cement casings, before burying them in the sand whenever a guard would come near. This led to the creation of The Inevitable.

Watch a film where El-Salahi discusses the process of having this idea whilst in prison and bringing it to fruition once released.

What does creativity under isolation look like?

Agnes Martin

Faraway Love

(1999)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Many of these artists were under considerable strain whilst in isolation and it raises questions about the pressure to be creative whilst in a crisis. Isolation can mean financial difficulty, restricted resources and an impact on mental health.

Throughout adulthood, Agnes Martin suffered from schizophrenia. Her quiet and serene paintings were in fact products of personal and spiritual struggle, which she recalled later in her account of this period The Untroubled Mind. In 1967, she sold her possessions and left New York, embarking on an eighteen-month journey around the United States and Canada in a pickup truck and camper van. She abandoned art making for over five years. In a letter to Leonore Tawney, Martin wrote:

‘I must give independence a trial. I will have to have more time.’

Agnes Martin

In 1972, she returned to making, producing a portfolio of thirty prints titled On a Clear Day. Perhaps spending time in isolation to rest and recover can be more beneficial for some.

Stephen Willats

Living with Practical Realities

(1978)

Tate

Much of the art that has been created whilst in isolation documents the feeling of solitude. This is something that has fascinated artists in and out of isolation.

Rosalind Nashashibi’s film, Vivian’s Garden, shows a mother and daughter living in isolation. Elisabeth Wild and her daughter Vivian Sutter shared a jungle garden in Guatemala. The home and garden are places of terror as well as healing, and the film outlines how, for example, a recent problem with a criminal neighbour caused the pair to be under curfew and threats, while catastrophic floods, kidnappers and fear of intruders are ever-present. On the other hand, they lead an idyllic life, making art in beautiful surroundings, living simply, being taken care of and taking care of each other.

Stephen Willats’s Living with Practical Realities gives an insight into the isolation of living in a tower block. Over six months, Williats photographed and interviewed Mrs Moran, an elderly lady living alone in the tower block.

Tehching Hsieh

One Year Performance1980-1981

(1980–1)

Tate

Documenting a period of isolation may resonate with others in unprecedented ways. To create something, in any form, can be art. For one year the performance artist Tehching Hsieh self-isolated himself, living in silence and not communicating with the outside world. This artwork is known as One Year Performance 1980-1981. Each hour he would punch a time clock and take a single picture of himself that resulted in an animation of his appearance changing over the course of the year.

What art under isolation looks like is up to you. Josh Rivers, creator and host of the podcast Busy Being Black, writes

'The advice I have for those who are creating their work, particularly that work that is rooted in the personal-political, is that our communities need you. We need each other always, but your voice, your art, your videos, your poetry, your music, your love, passion and even anger can help others feel less isolated, less alone, less uncertain. The only way we'll get through collective isolation is together, and art is such a powerful tool to help us through challenging times.'

Josh Rivers