Following his Occupations performance and the Heroic Symbols photographs documenting the action, as well as their related books Heroic Symbols and For Jean Genet, all of which were made in 1969, Anselm Kiefer continued to develop this theme in the medium of paint. Paintings based on the Heroic Symbols photographs were shown in the studios of the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe in 1970 as part of Kiefer’s final degree examination. These examination pieces were subsequently destroyed by the artist, but he did receive the ‘top grade’ for them after much furious debate.1 A number of the professors responsible for assessing his work in Karlsruhe were incensed by the photographs and paintings of Kiefer giving the Nazi salute, but the artist was supported by Peter Dreher, his long-time teacher, and the painter Rainer Küchenmeister, who had only recently been appointed as professor at Karlsruhe and who was a former internee of the Moringen youth concentration camp. Küchenmeister’s father, a communist journalist, had been executed as a member of the Rote Kapelle (Red Chapel) resistance group in 1943, and as such his son had more reason than most to despise the Sieg Heil salute and everything it represented. The fact that someone such as Küchenmeister saw something more than sheer provocation in the work that Kiefer showed in his examination exhibition is significant.

Fig.1

Anselm Kiefer

Untitled (Heroic Symbols) c.1969

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Anselm Kiefer

Between 1969 and 1971 Kiefer created a number of further oil paintings and watercolours featuring him giving the Sieg Heil salute in real and imaginary settings. These included a cycle of eight oil paintings from 1970, also entitled Heroic Symbols, which were only rediscovered by the artist in 2007 as he prepared to move his studio to Paris. In addition, he had created works such as Untitled (Heroic Symbols) c.1969 (fig.1), a watercolour, gouache and charcoal work on paper and the striking watercolour Everyone Stands Under His Own Dome of Heaven of 1970 (fig.2). In the former, using a photograph as a model, Kiefer painted himself rehearsing the ‘action’ in the stark landscape near Karlsruhe with a single skeletal tree for company. He stands directly confronting the viewer on a receding muddy path and behind a puddle that reflects the lower part of his body. It is another reference to the ‘walking on water’ visual joke that Kiefer had already played out in his Karlsruhe studio. Rather than presenting an epic biblical moment in which he walks on the Sea of Galilee, as depicted for instance by François Boucher in the Rococo painting Saint Peter Attempting to Walk on Water 1766 (Cathédrale Saint-Louis, Versailles), Kiefer’s Hitler ‘stand-in’ persona approaches a small puddle in a bleak setting, effectively deflating the pomposity and potency of the Sieg Heil gesture.

Fig.2

Anselm Kiefer

Everyone Stands Under His Own Dome of Heaven 1970

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Anselm Kiefer

With regard to Everyone Stands Under His Own Dome of Heaven, the title of which was inspired by a line in the unfinished novel The Man Without Qualities (1930–43) by the Austrian writer Robert Musil, the artist has denied that this painting explores fascism. He has argued instead for a theological context: ‘Each man has his own dome, his own perceptions, his own theories. There is no one god for all. Each man has his own, and sometimes [one person’s worldview] overlaps with or intersects another’s’.2 Kiefer has investigated the structures of different faiths throughout his career, but despite the artist’s explanations, the tiny, almost comically condensed figure who stands alone on a snow-dusted, tilled field in this painting is undeniably donning the same military coat that can be seen on the diminutive Hitler/Kiefer character in the Heroic Symbols photographs, books and the 1970 oil paintings.

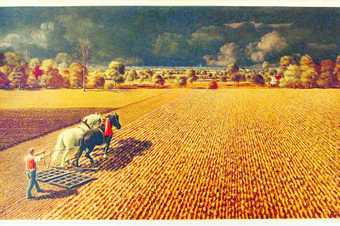

Fig.3

Werner Peiner

German Land (Deutsche Erde) 1933

The bleak landscape also alludes to a National Socialist visual context. The field with receding ploughed lines recalls Werner Peiner’s much-reproduced but now lost painting German Land 1933, a ‘Blut und Boden’ (‘Blood and Soil’) work that was shown in the Nazi Great German Art exhibitions at the Haus der Kunst in Munich (1937–44) (fig.3). Stark fields would appear in many of Kiefer’s landscape paintings from the early 1970s onwards (the so-called ‘scorched earth’ paintings) as he excavated and scrutinised the idea of Blut und Boden. Everyone Stands Under His Own Dome of Heaven has a lighter touch in the application of paint, and in this respect it relates to the contemporaneous painting Winter Landscape 1970 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), where blood flows from a severed head suspended in the dark sky onto the soil of a snow-blanketed field below, and the 1971 work Ice and Blood (Seattle Art Museum, Seattle), which appears to combine the blood-stained snowy field of Winter Landscape with the saluting figure from one of the Heroic Symbols paintings. In Everyone Stands Under His Own Dome of Heaven Kiefer’s Hitler-esque figure seems to be giving a salute captured in a kind of transparent hemisphere suggestive of an ideological bubble or microcosm. The hemisphere is reminiscent of toy snow domes, relating this work to the witty and unsettling sense of child’s play mocking imperialist ambition that pervaded so much of Kiefer’s art during the first decade of his career.

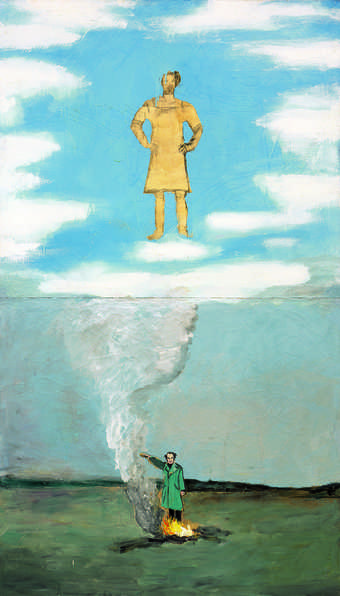

Fig.4

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbol I (Heroisches Sinnbild I) 1969–70

Oil and charcoal on linen

2605 x 1500 mm

Würth Collection, Künzelsau

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Würth Collection

The eight Heroic Symbols oil paintings have a different effect to the related artist books due primarily to the factors of scale, colour and the dreamy surrealist treatment of the subject, although it is true that many of the photographs used in the books also possess an ethereal quality. For the paintings, Kiefer combined photographic sources from the books for inspiration. Heroic Symbol I 1969–70, which the artist started working on in 1969 while still a student in Karlsruhe, shows the artist giving the Sieg Heil in a barren landscape by a burning fire or pyre (fig.4), and the pyre is a motif that recurs in many of his later artworks. As Kiefer has remarked: ‘There is always the distant memory of an ancient fire that creates and destroys. Everything comes from and returns to fire. It is as powerful as time’.3 In Heroic Symbol I the frontal saluting Kiefer figure is standing so close to the flames that the moment could almost be the beginning of an act of self-immolation. The painting seems to be divided horizontally, with the smoke of the lower section drifting into the celestial clouds of the upper half. The saluting form has become transfigured into an apparition of a transvestite wearing a white nightdress with his hands on hips, a cross-dressing parody of a Nordic god. The transvestite figure relates to photographs that Kiefer took of himself for the book For Jean Genet in which he donned both a white nightgown and a crocheted dress.

Fig.5

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbol II (Heroisches Sinnbild II) 1970

Würth Collection, Künzelsau

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Würth Collection

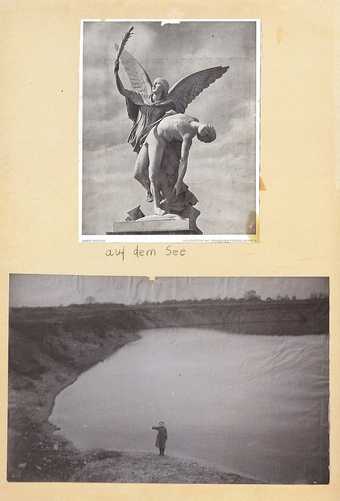

Heroic Symbol II (fig.5) imaginatively fuses two elements already present in the Heroic Symbols book (fig.6), namely a Nazi magazine photograph of August Wredow’s neoclassical sculpture Nike Carrying a Fallen Warrior up to Olympus 1857, a sculpture much admired by the National Socialists that can be found adorning the Schloßbrücke in Berlin-Mitte and one of Kiefer’s original photographs of himself giving the Sieg Heil by a lake, which in the painting is positioned in such a way that he appears to be saluting Nike.

Fig.6

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbols (Heroische Sinnbilder) 1969 (p.20)

© Anselm Kiefer

The Greek personification of victory also appears in Heroic Symbol V 1970 (fig.7) with Kiefer’s painterly rendition of Nike Crowning the Victor 1853, a statue by Friedrich Drake that can also be found on the Schloßbrücke.4 In Heroic Symbol V the pedestalled figure of Nike Crowning the Victor appears directly above the saluting Kiefer, who is standing on the banks of the river, clearly an image lifted from one of the Rhine photographs that he took of the Occupations performance and included in the Heroic Symbols book project.

Fig.7

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbol V (Heroisches Sinnbild V) 1970

Würth Collection, Künzelsau

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Würth Collection

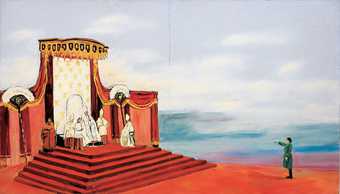

Heroic Symbol III is an oil painting on burlap that recalls the horizontal format, silvery-grey tones and elegiac mood of Kiefer’s Rhine photographs in Heroic Symbols, but as Kiefer is by the seashore the location is likely to be Sète in France, which also appears in the photographic series. Heroic Symbol IV is based on a photograph taken in Küsnacht, Switzerland, whereas the left panel of the semi-abstract foreground of Heroic Symbol VI makes the location harder to determine. The larger right panel of this work, which again seems to be horizontally subdivided, is abstract and dotted with red marks that could represent blood drops, relating it to Winter Landscape and later canvases such as Varus 1976. Heroic Symbol VII is very different again and has an almost pastoral Romantic quality, depicting Kiefer wearing jodhpurs and riding boots and saluting on a hill that overlooks a lush green valley. Finally, Heroic Symbol VIII (fig.8) is perhaps the most outlandish and critical of all the works in this cycle, a painting in which the saluting figure stands before an enthroned Pope Pius XII, a controversial individual due to the fact that he maintained a public front of indifference and remained silent while German atrocities were committed during the Second World War. It is a work that distantly recalls the Heinrich Riebesehl photograph of Joseph Beuys saluting with his right hand while holding a crucifix in his left, an image that could also suggest Church compliance to the fascist regime. There is little doubt that Kiefer’s painting would have greatly upset clerics in the Catholic Church had it been shown in the period in which it was made, and the work still maintains some shock value, although the scene seems truly preposterous, as is heightened by the Day-Glo colours that the artist used to render the scene.

Fig.8

Anselm Kiefer

Heroic Symbol VIII (Heroisches Sinnbild VIII) 1970

Würth Collection, Künzelsau

© Anselm Kiefer

Photo: Würth Collection

Fig.9

Anselm Kiefer

Palm Sunday (Palmsonntag) 2006

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

© Anselm Kiefer

While Kiefer’s work has dealt less with Catholicism than Jewish mysticism there are certain works created throughout his career, such as Father, Son, and Holy Ghost 1973 (Collection Sanders, Amsterdam) and Tate’s Palm Sunday 2006 (Tate AR00038; fig.9), which reveal his Catholic roots.5 Palm Sunday refers to the Biblical story of Christ’s journey into Jerusalem when worshippers laid palm leaves in his path, but while the fallen palm (a thirty-foot-long fiberglass and resin reproduction of an uprooted palm tree) may suggest themes of mortality and renewal, it signifies on a personal level the artist’s lapsed Catholicism and more generally the problems that have beset the Catholic Church. Kiefer can still recite the Latin mass, and the words of ‘Ave Maria’, and snippets of the Latin Mass can be found on the panels of palm fronds and stems that sit on the walls on either side of the tree.

In 1971 Kiefer attempted to show some of the Heroic Symbols oil paintings at the Ausstellung des Deutschen Künstlerbundes (in English the Exhibition of the Association of German Artists) in Stuttgart, but the artworks were rejected.6 They may have been returned to him because these artistic representations of the Sieg Heil salute were judged to have crossed a red line, irrespective of whether or not they could be appreciated as ‘ironic’. In 1973 the painting Heroic Symbol II was reproduced in the catalogue to an important exhibition series 14 mal 14 at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, a series that ran from 1968 to 1973, which had also promoted the work of Gerhard Richter, Georg Baselitz, Markus Lüpertz and other key figures of the post-1945 German art scene. The director of this gallery at the time was Klaus Gallwitz, the curator who was later responsible for the infamous German Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1980, an event that unleashed a storm of controversy concerning the installation of work by Baselitz and Kiefer.7 Gallwitz has stated that Heroic Symbol II was shown in 1973 at Baden-Baden, but the artist is sure that it was not displayed in the exhibition even though it was reproduced in the 14 mal 14 catalogue.8

Three paintings from the cycle were exhibited in Switzerland at the Kunsthalle Bern in 1978, as were the books Heroic Symbols I, Heroic Symbols II and For Jean Genet, along with forty-two other books Kiefer created between 1969 and 1978.9 However, the paintings were not seen again in public for another thirty years after 1978, and they were eventually found in poor condition in an industrial container in Kiefer’s studio complex in Barjac. Kiefer and Heiner Bastian, the dealer, curator, art consultant and one-time private secretary to Joseph Beuys, had the works carefully restored, a process that took nearly one year. The artist then stipulated that any exhibition of the paintings should only take place in Berlin and that they should not be sold individually or to a private collector, and further that the paintings should remain in Germany. Kiefer has stated that he did not want them to acquire any kind of investment value as ‘radical chic’.10

In 2008 Bastian staged an exhibition of the rediscovered Kiefer oil paintings and a display of the three 1969 artist books Heroic Symbols I, Heroic Symbols II and For Jean Genet at Galerie Bastian in Berlin Mitte. This exhibition was simply titled Heroische Sinnbilder (Heroic Symbols). Some thirty-eight years after the paintings were first made, they received their first public showing in Germany.11 The paintings were later acquired by the Museum Würth, which is located in Künzelsau, Baden-Württemberg, in south central Germany.