Photography was one of the key inventions of the nineteenth century; an extraordinary new technique of prime importance both to art and to science, that promised to transform perceptions of the universe itself, from the stars in its skies to the shells on its shores, and its flora and fauna in all their diversity. Not least, the likeness of human beings and their haunts could now be captured with unprecedented ease and speed. Just a few weeks before the holiday at Ramsgate that inspired Dyce to paint Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60 (Tate N01407), a correspondent to the Photographic News described the town as nothing less than ‘a paradise of photographers … It appears to be as much the custom for the ladies who are staying here to have their portraits taken as to take a bath’; photographers’ shops ‘abound’.1 While such use of the camera was essentially commercial, complementing Ramsgate’s donkey rides and other tourist delights, it is surely worth noting also that in September 1860, just a few months after Dyce exhibited Pegwell Bay, the photographer Arthur Henry Wall, writing in the same journal, recommended Pegwell as a place where his colleagues might seek the ‘picturesque’; what he called ‘not merely the form, but the very soul of nature, that spiritual beauty, which, although invisible to the coarse-minded, and uneducated, yet speaks audibly to each and to all’, and thereby makes the viewer ‘feel the present Deity’.2

From this point of view, the accusation by contemporary critics that Dyce had painted Pegwell Bay from photographs by no means disqualifies – and perhaps even suggests – the possibility of spiritual and even Christian meaning in its imagery. Yet in a sense it does not matter whether Dyce actually used a photograph or photographs to paint this picture; rather, we should perhaps consider how and why, in the 1850s, even as photographers aspired to ‘art’, a painter such as Dyce was seeking to evoke a particular place at a particular ‘moment in time’, the task being associated ever more closely with the camera. In trying to understand the relationship between painting and photography in the 1850s, we need, after all, to remember that this decade is regarded, according to historian of photography John Hannavy, as ‘the most important … in the establishment of photography in both Europe and America’, when ‘some of the finest photography of the Victorian era’ was produced, that captured the ‘instant’ and the ‘detail’ with ever more skill and ingenuity.3

Following the invention of photography in 1839 by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in France and Henry Fox Talbot in Britain – a sequel to experiments already in the 1800s by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, Humphrey Davy and others to ‘fix’ the action of light – Talbot’s ‘calotype’ process had come to the fore at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, and it stole the show in turn at the first ever dedicated photographic exhibition, held at the Royal Society of Arts in London in 1852. In contrast to Daguerre’s silvered plates, which produced unique images, the calotype used sensitised paper and enabled multiple prints. It was thus far more versatile, even though the paper’s fibres typically created ‘Rembrandtesque’ effects in place of Daguerre’s precision. Successive refinements of the calotype were, however, in turn trumped by collodion photography, which used glass instead of paper as the negative support, and thereby allowed not only sharper detail but also much faster exposure times. ‘On the prepared plate of Daguerre and on the sensitive paper of Fox Talbot’, wrote Dyce’s friend Lady Eastlake in 1857, the sun ‘concentrates his gaze for a few earnest minutes’, but

at the delicate film of collodion … he literally does no more than wink his eye, tracing in that moment, with a detail and precision beyond all human power, the glory of the heavens, the wonders of the deep, the fall, not of the avalanche, but of the apple, the most fleeting smile of the babe, and the most vehement action of the man.4

Examples of the new collodion processes – both ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ – were discussed in the photographic journals that now began to proliferate both in Britain and abroad (such as the Photographic News), and they were also prominent in the exhibitions mounted by the new photographic societies that emerged internationally during this the period. The latter included the Photographic Society of London (later Royal Photographic Society), whose first President was Sir Charles Eastlake and whose activities were eagerly supported by its patrons Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

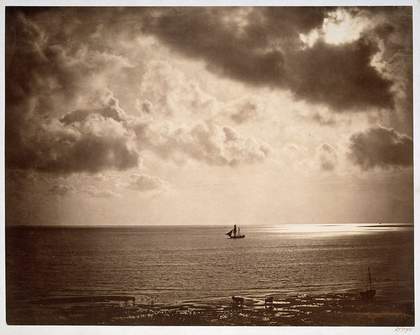

Fig.1

Gustave Le Gray

The Brig (or Sea and Sky) 1856

Albumen print from collodion-on-glass negative

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

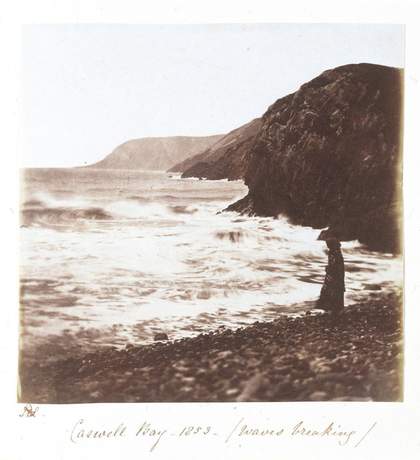

Fig.2

John Dilwyn Llewellyn

Caswell Bay – 1853 – Waves Breaking 1853

Salted paper print from collodion-on-glass negative

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Eastlake’s new role expressly associated the camera with art, for he was also President of the Royal Academy, as well as Secretary of the Royal Fine Arts Commission, the body overseeing the mural decoration by Dyce and other artists of the new Palace of Westminster. Dyce himself, meanwhile, had regular contact with key members of the Edinburgh Calotype Club, one of the leading pioneer photographic circles. This included John Cay, the brother of Robert Dundas Cay, who was Dyce’s brother-in-law, and a close friend of William Henry Fox Talbot, the inventor of the calotype. And in 1857, the year both of Lady Eastlake’s article on photography and Dyce’s first visit to Pegwell Bay, the association of art and photography itself came into sharp new focus. For it was in this year that the French photographer Gustave Le Gray’s The Brig (also known as Sea and Sky) 1856 (fig.1) was shown in the fine art context of the Art Treasures of Great Britain exhibition in Manchester. Taken the previous year, and acclaimed as ‘the finest photograph yet produced’,5 this image was created using moonlight for exposure, and from a single negative.6 Furthermore, Le Gray was adept at seizing clouds by looking into the sun, so that their forms, silhouetted against the light, became solid enough to register in the photograph. And like John Dilwyn Llewellyn in Britain, he had also succeeded in photographing breaking waves; those emblems of transience whose action Ruskin himself had despaired of ever ‘catching’.7 All of this now trod firmly on ground hitherto reserved for art.

Llewellyn’s wave photographs of the early 1850s, such as Caswell Bay – 1853 – Waves Breaking 1853 (fig.2), were made with a special camera shutter that captured movement of around 1/25th of a second, and had been hailed as of ‘immense use to the artist’8 – still not art itself, but a substitute for an artist’s sketch. But Le Gray – who like many early photographers had trained as an artist – had asserted that ‘It is my deepest wish that photography, instead of falling within the domain of industry, of commerce, will be included among the arts. That is its sole, true place’.9 His images, by implication, were conceived as art, the logical development of his training as a painter. When photography was finally admitted as fine art at the French Salon in 1859, the poet Charles Baudelaire’s disgust might almost be a direct riposte to Le Gray: photography, he argued, should ‘return to its true duty, which is to be the servant of the sciences and arts, but the very humble servant, like printing or shorthand, which have neither created nor supplemented literature’.10 Both Ruskin and Lady Eastlake took a similar position in Britain, arguing that photography could serve as artist’s sketch, and even an artist’s tool, but not as art in itself.11

Fig.3

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

Shells and Fossils 1839

Daguerrotype

Musée des Arts et Metiers, Paris

However, as the new collodion methods shortened exposures, motifs embracing sea, coast and sky became a prime attraction to photographers keen to demonstrate their expertise, and the Scottish photographer George Washington Wilson was reported in 1858 by fellow photographer Thomas Sutton as having rendered ‘clouds, ships, breaking waves, and a wet beach’ in an untouched, ‘legitimate’ daytime photograph.12 Dyce, in other words, was tackling in Pegwell Bay the very kind of motif with which photographers were seeking to rival art; hence, clearly, the aforementioned Photographic News article of 1860 that drew attention to Pegwell Bay as ‘picturesque’. Equally, Dyce’s lovingly detailed seashells in Pegwell Bay, in the basket held by Isabella Brand and on the shore, his cliff embedded with fossils, and his figures in rough woollen garments, were all motifs in which photography was widely felt to surpass the capabilities of art. Whether using paper, metal or glass as a support, the photograph was seen to excel in capturing surface ‘roughness’ and texture. Daguerre had photographed Shells and Fossils already in 1839 (fig.3) – hence, no doubt, the complaint of the critic Tom Taylor that Dyce had ‘turned himself into a daguerrotyping apparatus’13 – while Lady Eastlake had noted that ‘the forte of the camera lies in the imitation of one surface only, and that of a rough and broken kind … a face of rugged rock … the texture of the sea-worn shell … the fustian jacket’.14 It is as though Dyce in Pegwell Bay attempted to demonstrate that art can equal and even surpass photography; his chosen moment – evening – was certainly when light was most amenable to successful photography, just as his record of Donati’s comet in the sky realises what the photographic press had encouraged its readers to attempt.15

Fig.4

George Washington Wilson

Uncatalogued photograph of Kincraig Point, Elie 1853–1908

From glass plate negative

Aberdeen University Library, Aberdeen

© University of Aberdeen

Fig.5

William Dyce

The Man of Sorrows c.1860

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

Fig.6

George Washington Wilson

Untitled

Uncatalogued photograph from glass plate negative

Aberdeen University Library, Aberdeen

© University of Aberdeen

No photographs have come to light that correspond precisely, either in whole or part, with Dyce’s imagery, although the effect of fingers of pebbly beach reaching between bands of reflective water in the foreground of Pegwell Bay is very similar to that captured by his friend the photographer George Washington Wilson in Fife (see the uncatalogued photograph of Kincraig Point, Elie 1853–1908; fig.4), just as the rock-strewn landscape and contour of the hills in Dyce’s Man of Sorrows c.1860 (fig.5) have many similarities with photographs by Wilson of Glencoe (see, for instance, Wilson’s untitled, undated stereoscopic photograph, fig.6). However, Wilson recorded after Dyce’s death that his (Wilson’s) photograph of a Highland boatman had been translated into paint in Dyce’s Highland Ferryman 1857 (Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums, Aberdeen), and the topographically inaccurate background of that painting with its luminous, misty effect could reflect the kind of combination photograph, made by joining two separate negatives, that was used to overcome the differential exposure times of sky and land.16 That Dyce had more complex motives in mind in Pegwell Bay than simply to ‘copy’ or rival photography is surely suggested, however, by his friendship with the pioneer photographer David Octavius Hill. He had said to the latter as early as 1846 that ‘a trip to Rome with your Kulotype [sic] machinery would prove a profitable one to you’, but he had also expressed to Hill the desire to ‘have a lesson from you in your art. There is a terrace on the top of my house admirably suited for the purpose – and I think great use might be made of the proofs in preparing studies of drapery etc’.17 With her striped shawl and basket, the figure at the right in Pegwell Bay – Isabella Brand – certainly bears a resemblance to the stocky fishwives in their striped clothing which Hill had photographed with Robert Adamson at Newhaven (see Aberdeen Fishwife (Mrs. Flucker Of Newhaven, Shucking Oysters) 1845; fig.7). We might note in this context that Dyce’s 1856 portrait of his wife wearing silk and satin finery (Aberdeen Art Gallery, Aberdeen) had clearly celebrated his father-in-law’s occupation as a wealthy English trader in luxury cloths,18 and in Pegwell Bay, the artist would similarly seem to have used clothing for symbolic reference, this time to his Scottish photographer friends’ evocative transformation of life into art at Newhaven. Both Dyce’s description of photography as ‘art’, and the way he added only as an afterthought the comment that calotypes might serve as ‘studies’, certainly imply that he saw painting and photography as having common goals.

Fig.7

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson

Aberdeen Fishwife (Mrs. Flucker Of Newhaven, Shucking Oysters) 1845

Calotype

Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

Given Dyce’s spiritual outlook and polymathic character, we can thus perhaps view Pegwell Bay as a vision of art and science in symbolic union; the instant (5 October 1858) fused with the infinite (the sea and sky), to suggest the divine harmony that Dyce also sought in publishing musical motets, and in murals such as Religion: The Vision of Sir Galahad and his Company, created in 1851 at the Palace of Westminster, London. His inaugural lecture as Professor of Fine Art at King’s College, London, had dealt with ‘the Science of Fine Art’, arguing that ‘scientific’ attention to detail was an essential part of an artist’s vision of the beauty of God’s creation.19 Likewise, Dyce sought at Westminster to interpret Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur (1485) in an ‘allegorical’ manner, where the visible signified the moral or metaphysical.20 We might thus see the ‘photographic’ elements in Pegwell Bay as actually the vital means whereby he sought to capture ‘soul’, ‘spirit’ and even ‘Deity’ – the things the Photographic News urged photographers to seek at Pegwell Bay, as a ‘picturesque’ place. Dyce, after all, was a committed Tractarian and subscribed to churchman and poet John Keble’s view that ‘There is a book, who runs may read … Two worlds are ours: ’tis only Sin / Forbids us to descry / The mystic heaven and earth within / Plain as the sea and sky … Give me a heart to find out Thee / And read Thee everywhere’.21 His ‘photographic’ details in Pegwell Bay – whether breaking wave or textured shell – can be regarded as ciphers of the divine; ways, in his terms, to ‘distil the eternal from the transitory’.22