Fig.1

Participants in Tate Modern’s Summer Institute mapping connections between works shown in the History, Memory, Society suite, 2002

© Helen Charman

The eclectic and inclusive nature of art making today poses a number of challenges for teachers who wish to extend their art curriculum in schools to encompass contemporary visual art. These range from practical concerns such as the availability of resources, multimedia training and appropriate classroom/studio space, to subject-related questions about meaning-making and the value of contemporary visual art in contributing to the art curriculum and to pupils’ lives. This paper argues that in order to support teachers in expanding their curricula, it is necessary to teach the skills of interpretation to pupils. It explores the particular challenges posed by the process of interpretation in contemporary visual art as evidenced through an action research project undertaken at Tate Modern’s Summer Institute for Teachers in 2002. For the purposes of the paper, the field of contemporary visual art is seen, in the words of Linda Weintraub, as one from which, ‘No topic, no medium, no process, no intention, no professional protocols, and no aesthetic principles are exempt.’1 To this we would add that the work of contemporary visual artists is as much defined by their ideas as by their media. As such, being able to engage with these ideas is as important as knowing how to manipulate media. While debates around the value and character of interpretation are familiar to the language and practice of contemporary art, and the disciplines of art history and art criticism, they are yet to find a place in the school art and design curriculum.

The Schools Programme at Tate Modern is premised on the belief that there is an intimate relationship between interpreting art and making art. The displays from Tate’s collection offer pupils hundreds of ideas made manifest through material means. If pupils are to have a meaningful encounter with these works they need to know how to look at and interpret them in order to engage with these ideas.2 New research by the National Foundation for Educational Research, commissioned by the Arts Council of England and Tate, suggests that ‘it may be appropriate to reconsider the balance between developing art skills … and the distinct opportunities for intellectual challenge afforded by the study of art’.3 It seems, however, that scant attention is paid to interpretation as a fundamental component within pupils’ visual arts education. Instead, classroom practice in visual art takes as its dominant vocabulary the formal language of art making – of line, shape and colour – in which the teaching of practical skills dominates. Teaching practical skills, particularly those gained through experimenting with a range of different media, is integral to visual arts education, especially when working with contemporary visual art with its infinite variety of materials and processes. However, there needs to be a concomitant regard to the vocabulary of interpretation, exploration and expression of idea. Artists are inveterate cultural borrowers who harvest ideas from the whole realm of human experience. A visual artist encountering a work of art will look to see if there is anything of use for their own practice, be it in terms of process, idea, material or tendency. Those pupils who are in the formative stages of their identity as artists should also be able to make use of the content, as well as the form of contemporary visual art in order to enrich their own art work. And for those pupils who do not become artists, the skill of interpretation is equally necessary as a tool to negotiate our world of visual complexity and richness.

Philosophical arguments can also be made for the importance of interpretation more broadly in pupils’ lives. At the beginning of his essay ‘Fact, Explanation and Expertise’ philosopher Alasdair Macintyre tackles the problem of a world without interpretation, the experience of which could only be recounted through literal sensory description: this is what I see; this is what I feel, touch, taste; this is what I hear.4 A world in which the stars would be but many small light patches against a dark surface. If all our experience were to be characterised exclusively as sensory data (which Macintyre acknowledges is a type of description useful for a variety of special purposes), then we would be confronted by a world which is ‘a world of textures, shapes, smells, sensations, sounds and nothing more’. Crucially, such a world ‘invites no questions and gives no grounds for furnishing any answers.’ This is the crux of the issue. Pupils may be well rehearsed in the skills of describing the world visually – particularly through the hegemonic discipline of representational drawing and painting in the classroom, that is, in the manipulation of culturally specific visual codes and conventions, but they also need to learn how to ask questions of art works. Without the questions there is no possibility of any answers. Without an awareness of art as a source of ideas and meaning, often in and of itself, then it is difficult to extend pupils’ own art practice beyond the painstaking representation of cheese-plants, crushed cans and trainers and the appropriation and application of images and surfaces from visual examples.5

If interpreting art is integral to making art, then the question of how to teach interpretation needs to be addressed. We suggest that the skills of interpretation can be taught effectively by introducing and instilling a disposition for looking at visual art. Such a disposition has thinking, rather than making, at its centre. Approaching the process of interpretation with a toolkit of thinking skills is particularly useful with regard to contemporary visual art, in which meanings can be contradictory, multiple and are certainly open-ended and unstable. In the light of such open-endedness, teaching the skills of interpretation benefits from a structured approach and method. Even if the art work is interpreted as meaning both A and Not-A, or A, B and C, so long as the process of arriving at these interpretations is rigorous, pupils can have confidence in them. The notion that works of contemporary visual art can have multiple interpretations which are created by the viewer is the alternative to the traditional approach to understanding an art work which emphasises the transmission of meaning from teacher to pupil. In this alternative model, the pupil participates in culture through dialogue and the construction of meaning from a range of propositions which between them inform a process of critical engagement. The NFER research would suggest that while the theoretical context of postmodernism, in which the world is given meaning through local, personal narratives rather than one grand, master narrative, is by no means new or controversial, the extent to which it informs the thinking behind teaching art and design in the classroom is debatable.

The Summer Institute at Tate Modern aims to provide teachers with an opportunity to develop confidence in working with modern and contemporary art as a teaching and learning resource. This is achieved through sharing and developing strategies and skills for interpreting modern and contemporary art. The week long course enables teachers to join a community of enquiry, reflecting and debating the histories, theories and practices which inform modern and contemporary art. Accredited routes for progression are offered through Tate Modern’s partnership with Goldsmiths School of Education MA in Culture, Language and Identity, for which we have developed a one term module on contemporary art and pedagogy.

In 2002 a group of fourteen teachers took part in the Summer Institute, six of whom taught at primary and junior level and eight at secondary/sixth form colleges. They included an NQT (Newly Qualified Teacher), two Art Co-ordinators at primary level and three Heads of Department at secondary level, with the majority of the cohort at mid-career stage and working in mainstream education. One teacher was working in a school for children with Special Educational Needs, and one was approaching the end of her teaching career, with over thirty years of experience.

The dominant aims (those which were shared by three or more teachers) of participating in the course were stated as:

- Developing confidence through building up knowledge and understanding of concepts and ideas in contemporary art

- Finding new ways of engaging pupils with modern and contemporary art

- Being part of a network of teachers, and learning from the group interactions

- Invigorating a personal relationship with modern and contemporary art

- Putting contemporary art in context

Additional aims included:

- Exploring possibilities for cross-curricular work at primary level

- Enabling pupils to question more their work and the work of others

These aims were met through a loose but nevertheless methodological approach to looking at art. This method did not place a stranglehold on what is an essentially creative act of making meaning. Rather, it offered a way of scaffolding what can otherwise seem an amorphous process with no clear way in. The Ways of Looking method adopted from Tate Liverpool and used in Tate Modern’s Schools Programme provides a basis for creating interpretations of art works through four distinct frameworks: A Personal Response, Looking at the Subject, Looking at the Object and Looking at the Context.6 Each framework sets out a series of questions that give depth and breadth to the act of looking. The plural structures of interpretation offered by the four frameworks create plural outcomes, manifest as multiple interpretations of art works. Using the frameworks with teachers in the action-research project from the Summer Institute enabled us to identify some of the difficulties encountered in the process of interpreting contemporary visual art, and suggest some activity-based strategies for overcoming them, which could be adapted and adopted for use with pupils.

We selected action-research as our mode of enquiry because its principles of collaboration and learning through doing are central to our approach to teaching and learning in the gallery. Action-research turns all the people involved in a project into researchers, based on the belief that people learn best, and are more willing and able to apply research findings, through doing the research themselves.7 This mode of enquiry also enabled the initiating researchers to occupy different roles within the group appropriate to the work we were engaged in. These ranged from ‘planner leader’ (planning for the week’s course and introducing each day’s activities), to ‘catalyzer facilitator’ (initiating activities using the Ways of Looking frameworks in the galleries) to ‘listener observer’ (during lively debates opened up by the frameworks) to ‘synthesizer reporter’ (drawing together key ideas and revisiting experiences through a plenary discussion).8 A further key aspect of action research, which made it the most appropriate research method for this project, is that as initiating researchers we were not required to remain objective (or attempt to do so). On the contrary, we needed openly to acknowledge our bias to other participants, a process supported by the first Ways of Looking framework, A Personal Approach.

Throughout the week teacher-researchers were asked to keep a Looking Log. In using the term Looking Log we deliberately moved away from the notion of a ‘sketchbook’ which is redolent of a dominant approach to enquiry through formal examination of the art work, towards the notion of a research journal which would support the holistic approach of action-research in allowing for several different methods rather than a single method of collecting and analysing data. In the Summer Institute these methods included an entry and exit questionnaire asking teacher-researchers about their expectations for the project and giving an indication of the distance travelled by them throughout the week; a seminar situation at the start of each day in which key texts (set as homework from the night before) were discussed; talks and presentations by visiting speakers, and the gallery sessions themselves in which the Ways of Looking frameworks were extended and enriched by a range of activities. The combination of these methods meant that by the end of the week the Looking Logs offered a rich source of data about approaches to interpretation, data in which there is a coherence between text and image as part of the same process of enquiry and problem-solving. The case studies referred to below for each of the Ways of Looking are based on and where appropriate supported by evidence from these Looking Logs.

The biggest stumbling block in reading artworks was having confidence in the concept of multiple interpretations. At the beginning of the week the group exhibited an enthusiasm to identify a single authoritative voice to deliver what was considered the definitive meaning of a work. Most often this ‘true’ voice was taken to be the artist’s intention. If this strategy failed, another authoritative voice was substituted, most commonly that of the art historian. For example, a reading early on (before the process of learning new habits of looking had begun) of Interior with a Picture, 1985-6, by Patrick Caulfield, concentrated on a commentary about one aspect of the painting by an art historian. By focusing narrowly on the picture within a picture (the carefully copied still life Meal by Candlelight by seventeenth-century German artist Gottfried von Wedig), the desire to extrapolate this one authoritative voice in order to create meaning for the work prevented any consideration of the rest of the painting and a reading of the still life as one element of an overall schema. This resulted in a overly focused reading that did not consider how this one component of the painting functioned in relation to the rest of the work.

The desire of the group for an authoritative voice to deliver the meaning of an art work is not unique. One of the texts discussed by the group was a chapter from The Methodologies of Art by Laurie Schneider Adams. In it, the writer refers to a commentary in Jacques Derrida’s The Truth in Painting on two responses to Van Gogh’s painting Shoes, 1886 (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam).9

The interpretations are those of the philosopher Martin Heidegger and the art historian Meyer Shapiro. Heidegger uses the painting as a starting point for an elaborate evocation of the peasant woman who wears these shoes, locating her within a particular landscape and imagining her ‘uncomplaining’ in the face of difficulties. This kind of poetic and imaginative reading can be compelling and, in the gallery, is justified as a purely personal response (‘this is what it means to me’), but not as an interpretation. Derrida notes that Heidegger is actually using the painting to support a particular ideology. In turn, Shapiro uncovers Heidegger’s ‘error’ by stating that the shoes actually belonged to the artist and were city shoes not country shoes. His reading is that the shoes are a ‘sacred relic’ with biographical significance. In practice he substitutes one ‘truth’ for another: as Schneider states, it becomes a struggle over who ‘control[s] the truth of the shoes’.

The group discussed how this game of substituting one authority for another is equally problematic in the gallery as it treats the art work as if it were a problem that had a single solution. Derrida challenges both interpretations: what if the shoes are not even a pair? At first this seems like an absurd line of questioning but it is in fact rooted in a close observation of the painting. The more we look, the more doubt enters into our mind. When this most common-sense assumption is challenged, Heidegger and Shapiro’s claims for the ‘truth’ of the painting become untenable. Derrida uses various strategies in his onslaught on our most basic assumptions. This was not a comfortable experience for the group, who found his constantly shifting frames of reference and wordplay intensely destabilising. Moments of coherence occurred in the text but there was always the possibility that the frame of reference would shift again and our certainties would once more be undermined.

The most useful aspect of this commentary for the action–research project was that it revealed the underlying dangers in two common responses to looking at art and making what seems like a reasonable interpretation: getting carried away by a personal response or filling in the gaps and substituting one authority for another. The personal response is a vital part of any reading of a work of art, but it must be tempered by the discipline of looking with both depth and breadth and the courage to challenge even our most basic assumption about a work. It also introduced the notion of instability into the experience of interpretation, which was a recurring feature of the project. Many of the initial interpretations given by teacher researchers at the start of the Summer Institute shared this need for recourse to a ‘comfort blanket’ of authority or expertise, which seemed to demonstrate a lack of confidence in developing open-ended interpretations based on participants’ own experience of looking at the work.

One might argue that the issue of authority is particularly pertinent to art teachers. There is an expectation that they should occupy the position of subject expert within the classroom (even if, as has been argued in debates around the perceived ‘deprofessionalisation’ of teaching, this position has been eroded somewhat since the formalization of curriculum in 1988 and subsequent Orders). Art and design pupils have a potentially limitless number of artists and art works, and an extremely wide range of media and techniques with which they can work, there being no ‘set texts’ in terms of artist, time period or media for critical analysis. But teachers do not need to be an authority on all potential meanings of art works they and their pupils encounter. Rather, they need the skills to support their pupils in critically engaging with these art works, enabling them to unlock ideas which may then feed into their own art practice.

Each day of the summer school took one of the four Ways of Looking frameworks and tested and expanded it through a mix of gallery-based activities and discussion of excerpts from set texts.10 Visiting artist Emma Kay, art historian and curator Kathy Battista and Jane Burton, Curator of Interpretation at Tate Modern, offered additional perspectives on the process of interpretation through discussions of their professional practices. While the four Ways of Looking frameworks inflected with and informed each other throughout the week as a dialectic process, participants continually had recourse to their personal response, the framework taken as the starting point for looking at a work of contemporary visual art.

Taking the personal approach as the first framework for looking is a principle located within constructivist learning theory which posits that the construction of meaning depends on the prior knowledge, values and beliefs of the viewer, who finds points of connection and reference between these aspects of themselves and the art work.11 It is essential to differentiate between an initial response to and an interpretation of an art work. They are not the same thing. Responses are informed by the ‘connotational baggage’ brought by a viewer to an art work.12 This baggage is personal and multifarious. It is about the connections a viewer brings to their reading from their experience of the world. While on the one hand personal responses can provide fertile ground for exploration, if treated unreflexively they can stymie interpretation as the art work is submerged beneath the poetry of personal association, reaching a discursive dead end. An interpretation of an art work is constituted through a process of looking which takes into account a range of perspectives for thinking about the work beyond the personal.

Thus, the process of developing interpretations was achieved through expanding on personal responses and building up new habits of looking at art through a programme of activity centred teaching in the gallery. All of the activities were designed to foster a community of enquiry, in which discussion and debate were integral and each person’s ideas were equally significant. The following examples take each of the frameworks for looking and demonstrate how an activity for each was used to give looking, and consequently the process of interpretation, more depth and breadth.

Fig.2

A response by Alison Mawle to Pacific 2000, by Yukinori Yanagi (Tate)

A personal approach

This activity invited teacher researchers to reflect on and extend their immediate responses to a work. After a short period of looking (one minute) at Anslem Kiefier Let a Thousand Flowers Bloom, 2000, the group wrote down their initial responses to the work in a stream of consciousness format: ‘Loss of innocence, hope, once vibrant, now withered, consumed by brutality. The battle for power – nature or mankind? A flickering flame.’13

After sharing and discussing some of these poetic responses by way of an ice-breaker activity, the group paired up and each pair chose another work in the Landscape /Matter/ Environment display. One person was allotted the role of interviewer, the other interviewee. The interviewer’s task was to support the interviewee in extending their personal responses to the work through questioning the cause and effect of specific responses, and to provide a more objective view of the interviewee’s pathways of enquiry which were mapped diagrammatically into the Looking Logs. This reflexive critique of an initial personal response aimed to uncover some of the biases and assumptions upon which readings of art works were made. Creating interpretations requires a measure of self-awareness in that the viewer’s personal history, gender, social class, race and ethnicity will inform a reading of an art work. Diagrammatically mapping the process of enquiry demonstrates how fertile a personal response to an art work can be when treated reflexively. On reflection, the links and associations offered by personal responses can offer new vistas for exploring the art work and be as revealing about the viewer as about the work itself.

In teacher-researcher Ali Mawle’s mapping of her personal responses to Pacific by Yuki Yagonari we can trace a movement of thought from imagination to metaphor to a very specific set of knowledge that she brings to the work which if treated unreflexively would close down an interpretation of the work. In answer to the question ‘What does the work remind you of?’ she starts by noting a visual similarity between the cracks in the flags and river tributaries. Already this response is literally located in a specific world view – an aerial one. This prompts a layering of associations – she relates the river tributaries to cracks in concrete, which in turn become metaphorical cracks in notions of republics and nationhood. Thinking about the realm of politics leads her to make a very specific response to the work which is articulated as ‘Germany – invasion spread out then stopped.’ The specificity of this halts the process of layering associations. A consideration of her emotional responses to the work records feelings of fascination about the ideas in the piece and its method of production. Thinking about the processes involved in making the work leads her to wonder what the seemingly random paths of the ants might represent – which in turn invokes thoughts of rationality and chance. In the plenary session the teacher-researcher spoke of how intrigued and surprised she was by this process of tracking her responses. Her diagram references particular world views and knowledge brought into play by the art work, for example a political language of republics, nationhood, invasion, force and power and a philosophical language of belief systems, of free will, reason and chance. It indicates the non-linear quality of responses to the art work, in which ideas are fluid and iterative.

Reflecting on the activity in a plenary session, the following key observations were recorded by the group:

- Personal responses reveal belief structures. Reflecting on a personal response enables us to consider what informs that personal response.

- The dialectical approach enabled a layering of responses in which associations and links were found to be fruitful methods of broadening responses.

The dialectical approach provided checks and balances on personal responses, enabling the interviewee to stay focused on the art work. Questions for further exploration which were noted for further consideration the following day included:

- What do we need to know to develop meanings?

- How can multiple personal responses be linked and refined?

Looking at the subject

In the fast-moving world of contemporary visual art it can sometimes seem that the only constant is change. This makes keeping up with subject knowledge something of a challenge. Or does it? Teaching pupils the skills of interpretation in such a precedent-defying discipline as contemporary visual art poses the question of the status of knowledge. The anti-traditional nature of contemporary visual art means that there is no accompanying stable or substantive body of knowledge, but rather a plethora of theoretical and critical texts which ebb and flow around and within the art. What kinds, and how much, subject knowledge is useful in the process of interpretation is therefore a key question.

Finding a way into an art work which has meaning for pupils does not necessarily tally with knowing everything there is to say about an artwork. An activity in the Nude/Action/Body display highlighted how applying a priori knowledge about an artwork, artist or movement can sometimes act as a block to active and focused looking. Teacher-researchers were invited to curate a route of between three and five works through the galleries using the Looking at the Subject framework as a way of making links between the works. The selected works could demonstrate how artists had expanded or problematized the overall theme of the display. However, it is fair to say that the resulting routes were muddled; rather than making arguments for connections based on what could be seen, links were made through referencing a priori chunks of knowledge about the artists or the art works. The routes were not a set of interpretations but instead a collective, disjunctive effort of rehearsed information which was not based on visual evidence. The collective nature of enquiry which this activity was designed to foster presupposes that each person’s ideas and knowledge are equally significant as potential resources for creating interpretations, but these ideas need to be tested against the art work itself. This makes possible the contradictions between many viewpoints and a single viewpoint, which is where dialogue starts. A priori knowledge can limit the way we look by tripping us up into making false connections and leading to a discursive dead-end rather than coming to a place of open ended-ness. Using the Ways of Looking at the Subject framework the group revisited their connections between the selected works and refined them to a handful of key ideas backed up by visual evidence.

This activity suggested that useful subject knowledge about the field of contemporary visual arts is as much to do with an attitude of questioning (paralleled in the making of contemporary visual art) and focused looking, as it is concerned with the detail of individual artists, movements and tendencies or with the art object itself (when such an object exists).

Looking at the object

In considering the artwork within the framework for enquiry which focused on its objecthood, we commenced with a brainstorm about the variety of ways contemporary art conveys meaning through its material and formal qualities. Working in the Still Life/Object/Real Life display, the group each chose one work to respond to purely in terms of its formal qualities, recording responses in their Looking Logs. There was a lot of discussion about sketchbook work as a creative act of translation – it was not about ‘copying’. Activities which make it difficult to recreate the chosen work pushed the teachers to focus on one aspect of the art work, extrapolate and develop it. This led to a focus on the decisions behind formal qualities in the work. Deliberately limiting options (only using collaged gummed paper, reducing a work to five lines, etc.) makes it clear that the activity is not only an act of recording but an interpretation – the teacher is forced to make quite dramatic choices within the constraints of the exercise. It allows them to avoid the pressure of feeling they have to demonstrate skill (once again this is about avoiding the temptation to fall back on a position of authority). In feedback the value of the individuality of the responses was emphasised – a sketchbook equivalent of the multiple readings idea.

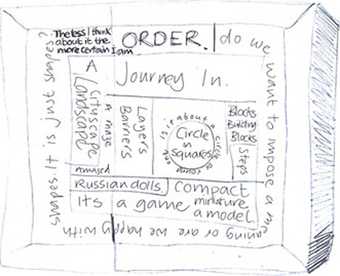

The examples from the Looking Logs suggest the importance of allowing time for a purely physical response to an art work based on its objecthood. As evidenced in the analysis of Robert Morris’s mirrored cubes sculpture called Untitled, 1965–76 (T01532), this physical response to an art work can be in itself a way of knowing a work – as one teacher researcher put it ‘the less I think the more I know’.14 But alongside a phenomenological engagement, additional ways of knowing the work start to occur, in this case through a consideration of links and associations generated through being with the work. Questions are posed and thus the discussion opens out. At the centre of this diagrammatic enquiry into the hard-edged mirror cubes is a circle: interpretation as an infinite process.

At the centre of this diagrammatic enquiry into the hard-edged mirror cubes is a circle: interpretation as an infinite process.

Fig.3

Looking at the Object

A response by Sancha Briffa to Robert Morris’s Untitled 1965–76 (Tate)

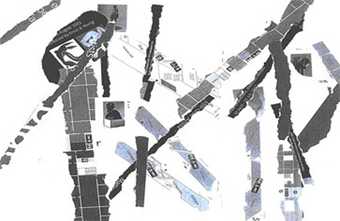

In the second example, Cornelia Parker’s Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View, 1991 (T06949) is interpreted through a collage which extrapolates the strong formal dynamics of the work and the careful placement of objects in what initially seems a random, chaotic arrangement (fig.3). In choosing to use a gallery map as her material, the teacher-researcher also makes a witty connection between the way the art work explodes and reassembles the world in a metaphorical microcosm and the way that the process of creating plural interpretations can also involve an explosion of ‘safe’, that is, finite ways of knowing the world. Just as the gallery map has been ripped up and remade in an exploratory fashion, so too in making interpretations nothing is certain except the precariousness of meaning.

Fig.4

Looking at the Object

A response by Connie Flyn to Cold Dark Matter, An Exploded View by Cornelia Parker (Tate)

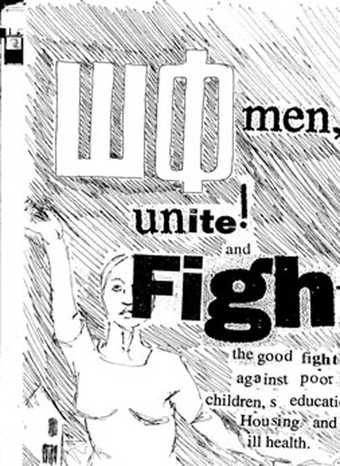

Having first noted what could be seen, these responses were then extended by discussion of the associations arising from the material properties of the object. The group moved to the Soviet Graphics room in the History/Memory/Society display in order to explore the relationship between formal characteristics of a chosen art work and its meaning. Despite the inaccessibility of the Russian poster text, meaning could still be construed through reading the formal qualities of the works – design decisions about point of view, font size and choice of graphics, the formal relationship between word and image. Despite the culturally contingent nature of even the most basic elements of the poster’s design, this activity demonstrated how interpretation took place because the group recognised the cultural framework within which the posters were designed.

Responding to the works in collage, the group used newspaper print to create new interpretations of a poster of their choice. Through doing so they connected the ‘what’ of the work – what do I see in front of me? with the ‘how’ of the work – how has the artist used their materials and the formal language of image making to convey meaning? Learning took place through the experience of re-making the art work, a visual process of interpretation.

Fig.5

Looking at the Object

A response (no name given) to a poster in the Soviet Graphics display at Tate Modern

This activity was followed immediately by a return to contemporary art works such as Rebecca Horn’s Concert for Anarchy, 1990 (T07517), in which the artist had a very different intention, that is, cultivating an ambiguity of response. This led to a discussion of the difference between ‘art’ and ‘propoganda’ and the importance and difficulty of trying to imagine the artist’s intentions. We also talked about which kind of art the group preferred – the art they felt communicated simple positions clearly or the more ambiguous approach offered by for example the Kiefer and Horn work – dealing with similar themes but with completely different intentions. The collage activity, book-ended by looking at the works by Anselm Kiefer and Rebecca Horn, worked as a way of exploring ideas about intention and the desire for (and impossibility) of a universal language.

The Looking Log examples demonstrate the investment of time and thought the group brought to developing new and personalised ways of recording information. The group was working against the ‘norm’, that is, recording the process rather than the outcomes of interrogating the artwork. We experimented with diagrammatic forms of recording responses (for example, exploring the hang in a particular room) or more linear, flow-chart approaches when we were thinking about the stages of individual looking (looking deeper, looking again). Throughout, we asked the teacher-researchers to draw on areas of their own expertise to create a personal shorthand for recording their experiences. As pupils are already very familiar with the formal language of image making, these kinds of activity can offer a good introduction to critical analysis and the process of creating interpretations.

Considering the wider context

The final framework for looking at contemporary visual art took Doris Salcedo’s Untitled, 1998 as the focus for exploring how the wider context of a work can be integral to its meaning. Untitled is an old-fashioned wardrobe which has been filled with concrete, into which a domestic wooden chair has been buried. The group engaged initially with the work through stream of consciousness writings in which its material properties were uppermost, evidenced through a parity of responses and moments of coalescence. ‘What is this? Boarded up Lion, Witch, Wardrobe – dream shut off, cold, frustrated household object. An abject object. Got hinges but it can’t open. Wood looking out of cement – stuck, lodged, uncomfortable, tight.’15

Responses to this piece were striking in their sense of mutuality. They were both generic (notions of the domestic sphere being violated or made mute, resonances of past lives and generations) and culturally located (multiple references to C.S. Lewis’s The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, a dream world that cannot be accessed, the imaginings of childhood frustrated).

When these readings were expanded through additional information about the artist and her social/political context, the discussion moved on from metaphorical associations of the materiality of the object to real-world connections between political oppression and the artist’s choice of material. For example, some of the teacher-researchers were aware of the tactic used by the Colombian mafia to weight their victims with concrete blocks in order to ensure that their drowned bodies could not be found, that they were forever ‘disappeared’. Thus, the introduction of contextual information about this piece gave the teacher-researchers the confidence to draw on and make connections with their own knowledge in a focused, relevant way.

Salcedo’s work comes out of a specific political context, and as such its placement next to the Soviet Graphics room offered another important context for discussion; the way the art work is curated in the gallery space and how this affects readings of the work. Both the Soviet Graphics and the Salcedo works were interpreted as having a particular meaning arising from a particular political context, of which the artists would want the viewer to be aware. In exploring context as a way of looking at an art work, the question arose of where to introduce contextual information. The group decided that this depends on how clearly information is communicated by the work. Even if we do not know the specific language or political context of an art work, what can we get from it purely by looking? A combination of personal responses, extended to encompass process, material and context leads to an understanding of interpretation as a combination of events, an alchemy of ingredients which creates not one single reading, but a constellation of related readings.

Future prospects for interpretation and the art and design curriculum

In looking at all the art works discussion constantly shifted between different frameworks for looking: the personal, the subject, the object and contexts for the work. A process of dialectical enquiry took place, based on deep and broad looking which afforded new insights into the work. In contrast to the beginning of the week, where the method of interpretation was to impose a single, authoritative voice on a work, and claim this as the truth of the piece, strategies for developing meanings were now multi-faceted and the group was comfortable with the concept of multiple, open-ended interpretation. Artistic intention was still considered as one of several factors that contributed to interpretation, but was not the ultimate arbiter of authority. Instead, meaning arose through a collective, discursive process of enquiry, in which personal responses were continually mediated by other frameworks for looking. Interpretation took place through an attitude of questioning in which the art work was approached from a range of perspectives which inflected with and informed each other. In doing so hypotheses about the work were tested, and some disregarded, as the iterative nature of interpretation meant that new possibilities for expanded readings were always present.

Understanding interpretation as a dialectical critique of the art work through discussion seems to be fundamental to the process of teaching interpretation skills. Art works are phenomena which are conceptualised in dialogue as well as in visual language, and as such dialogue is necessary to understand the relationships between art works and their contexts.

Within the context of the art curriculum, redressing the balance between teaching the skills of making art and teaching the skills of interpreting art is a risky business. At its heart is a destablising of traditional responses to art works and an ability to be comfortable with uncertainty. There is also the fear of exposing oneself, be it teacher or pupil, through making explicit a personal response to an art work in open discussion. The role of the teacher in this needs further attention, but it is our belief that the uniqueness of the art and design teacher in teaching a subject in which pupils enjoy a large degree of autonomy should lend itself well to teaching interpretation as a skill, with teachers developing their role as facilitators of dialogue, fostering reflective analysis and moderating discussions.

It was not the purpose of the action-research project in the Summer Institute to offer any conclusions about ways forward for integrating interpretation and contemporary visual art within the curriculum. Rather, through critical reflection on the course we hoped to demonstrate the usefulness of a structured approach in teaching the skills of interpretation with particular reference to contemporary visual art. If the art curriculum can foster an attitude of enquiry and reflection which teaches pupils the habit of giving looking depth and breadth, then the process of expanding it to encompass today’s visual art will be much enabled. But this is predicated on an acceptance in the classroom of the value of shifting contexts for interpretation in which there is no final point of stasis, and an understanding that meanings shift depending on the nature of the viewer, location, time and circumstances. Within an outcome-focused, formalist art curriculum this instability can either be viewed as a difficult concept to take on board, or as a liberating and explosive force for teaching and learning. The experience of the action research project was summarised by one teacher-researcher as allowing her to ‘break out of a trap of limited knowledge and confidence. I’ve gained a tremendous range of strategies and now value a range of responses to what I see and still want to know more’.16 Arguably, and based on the findings of the NFER/ACE/Tate research, this trap of limited knowledge and confidence informs art and design education in schools to a worrying extent. Tate aims to play a role in enabling teachers to break out of this trap through creating programmes and partnerships for teachers and trainee teachers, commissioning and contributing to educational research and strategically, and working with policy makers and educationalists to raise awareness of the importance of meaning-making as a critical component of the art and design curriculum.

Appendix

Ways of Looking frameworks (pdf 121k) from Tate Modern Teachers’ Kit 2002.