Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947) was first and foremost a watercolourist, and it was not until she was in her early forties that she took up oil painting with any consistency. Even after some years of successful painting in oil she wrote in frustration to her dealer, A. J. McNeill Reid: ‘I am in danger of forgetting I am primarily a Water Colourist – if you want me at my best & most profitable and prolific encourage me to return to them’.1 The photographer, Douglas Glass, recounts that Hodgkins had ‘two things to worry about the obligation to give them [Reid & Lefevre] enough pictures, but to be true to herself and not paint pictures just to fulfil the debt … She used to get very savage with her paintings & destroy them … oils were a great struggle. But to herself, they were far more important than the watercolours’.2

It was in 1907 that Hodgkins wrote of a frustration with her work and wondered what she could take up instead to rest her ‘weary painting nerves. A change of medium might do it’.3 Her desire to paint in oils is mentioned a year later in a letter;4 and in another she writes that she would ‘dearly love to get some oil lessons under a first rate man’.5 This she eventually did at the Parisian studio of Pierre Marcel-Beronneau (1869–1937) in 1908, ‘where I work 3 [hours] in the morning from the nude in oils. I find it most puzzling & difficult to submit to having my work swept ruthlessly away in the same way that I treat my pupils! It is quite beautiful to see him work, his strength & certainty & the delicate way his big rough hands handle the brushes & re-make a wobbly knock-kneed daub into a living breathing piece of human flesh’.6

Why Hodgkins chose Beronneau as a teacher is unknown. His painting was quite unlike her own work, exploring as it does mystical themes related to those of his teacher, the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau. Perhaps a smaller studio may have been more appealing for someone who had taught art for twelve years already.7 Giving up the attempt to paint in oils due to her success in watercolours, Hodgkins did not take up oil painting seriously again until World War One when she settled in the artists’ colony at St Ives, Cornwall.8 One of her earliest examples is Loveday and Ann: Two Women with a Basket of Flowers, 1915, (Tate N05456). Her unusual approach to oil painting – and later to gouache– appears to be influenced by her long attachment to the watercolour technique. Her method of painting with quick but numerous adjustments are also seen, with interesting and sometimes problematic results.

Frances Hodgkins

Wings over Water (1930)

Tate

Hodgkins was 62 when she painted the oil Wings over Water, 1931–2 (fig.1) but, despite her age, her work was considered innovative and received significant critical acclaim. This provided only limited financial security but it allowed her finally to give up teaching and to work as an artist full-time. There is very little information about her technique or sources of materials in her letters. However, her constant concern about financial matters is clear and this would have influenced her choice of materials, as an examination of her paintings reveals.

Wings over Water depicts the view from the artist’s rooms in Bodinnick, Cornwall, during the winter of 1931–2. Curtains enclose the scene on either side. The table in the foreground has objects arranged as a still life and in the distance is an evening landscape of hills, water and sky. The landlady’s parrot sits on the fence in the middle view, silhouetted by the River Fowey behind. Although it is closely based on an elaborate drawing of the same name, the artist has struggled to resolve the image in the oil. The modifications became apparent during the technical examination which made it possible to make some sense of the numerous layers of paint and the areas of impasto, which in turn has assisted in the dating of the painting.

The painting

Fig.2

Frances Hodgkins

Wings over Water c.1931–2

Reverse in raking light before lining

Note the In Cornwall inscription, upper left

Tate. Presented by Geoffrey, Peter and Richard Gorer in memory of Rée Alice Gorer 1954 © Tate, London 2006

Wings over Water measures 710–713 mm high x 915 mm wide, a format that is more square than the average prepared canvas.9 The linen canvas is a plain open weave, coated generously with animal glue, followed by a single ground. Open-weave canvases were not as popular in Britain as in mainland Europe, although the importation of rolls of prepared canvas from Belgian suppliers such as Claessens was common at the time. Stretching was more likely to have occurred in Britain, to local standard sizes in inches. The canvas is attached to a stretcher without crossbars, which is rather inadequate for the size, particularly when one considers the weight of the many paint layers applied by Hodgkins (fig.2). The same type of commercial preparation was found on other paintings by the artist including Pastorale, c.1929–30, and Still Life with Landscape, c.1930.10 A single priming and loose-weave canvas would have been a much more economical option compared to a tighter weave with double priming, both requiring more materials and labour.

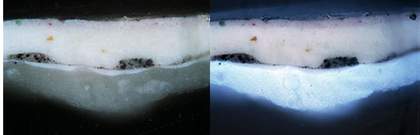

Fig.3

Cross-section showing single ground (lower semi-transparent layer with thin ‘flatting’ coat on top) plus grey and off white paint layers. Incident light (left) and ultraviolet light (right). Photographed at 250x

The single ground consists of a thin opaque ‘flatting’ coat above a semi-transparent layer below (fig.3).11 Ground preparations of a similar appearance have been observed in paintings by the Camden Town group, which was first established by Walter Sickert, an artist with whom Hodgkins was very familiar.12 In Wings over Water, the lower ground of chalk and zinc white fluoresces brightly indicating the presence of animal glue size, whereas the binder in the thin white lead layer above is linseed oil.13 As oil from the flatting coat has soaked into the lower layer, the ground continued to take up oil from subsequent paint applications. Absorbent grounds caused the paint to set very quickly and become matt and dull (artists such as Gwen John used this effect to produce oil paintings that reproduce the clarity of watercolour).14 However, the ability of an absorbent ground to take the oil is lost if too many paint layers are applied. This is certainly the case with Wings over Water and so the choice of ground seems at odds with the technique. The paint has been applied thickly and in numerous layers. Scumbling is frequently used to modify the opaque colours below and much of the work is done wet on wet.15 The surface brushwork is clearly apparent, as is an underlying, unrelated impasto indicating changes in composition. In some areas, the artist has used sgraffito (scraping through the paint with a palette knife or brush-end) to reveal underlying drier paints and to create texture or emphasis (fig.4).

Fig.4

Raking light of Wings over Water reveals an animated surface texture from sgraffito, impasto and palette knife

The paint medium is linseed oil,16 the consistency of which appears to have been modified by the addition of chalk and other dry pigments. Under high magnification, the pigment particles can be seen to be much larger than one would expect from commercially prepared paint which would have been thoroughly ground during manufacture. Compared with a sample taken from a painting by Julian Trevelyan of a similar period (Basewall, 1933, Tate), the particles from Wings over Water are about four times the size (fig.5).

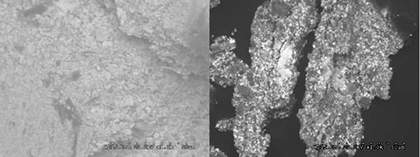

Fig.5

The pigment particle size is much larger in a sample taken from Wings over Water (left) than from Julian Travelyan’s Basewall, 1933 (right)

It is likely that the artist added chalk to provide a particular texture. In her experiments the materials historian Leslie Carlyle has added chalk in a variety of proportions to lead white and has found that although chalk changes the brushing quality of the paint, it holds its shape very well. However, it is likely that the two components would have to be ground together to achieve a smooth consistency.17 For an artist who was looking for a dense material that can be scraped back, this may have been ideal. Large chalk particles have also been found in the paintwork of Gwen John, and so it is possible that the modification of paint in this way was not an isolated practice.18 The stiffened paint in many layers in conjunction with an absorbent ground by Hodgkins will have contributed to the cracking that has occurred in Wings over Water. This also appears to have been a factor in the deterioration of other oil paintings by the artist at this time.19

Hodgkins has altered tube colours by adding dry pigment. Visible on the surface as black flecks, dry pigment is suspended in the pale green paint of the cloth in Wings over Water. It can also be identified in the cross-sections because it is not so finely ground. Large black particles of dry pigment are contained in the blue and brick red paint; red organic pigments in the pink, purple, and grey; green and brown in the beige; and Vandyke brown particles added to a bright mixed orange. Large black and brown particles of dry pigment are found in several other paintings from the 1930s and this appears to have been a useful way for Hodgkins to modify shades.20

Lead white is mixed into almost all of the colours, making them paler and more opaque. This approach is at odds with nineteenth-century oil practice where the transparency of the medium is utilised to create depth and underlying layers are modified by surface glazes. Opacity produces a solid mass, suitable for the process of simplification and surface emphasis preferred by the modernists. Variation is achieved by brush technique – scumbling and scraping, and texture takes greater priority.

When describing Hodgkins’s colours in a retrospective exhibition at the Lefevre Galleries in 1946, critic Eric Newton wrote: ‘She can … make certain colours “sing” as they have never done before – in particular a certain milky purplish-pink, a most unpromising colour: she can make greys and browns look positively rapturous: She can juggle with colour orchestrally’.21 The colours Hodgkins used were greatly admired, and a similar purplish-pink is found in the Auckland Art Gallery painting Berries and Laurel, c.1930, comprising a variety of colours made milky by the addition of lead white (a bright organic red, carbon black, viridian and a lemon organic yellow). Similarly, in Wings over Water, very few colours are unmixed, the most complex being the greys which include such pigments as Vandyke brown, bone black, vermilion and an organic blue.

Hodgkins used plenty of black for mixing and in 1917 had recommended it to her friend and former student Hannah Ritchie for watercolour painting:

Do you use black? I find that using pure paint & and only mixing them with black when you want deeper tones keeps purity & unity throughout. viz:

blue with black

r. madder ”

Vermillion   ”

Viridian ”Drop cobalt and vermillion – I think it such a sickly mixture & becomes a habit and monotonous. Transparent Viridian, lemon yell: & aurelion [aureolin] are my colours for greens. Viridian is indispensable & absolutely pure. You will find viridian & rose madder make exquisite greys for skies etc.22

This advice also seems to hold true for her work in oil many years later and, in Wings over Water, black is a common addition. Black pigment has been mixed into the blue of the sea, the pale green of the cloth, a brick red orange near the lower edge at right, and the purple near the lower edge at left. Black is also used to create shadows, both as an outline and as the colour of the tabletop. In addition, viridian is indeed absolutely indispensable to Hodgkins, and is found in many of her oil paintings. In Wings over Water, it is mixed with lead white but also used independently, in the vivid green of the mimosa leaves.

All of the pigments identified in the painting had been available since the nineteenth century or earlier, except for the organic colours, of which there are a surprising number. The twentieth century saw a massive increase in the development of these pigments and although they were readily available in the 1930s, they were not as popular as they are today because of uncertainty about their permanency. They tend to be transparent and are very strong colorants and this may also explain the frequent use of white. Many of the paints have large quantities of extenders – chalk as already mentioned and thought to be supplemented by the artist, and also gypsum, barytes and in some cases pumice and mica. Although the quantities are not great enough to imply that the paint was intended for home decorating rather than art purposes, these extenders may indicate a cheaper grade of artist’s paint.

The painting appears to have been significantly reworked by the artist while it was in its frame, and the overpaint only extends to what would have been the frame edge. The signature is found in this repainted area, a characteristic ‘Frances Hodgkins’ in the lower right corner, carried out in sgrafitto on black. There are a number of pinholes in the edges outside the repainted boundary and these are regular enough to have been used to separate the painting from packing materials while it was still wet and before framing. This seems to have been a common practice for the artist in her rush to get things out, and is found in other works such as Berries and Laurel, c.1930 and Self Portrait: Still Life, c.1935 (both Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki).

No dirt was found between the layers of paint in the overpainted area, which probably indicates that not much time had elapsed between the original painting and reworking. However, the lower paint was dry enough not to be damaged from the frame around the edge, and scrapings tend to stop at this layer and not the ground, indicating that the paint could have been several weeks old. Many of the changes to the painting are visible as lumps and indentations in the surface, particularly on the left. Such irregularities have been shown by x-radiography to reveal more flowers below the vases and a bowl to the left of the parrot, modifications to the table, and it is likely that the width of the curtains has been altered. Below the left shell was a stem of roses on the cloth which is reminiscent of the downward pointing roses in Self Portrait: Still Life (fig.6). This may indicate that the earlier painting might have had more in common with the decorative preliminary drawing with its patterned surfaces.

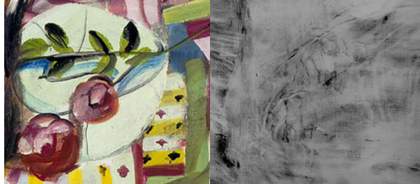

Fig.6

Similar downward pointing roses in Self Portrait: Still Life (left), and Wings over Water x-radiograph (right)

Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki; Tate

Despite the oil being very similar to the drawing (fig.7), there have been numerous changes during the painting process, indicating difficulties in reaching an acceptable conclusion. The artist is known to have carried out many sketches before painting in oil. Her friend Geoffrey Gorer stated that ‘She didn’t [paint] quickly and spontaneously at all. She took tons and tons of notes, small sketches, usually in front of the object … and then destroyed those and then slowly worked to make a composition in the studio’23 Clearly she did not destroy them all, but her friend Elsie Barling also says of her painting process that, ‘She altered quite a bit as she did it. She wasn’t just spontaneous … she used to have several ‘try-outs’.24

Fig.7

Frances Hodgkins

Wings over Water 1931–2

Pencil

Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Whatever the process involved, Hodgkins appears to have been very satisfied with the end result and included it in her selection to go in the 1940 Venice Biennale. To Rée Gorer, the owner of the painting and mother of Geoffrey, Hodgkins wrote:

He [McNeill Reid] is very fussed over the Venice affair & what best to do and how not to spend more than necessary on frames etc He told me that your picture was being re-varnished wh [sic] will do it a lot of good – It is good of you to spare it for so long I think that it will be the peach of the Show & with out any doubt win the prize for foreigners of 2,500 lire.25

It is likely that this is when the painting was varnished for the first time, while it was in its frame.26

As already mentioned, the thick paint layer of Wings over Water was too stiff and heavy for the loose-weave canvas and as a consequence numerous cracks and deformations have developed. This is a common problem with oil paintings by Hodgkins, and explains why so many of her works have been lined.

Dates and titles

Frances Hodgkins had gone to Cornwall in November 1931, intending to stay for Christmas with her old friend, Gertrude Hall (née Crompton) and husband. Finding their house in Fowey too remote and windswept, Hodgkins moved to the small village of Bodinnick-by-Fowey across the water. Separated by the tidal river Fowey, Bodinnick is primarily a ferry landing with pub and a scattering of dwellings that follow the road. It is nestled into the hill and looks down the river to the sea, framed by the beautiful villages of Polruan to the east and Fowey to the west (fig.8). She wrote of her discovery: ‘So I searched round and found Bodinnick up a creek, over several ferries & quite unforgettable after dark – and here I am’.27 Hodgkins’s temporary home was ‘The Nook’, which she described as ‘neither of the ‘Rookery’ or the ‘Cosy’ sort but suits my needs – no other fool could stand it’.28 In December a majority of her paintings were of views through the window. She complained: ‘It is too cold to work out of doors – Besides which the colour is so dark & sodden with damp – Bracken is bright red – black ships on the river’.29

Fig.8

Photograph taken from Bodinnick, Cornwall, April 2004

© Sarah Hillary

Arthur Howell, Hodgkins’s dealer, had been forced to close his gallery in early 1931. Although this was intended to be a temporary measure, the economic depression worsened and the situation became irreversible. Howell therefore approached an old-established gallery, Reid and Lefevre, on Hodgkins’s behalf to see if they would take over her contract. But in a letter sent to her in Cornwall in late 1931, Howell told Hodgkins: ‘they were not pleased with the pictures I sent them … They are getting a little tired of the same kind of still-life’.30 Eventually the matter was resolved after a meeting in London on 6 February when Hodgkins showed Duncan Macdonald, director of Reid and Lefevre, the work that she had recently done in Cornwall. A new contract was drawn up which was more generous than her previous arrangement with Howell, but again required an unrealistic number of works to be produced. ‘They would cover the cost of framing and pay 10 pounds for oil paintings and 5 pounds for watercolours until the sum of 200 pounds had been reached.’31 The payments would be quarterly and Reid and Lefevre could reject works they disliked. The contract arrived on 11 February 1932.32

In February Hodgkins also exhibited six paintings at the eleventh exhibition of the Seven and Five Society, held at the Leicester Galleries.33 These comprised Herrings (no.7); In Cornwall (no.21); Arum Lilies (no.35); Red Jug (no.39); Whiting (no.43); and Pottery (no.46). In Cornwall is the original title for Wings over Water. It is hand-written on the reverse of the upper stretcher bar and also on the British Council label for the ‘Biennale Venice’.34 Other paintings in the exhibition included a work by Winifred Nicholson, Fishbourne, Isle of Wight,1929–31, in which a view from a window is framed by curtains and the objects on the window sill, showing clear similarities to the painting of Hodgkins at the time. However, Hodgkins developed the genre of still-life landscape further than her contemporaries by taking the still-life objects into the landscape. This resulted in strange juxtapositions of landscape and still life interacting in an irrational manner, akin to surrealist practice.35

Hodgkins had been elected as a member of the Seven and Five Society in February 1929 after being nominated by her friend and fellow artist, Cedric Morris. It was considered to be ‘one of the most forward-looking of the London exhibiting societies’ at the time and its focus on lyrical naturalism would later be replaced by one on modernist abstraction.36 In her work Hodgkins attempted to depict ‘the character and essential spirit of the place in the simplest manner’.37 This meant that her work had a natural affinity with the faux naïveté of the group in the 1920s.38

Hodgkins, as mentioned above, had been in Bodinnick for about a month, from early December 1931 until around 7 January 1932. The work was exhibited in February 1932 and it is assumed that the reworking and framing occurred some time within this period. The pinholes may indicate that she painted the work in Cornwall but modified it in London when it was framed. That would certainly allow enough time for the first layer to dry. An alternative explanation is that she worked from the elaborate drawing and completed the painting in London before the exhibition.39 However, this seems less likely, due to the thickness of the paint and the relatively short timeframe for drying.

Hodgkins was back at ‘The Nook’ by early March and by then the weather had improved and she could paint outside. ‘There have been some perfect days when I have spent 6 hours outside in the woods – sheer enjoyment.’40 She was kept company by the landlady and her family, and saw the artist Winifred Nicholson and her children, who were staying at Par, near Fowey.41 In April she wrote to her friend Dorothy Selby apologising for the delay in her correspondence, but hoping that she would come down and stay. Her frustration about recent events and subsequent bad language is blamed on the landlady’s parrot: ‘I have been waiting, like yourself, for others to make up their b–y minds if you’ll forgive me the word – which I catch from the parrot whose language is shocking.’42

Fig.9

Frances Hodgkins

Wings over Water

Oil

© Leeds Museum and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

The parrot also features in another painting titled Wings over Water, which was donated to the Leeds City Art Gallery by the Contemporary Art Society in 1940 (fig.9).43 The view is further to the left and includes ‘Ferryside’, the large white house that dominated her view to the sea, which was owned by the actor-manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and where he and his daughter the writer, Daphne, lived. The still life has been moved further into the landscape; gone are the curtains and clear evidence of the interior. One has the sense that the weather has improved since the earlier painting. A green and red parrot swings on a branch above, silhouetted by the glassy green of the river Fowey directly behind. A rather bare intermediate landscape provides the illusion of distance between the foreground and the white du Maurier house propped on the edge of the water, with ferries docked to one side.

Fig.10

Frances Hodgkins

Green Jug Jade Sea

Oil

Private collection, New Zealand

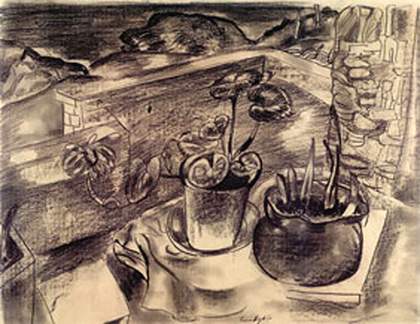

Fig.11

Frances Hodgkins

Still Life and Landscape, Bodinnick, Cornwall

Pencil and charcoal

Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

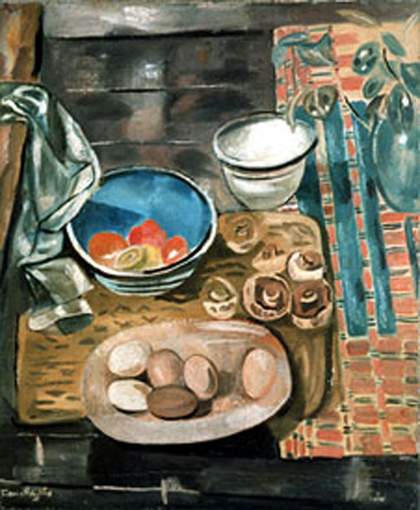

Common motifs appear in a number of works, which may link them to the Bodinnick sojourn. They include Green Jug Jade Sea (fig.10), Stil Life and Landscape, Bodinnick, Cornwall (fig.11), and Still Life with Eggs and Mushrooms (fig.12). A cherry jug and dark slated table in the Leeds Wings over Water are also found in the oil, Green Jug Jade Sea.44 In addition, there is a similar handling of paint, use of bright colour and simplification of forms. The foreground takes greater priority in Green Jug Jade Sea and this is taken a step further in the related painting Still Life with Eggs and Mushrooms (Brighton and Hove City Museums), where the distant view has been omitted altogether. Both paintings include the same dark table with horizontal planks, a green jug of leaves and bowl of eggs. Still Life and Landscape, Bodinnick, Cornwall, in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, is a drawing that relates closely to Green Jug Jade Sea. It overlooks the same courtyard with low brick wall and on the table in the foreground is the potted cyclamen found in both images. On a recent visit to Bodinnick, it was possible to see that a low wall is present at the end of the courtyard used by Hodgkins, but a conclusive comparison was hampered by difficulties of access and a thick layer of ivy.45

Fig.12

Frances Hodgkins

Still Life with Eggs and Mushrooms

Oil

Collection of Brighton and Hove City Museums

The room at ‘The Nook’ was only available until 14 May 1932 and Hodgkins was back in London by 29 May when she wrote to Dorothy Selby:

My Dear Dorothy / Just back from Cornwall – after all I stayed out the week – weather too good to leave – allowing me to get some 2 or 3 really nice things, also to finish my first batch in comfort. They are on the wall now – 11 of them – & I must confess look rather jollier than I imagined. The Hagedorns came for a P.V. after I had lunched with them today – and they were very complimentary – think them far away best work I have produced – let us hope my dealers may agree.46

According to a letter written by Geoffrey Gorer in 1955, Wings over Water was painted in London and was bought directly from Hodgkins’s Hampstead studio by Rée Gorer.47 Eric McCormick also writes that at the end of 1932 Hodgkins found a studio in Hampstead (‘a small artists’ colony’):

Calling at the studio one day with her son, Mrs Gorer saw an oil painting based on a drawing done at Cornwall. She was immediately attracted by the work and insisted on buying it. The proceeds of this windfall helped Frances to leave England and winter at Ibiza in the Balearic Islands.48

The painting Mrs Gorer bought was certainly the Tate version and it is likely that Hodgkins continued to work on it after the Seven and Five exhibition until its time of sale. It continued to be called In Cornwall when it was included in the British contribution to the 22nd Venice Biennale in 1940 and was described as lent by ‘Mrs Gorer’.49 By the time that Arthur Howell’s Frances Hodgkins: Four Vital Years was published in 1951, it was described as Wings over Water, owned by Mrs R A. Gorer, an oil painted in 1930, measuring 28 x 36 in. and signed. The Leeds painting of the same name is wider and shorter at 27 x 38 in.

Both paintings were favourites of the artist and Hodgkins had hoped to include them in the Venice Biennale, but for some reason only In Cornwall was exhibited. In a letter to Peter Watson of Horizon magazine in 1941, Hodgkins wrote: ‘Another painting I am rather partial to is Wings over Water shown at the National Gallery & now at Leeds Art Gallery’.50 When In Cornwall, (now Wings over Water) was donated to the Tate Gallery in 1954 by the Gorer family, Geoffrey Gorer wrote that:

The version we got was one of the very few pictures with which she expressed herself completely satisfied shortly after painting it – she was usually full of criticism of the failure of her work to achieve what she wanted – and was delighted when my Mother said enthusiastically ‘I have got to have that’.51

Conclusion

It is most likely that Hodgkins began the painting of Wings over Water in Bodinnick in 1931 and completed it in London in 1932. Her determination to reach an acceptable conclusion resulted in significant repainting being carried out and the resultant thick paint layer, with textured surface, became a characteristic feature of the artist’s work. Financial constraints had an effect on the choice of materials, but Hodgkins manipulated the qualities of the paints to produce interesting and individual effects. The famous colours, so remarked upon by Eric Newton and others, appear to be the result of a great deal of mixing, with some of the combinations quite ‘queer and surprising’ in themselves.52

The change in title from In Cornwall could have been due to confusion over time, or perhaps reflected an active poetic preference by the owners of the painting. Whereas in the years following World War One, the title Wings over Water would have brought back memories of warplanes over the Channel, in the early 1930s Hodgkins depicts a more playful moment. The focus of the painting is a parrot looking straight back at the artist, silhouetted by the water behind. The bird is apparently unrestrained and free to fly where it pleases. For an artist who kept moving most of her life, the image of a bird and its associated mobility surely had close personal associations. Wings over Water epitomises much of Frances Hodgkins’s oil painting technique in the 1930s and represents an important moment during the artist’s sojourn in Cornwall.