Anthony Van Dyck’s career in England coincided with the first output of large-scale, high-quality, figurative tapestries at the Mortlake manufactory near Richmond in Surrey, an extraordinary episode in English art.1 The history of the Mortlake tapestry manufactory was relatively brief: founded in 1619 by King James I and supported by the patronage of Charles, Prince of Wales, it was a quasi-royal enterprise with a distinguished courtly advisory committee, conceived on the model of, and in rivalry with Henry IV’s Parisian tapestry works founded in 1607.2 Its first director, the courtier and entrepreneur Sir Francis Crane, was responsible for finding the necessary weavers and equipping the buildings with looms. Its heyday, when lavish sums were spent on Mortlake’s luxury products, was the period prior to the Civil War. The factory was finally closed by Queen Anne in 1703. Given that artists of the stature of Raphael and Rubens, and many other artists besides, actively engaged in creating tapestry designs, it is not surprising that Van Dyck, during the course of his career, would be involved in some ways with the medium too. Van Dyck’s connections with tapestry, the traditional court art form par excellence, are few but there are some notable and compelling instances.

Mortlake’s foundation occurred when Van Dyck was a young rising star in Antwerp, and one wonders whether he was approached as a potential candidate to be the head designer of the new and prestigious enterprise. No document or work by Van Dyck relating to Mortlake exists. However, art historians Oliver Millar and Christopher Brown have both speculated that ‘Van Dyck may have been brought to England not as a portrait painter, but as a designer of tapestries’, which would have given him ample opportunity to produce allegories, mythologies and stories from the Bible.3 This tantalising suggestion deserves further examination.

At the time of Van Dyck’s first brief arrival in England in the winter of 1620–1 an order was made for a payment to him of £100, a ‘speciall service’ for James I.4 Nothing is specifically known of this, and the one-off payment has been the subject of much speculation. The amount was the same as he later received for the ‘Greate Peece’ of Charles I and Henrietta Maria and their Two Eldest Children 1632 (Royal Collection).5 In any case, only a handful of paintings from this period are known, and it is tempting to consider the payment was related to tapestry. According to Millar:

It is also conceivable that the King hoped to employ him at his newly established tapestry factory at Mortlake. At least one much less distinguished Flemish artist, Abraham van Blyenberch, was working at this period on designs for tapestries to be woven at Mortlake; and Van Dyck’s sense of linear design and his experience of designing for tapestry in Rubens’s studio would have fitted him perfectly for such a task.6

Millar goes on to remark of The Continence of Scipio (fig.1),7 painted during this first English interlude, that it ‘would be admirably suited for a tapestry’. Brown concurs:

While in Rubens’s studio in Antwerp, he was closely involved in the design of the Decius Mus tapestries and the painting of their cartoons. Buckingham was a supporter of the Mortlake tapestry factory and if we look at The Continence of Scipio it is difficult not to be struck by its frieze-like composition and two-dimensionality. Both are characteristics of Van Dyck’s style in Antwerp as well as in London and are especially appropriate to tapestry design.8

Despite also being offered an annual pension of £100, Van Dyck stayed only a few months in England. He returned to Antwerp, shortly afterwards going on to Italy, where he remained independent, receiving patronage in Genoa and inspiration from the works of Titian.

Fig.1

Anthony van Dyck

The Continence of Scipio 1620–1

Oil paint on canvas

1830 x 2325 mm

Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford

Van Dyck’s early career in the studio of Rubens had given him valuable experience as an all-round artist. Through his dynamic master, he learnt of the aesthetic and technical properties of the tapestry medium, and worked on the Decius Mus cycle, contracted to Rubens in 1616. In total, Rubens designed at least four major tapestry series over the course of his career, all with vast and complex designs challenging to the weavers.9 The Story of Decius Mus was the first of these, conceived by Rubens as small models, from which full-size final cartoons on canvas were subsequently made by Rubens and his assistants (those in the Liechtenstein collection are probably by Van Dyck and with substantial finishing touches by Rubens).10 Just as Van Dyck made scaled-down tonal grisailles for his master to be reproduced by printmakers including Lucas Vorsterman and Paulus Pontius, he was also entrusted with the difficult task of producing clearly articulated cartoons that could be translated by weavers into full-blown tapestries.

Rubens’s involvement with tapestry, a substantial and lucrative business centred in Brussels, may also have something to do with his ancestry. As the art historian Thomas Campbell and others have pointed out, his maternal grandfather, Hendrick Pypelinckx, and his son Dionysius were tapestry merchants in Antwerp.11 Furthermore, his father-in-law Daniel Fourment was also involved in the luxury textile trade and was a silk merchant. Similarly, Van Dyck’s personal background could account for an inherent sympathy, if not a predisposition for the textile arts. His father, Frans van Dijck, according to the biographer Giovan Pietro Bellori, ‘was a merchant of cloths, which in Flanders surpass all others in fineness and workmanship; his mother occupied herself with embroidery, and she painted with her needle, fashioning landscapes and figures in stitchery’.12

Van Dyck’s first-hand insight into the potential of the tapestry medium so early in his life would thus have given him a valuable skill that could easily have been transferred to his studio in Blackfriars and onwards to Mortlake. Before exploring why this did not happen, it is important to take a closer look at the development of tapestry in England in the years before and after Van Dyck’s arrival in London.

Tapestry production in England

Tapestry is a pictorial art and bears a close relation to painting. The medium is not so far removed from Van Dyck’s normal run of work, as producing designs required an artist to create preparatory drawings and sketches. A textile made from wool and silk, a tapestry has unique visual qualities, not forgetting insulation properties. The most ambitious tapestries conceived on a very large scale comprise multiple scenes that can accommodate complex iconographical programmes. In the late seventeenth century there was great variety in the types of wall coverings available to wealthy customers who could specially commission pieces bearing family arms. Woven hangings nearly always had pride of place in both private and public apartments, adding colour and interest to an interior, besides serving a practical purpose in insulating draughty rooms. Royal and rich, noble families took advantage of the portability of the tapestry and often owned large numbers, which could be transported as required from palace to palace and house to house. Sometimes their use was seasonal, with heavier tapestries covering the walls in winter and replaced in summer. They were deployed in courts throughout Europe, frequently for ceremonial events or given as diplomatic gifts. Some of the best and grandest tapestries were specially commissioned, invariably by the most notable patrons, and designed by renowned painters. Their architectural elements, usually combined with ornamental decorative borders, contribute greatly to their appeal. They are also intriguing, because they exist in multiple forms; sometimes one can be identified as the first weaving, rather like paintings that exist in differing versions. Many tapestries have workshop or makers’ marks, initials and monograms or crests, and deciphering these and establishing the provenance, as for paintings, is invariably instructive.

Fig.2

Wenceslaus Hollar

Coronation of Charles II in Westminster Abbey 1662

Etching

378 x 483 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

In a letter to the English diplomat and art agent Sir Dudley Carleton in 1618, Rubens wrote, ‘one evaluates pictures differently from tapestries. The latter are purchased by measure, while the former are valued according to their excellence, their subject and the number of figures’.13 This is a significant remark providing a direct insight into contemporary attitudes towards tapestry, but as Campbell has pointed out, while correct in a ‘basic sense’, Rubens’s comment simplified the issue and in fact tapestries were far costlier than paintings and esteemed as palatial fixtures.14 Besides their size (measured in Flemish ‘ells’), a prime factor of the most luxurious examples was the choice of materials. The quality and strength of the dye-coloured threads was important, as was the delicacy and density of the weave. Precious, gilt-metal-wrapped threads, for instance, were affordable only by the richest, often royal, clients. Unfortunately, tapestries are particularly prone to exposure from light and dirt and are thus rarely encountered in their original vibrant colour and splendour.

Modest and functional textile hangings, carpets and embroideries were widespread in England. Prior to Mortlake the only significant tapestry manufactory were the workshops established sometime before 1570 at Barcheston in Warwickshire by William Sheldon.15 Sheldon’s master weaver was Richard Hickes, who was of Flemish origin and whose surname was likely an anglicised version of Van den Hecke: he was one of many skilled émigré weavers from the Low Countries who arrived at this time.16 The Sheldon tapestries are sometimes figurative, but arguably the best works are a series of county maps from the 1590s, based on the work of the cartographer Christopher Saxton. 17

Among the most famed tapestries in England was the ten-piece Story of Abraham set of arras hangings woven with gold that belonged to Henry VIII, delivered from Brussels in c.1544 and hung at Hampton Court Palace outside London.18 They were woven in the workshop of Willem de Kempeneer in Brussels, from designs attributed to the painter Pieter Coecke van Aelst. They are probably the indistinct tapestries that feature in Wenceslaus Hollar’s etching of the Coronation of Charles II in Westminster Abbey (fig.2), which took place on 23 April 1661, and they were certainly used for the coronation of James II in 1685 and subsequent monarchs.19

Fig.3

Wenceslaus Hollar

Trial of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury 1644

Etching

183 x 138 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Another renowned cycle of tapestries were the Armada series, celebrating the famous naval victory over the Spanish in 1588, commissioned in 1592 by Lord High Admiral Howard.20 The maritime artist Hendrick Vroom made the designs based on charts by the architect Robert Adams. The sumptuous tapestries were woven in François Spiering’s workshop in Delft.21 They also feature in an etching by Hollar, the Trial of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury 1644 (fig.3), where they are mentioned in the print’s key as ‘The Hangings of 88’.22

Fig.4

Sir Francis Crane c.1626–36

Mortlake tapestry

1575 x 1400 mm

Ingatestone Hall, Essex

The Mortlake manufactory prospered under the ownership and direction of Sir Francis Crane.23 He frequently complained of his debts, owing to the less than prompt payments of his clients, but he nevertheless became enormously rich and acquired a number of estates from the King in 1629, building himself a new house at Stoke Park in Northamptonshire; he was also granted a joint patent to issue farthing coinage.24 In the panelled dining room at Ingatestone Hall, Essex, is an unusual and yet appropriate tapestry: a portrait of Crane surrounded by an elaborate trompe l’oeil carved and gilded auricular frame (fig.4). It was perhaps made as a vanity project, celebrating both Crane’s position as tapestry director and his role from 1628 as Chancellor of the Order of the Garter, but it may be conjectured that it was also an important experiment in the suitability of tapestry for portraiture. The tapestry portrait has been associated with Van Dyck and perhaps records a lost work, but it may well be after another artist, possibly Daniel Mytens or Cornelius Johnson. Oliver Millar describes it summarily and in a non-committal way as ‘three-quarter-length in a Van Dyckian pose’.25

Another supporter of the Mortlake factory in its early years was the ubiquitous George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, favourite of King James I and Prince Charles.26 His residences, chiefly York House on the Strand, required art and furnishings befitting his power, rank and wealth. His collection of Italian paintings is well known, formed mainly with the help of the art agent Sir Balthazar Gerbier, but he also possessed some substantial tapestries.27 He owned, for example, a set of the Mortlake Story of Vulcan and Venus tapestries, which are now in the Royal Collection in Stockholm. These are embellished in the side borders with the Villiers arms and the Order of the Garter around an anchor and reflect his plethora of titles and offices: he was a Knight of the Garter and Lord High Admiral. Among the other tapestries that he acquired (but did not necessarily pay for) from the newly established Mortlake manufactory were a series of The Months and a series on the Story of Solomon and Sheba. Designs for these tapestries, which were already in production by 1623, were all adapted from sixteenth-century Brussels tapestries or ‘old patterns’. They very likely derive from sets formerly belonging to Henry VIII, and some motifs can be recognised from Italian engravings, the manufactory having no official designer before the arrival of the German artist Francis Clein (1582–1658) in late 1623.

The pinnacle of Mortlake production was the series of eight tapestries after Raphael’s cartoons for the Acts of the Apostles. Raphael’s famous designs were first commissioned by Pope Leo X for tapestries in the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.28 Seven of the original cartoons were purchased in 1623 by Charles, Prince of Wales (soon to be King Charles I), now displayed at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. From these an eight-piece set of tapestries was made for Charles bearing the Royal Arms (subsequently acquired by Cardinal Mazarin and Louis XIV and now in the Mobilier National in Paris).29 Margaret Whinney and Oliver Millar have said of this set that ‘even in its present faded condition, [it] gives perhaps a truer impression of the magnificence which Charles I loved than any surviving works of the period except for the grandest of Van Dyck’s portraits and the Rubens ceiling at Whitehall’.30

Rather than Van Dyck, Charles I secured the services of Francis Clein as resident designer at Mortlake.31 In 1625 Clein was employed to copy Raphael’s cartoons and create new borders. Subsequently, he designed another homogeneous cartoon for the series, the Death of Sapphira, a pastiche of Raphael. Apart from the primary Royal set, other prestige sets were acquired by Henry Rich, Earl of Holland, and Philip Herbert, Earl of Pembroke.32

Clein was a talented artist capable of applying himself to a variety of work. The art historian Edward Croft-Murray has said ‘[he] verges on a weak imitation of Rubens’, whereas Wendy Hefford has sprung to his defence, recognising ‘powerful designs that best exemplify the spirit of the Baroque in English tapestry’.33 Born in Rostock, his formative artistic years were spent in Italy. Clein subsequently worked for Christian IV of Denmark (the uncle of Charles I) at the court in Copenhagen.34 He was no doubt invited to London under the auspices of the English envoy, Sir Robert Anstruther, and lured with a pension of £100 per annum. As one of the few sophisticated continental artists, he was held in high regard, and after Charles I acquired the factory in 1637 he was allocated £250 per annum for himself and an assistant. Payments ceased in 1642 due to the Civil War and Clein sought alternative artistic employments.35

Once in London, he worked on an assortment of tasks and this is detailed in a remarkable document in the National Archives, giving payments and a list of works executed by him for King Charles probably during the year 1625.36 This includes drawings for the adornment of a Triumphal Arch under the supervision of Inigo Jones. Also listed are ‘divers patternes one on both Sides for the greate Seale’, the design of which is usually associated with Nicolas Briot.37

In addition, the copies of two of the Raphael cartoons are itemised: The Death of Ananias and The Blinding of Elymas. Further intriguing work documented is a crucifixion in the Catholic Chapel Royal at St James’s Palace and the decorative scheme for the Queen’s Cabinet at Somerset House. And so, in addition to the annual gratuity, Clein received piecework payments. One is reminded here of the diverse tasks that Van Dyck was given under the vague terms of his royal employment extra to portraiture, such as the chore of repairing one of Titian’s Emperors from the Mantuan Gonzaga collection. Van Dyck did not work exclusively for his royal patrons and he also had the freedom to take on other outside, but mostly courtly, portrait commissions.

Clein’s first great success once he became resident artist at the Mortlake factory was the series of Hero and Leander.38 Another very fine series designed by him is the rare set of Horses, of which one early example of Perseus and Andromeda is in the Victoria and Albert Museum.39 Lacking a border, although the gilt metallic thread suggests a Royal commission, it is of unknown provenance.

However talented Clein certainly was, it is still a wonder that a more precocious artist was not chosen as the first chief designer at Mortlake, given the considerable investment in the manufactory and the high hopes for its success. The project required considerable management, undertaken by Crane, and was labour intensive requiring fifty Flemish weavers and their families to move to Mortlake, lured with the help of William Trumbull, the resident English agent in Brussels. Among the new denizens was Philip de Maeght, who was the overall director of weavers.

Another possible contender for the prize position of Mortlake designer was the Italian artist Orazio Gentileschi. There is a reference in the inventories of Charles I’s art collection by Abraham van der Doort to ‘A Book of Drawings’, with tapestry designs, presented to the King by Gentileschi, no doubt a speculative bid to ingratiate himself and gain further employment.40 In 1626 Gentileschi was granted an annual sum of £100, on a par with Clein. Why, then, when Van Dyck was eventually lured back to London in 1632, knighted, given a gold chain, a house and royal appointment as ‘principalle Paynter in Ordinarie to their Majesties’, was he not called upon to produce innovative tapestry designs of more testing subjects, in addition to his prime duties as royal portraitist? It is all the more extraordinary given that artists of the stature of Jacob Jordaens and Simon Vouet also worked in the field of tapestry, seemingly without hesitation and arguably producing some of their best work.41

Sir Francis Crane died in 1636 and the Mortlake factory passed to Richard Crane, his brother and a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber. Within a year, it was acquired by Charles I, on 13 April 1637, and restyled ‘The King’s Works’. Sir James Palmer, a Gentleman of the Bed-Chamber, was appointed ‘Governor of His Majesty’s Tapestry Works at Mortlake’; his monogram was subsequently incorporated on the Mortlake products.42 Palmer was an accomplished amateur miniaturist and also an art collector. He ingratiated himself to the King by presenting to him the Wilton Diptych, now in the National Gallery, London.43

Fig 5

Josias English

Supper at Emmaus (after Titian) c.1649–56

Etching

218 x 278 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

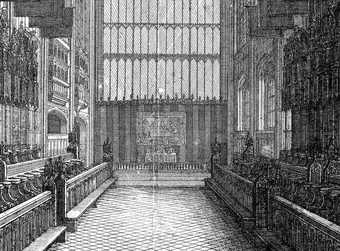

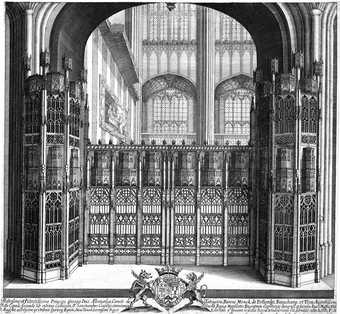

Certain Mortlake tapestries were based on works in the King’s collection of pictures. This includes ‘A Mantua peece Done by Tichian’, the Supper at Emmaus c.1535 (Musée du Louvre, Paris), that once hang in the First Privy Lodging Room at Whitehall.44 The Titian painting was bought by Robert Houghton in October 1651 for £600 at the Commonwealth sale, and was eventually acquired by Louis XIV in 1662 from the art collector Everard Jabach. The earliest surviving tapestry version of this single composition, bearing the early marks of Crane and De Maeght, belongs to St John’s College, Oxford.45 There is no crest to provide a clue to the commission, but it is possible that the tapestry is connected to Archbishop Laud, Chancellor of the University at this period (1630–41). Laud studied at St John’s College and was later made President (1611–21). During his tenure the Canterbury Quadrangle was built at his expense. He added to the fabric of the chapel and donated to the library and in 1633 he commissioned the French sculptor Hubert Le Sueur to make statues of Charles I and Henrietta Maria, which were installed in 1636. The tapestry hangs in the staircase in the President’s Lodgings. There is also a later example at St George’s Chapel at Windsor, recorded in an inventory in 1667, which was given by Lady Mordaunt, wife of John, Viscount Mordaunt, constable at the castle after the Restoration.46 The work is the subject of a rare contemporary etching by Josias English (fig.5), who signed it ‘de Mortlake’, although little is known of his career and his precise Mortlake connection.47 The print is unusual as it reproduces the tapestry rather than the painting, although it lacks a distinctive tapestry border. The tapestry also features in situ in two prints by Hollar, which is a reminder of the enduring liturgical role of tapestry and the controversial Laudian innovations, which led to a revival of images and ornaments, rich fabrics and precious plate.48 It can be seen behind the high altar in a print dated 1663, showing the extent of the choir and its remarkable stalls (fig.6).49 It is most clear in the print of Edward IV’s tomb and can be seen in the background on the wall (fig.7).50

Fig.6

Wenceslaus Hollar

Detail from Interior of St George’s Chapel, Windsor 1663

Etching 300 x 330 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.7

Wenceslaus Hollar

Tomb of Edward IV, Windsor c.1665–6

Etchng

300 x 325 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

The sales of the King’s goods following his execution in 1649 resulted in the dispersal of his magnificent collection of paintings, but great quantities of sumptuous antique and contemporary Mortlake tapestries also went to France and Spain.51 Cardinal Mazarin was a particularly eager buyer and received intelligence of what was on offer through memoranda from his agent; likewise the Spanish diplomat and art agent Don Alonso de Cárdenas developed a keen eye for the tapestries and resorted to subterfuge in acquiring them and sent them off as cargo in crates to Luis de Haro, Marques del Carpio, principal minister to King Philip IV.52 Some of the more important tapestries were nevertheless reserved for the use of the Lord Protector.

Although work continued at Mortlake during the Civil War payments through the Exchequer were ended and the weavers suffered through lack of patronage. Mortlake survived the Interregnum (1646–60), but the history of the factory is more difficult to reconstruct following the death of Charles I. Under the Commonwealth, the works were put into the charge of Sir Gilbert Pickering, a member of the Council of State and later Lord Chamberlain to the Protector, and Philip Hullenberch became the chief weaver. In 1653 the Council of State ordered that Mantegna’s monumental The Triumphs of Caesar should be delivered to Pickering, so that copies should be made for use as cartoons for tapestries.53 For some reason the project faltered, although a set of such tapestries are extant at Bowhill House, Selkirk, in the collection of the Duke of Buccleuch, but these are datable to the 1670s, probably made for Ralph, 1st Duke of Montague who later also took charge of Mortlake and held the position of Master of the Great Wardrobe.54

Van Dyck and English tapestries

Returning to the specific subject of Van Dyck and tapestry in England, one of the first paintings by Van Dyck with a possible tapestry connection is the Continence of Scipio, a key history painting from his first brief arrival in England over the winter of 1620–1. Despite its undoubted qualities in terms of ‘excellence, subject and number of figures’, the precise details of its commission and purpose have proved elusive. Nevertheless, the appealing idea that this was the ‘speciall service’ for which the artist was paid £100 from the royal accounts on 17 February 1621 is repeated again by Oliver Millar in his final word on the matter to his entry on the painting in the Van Dyck catalogue raisonné of 2004: ‘If plans for Van Dyck to design a tapestry, or a suite of tapestries, for the King proved abortive, the King could have handed over to Buckingham at least one surviving work which might have been associated with them.’55 John Peacock has analysed the theatricality of the composition, arguing that it is ‘knowingly adjusted to the indigenous theatrical tastes of the Jacobean court’ attuned to the love of plays and masques. It is also noticed ‘His picture weaves emblematic and mythological elements into its historical theme’, in an unconscious nod to tapestry.56 The scintillating colours and the lavish garments of the protagonists and the carpet at their feet also celebrate the tangible properties of textiles, a fitting theme for a tapestry. The Solomonic columns in the background also recall the Raphael cartoons, but the derivation is indirect and Van Dyck’s source is more likely via Rubens.

Fig.8

Anthony van Dyck

Charles I and the Knights of the Garter in Procession c.1639–40

Oil paint over silverpoint on panel

292 x 1308 mm

Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Another key work by Van Dyck which can be associated with tapestry is the grisaille oil sketch of Charles I and the Knights of the Garter in Procession (fig.8), showing the annual event held on St George’s Day, 23 April.57 It was probably painted in 1639 or 1640, towards the end of Van Dyck’s life. Bellori, whose main informant was the courtier Sir Kenelm Digby, provides the earliest description of the project. According to this account, Van Dyck was in negotiation with the King to provide tapestry designs for a project related to the history and ceremonial of the Order of the Garter to cover the walls of the hall of state in the Banqueting House at Whitehall, to hang beneath Rubens’s great painted ceiling celebrating the reign of James I installed in 1636. This would have been especially appropriate, since the space was also used for the St George’s day celebrations (although this event was later transferred to Windsor). It is also relevant to note that the sumptuous Story of Abraham tapestries were used to decorate the Banqueting Hall in 1635 for this very same event.58 However, the art historian Wendy Hefford is sceptical about the suitability of the Ashmolean sketch for a tapestry:

Bellori, however, may have mistaken the medium. Van der Doort, who was well informed concerning the connection of other works of art with Mortlake, called Van Dyck’s sketch merely ‘a model for a bigger piece’; and Horace Walpole, in his Anecdotes of Painting, described this sketch as part of a plan, proposed through Digby, to paint the walls of the banqueting House in Whitehall. The design, moreover, would have been impracticable to weave, with lifesize figures occupying under one third of the height.59

Bellori’s account is nonetheless still very informative. He described with sympathy the painter’s declining health and his ‘yearning to retire from the continuous routine of portraits and pictures to devote himself to a peaceful project, away from the bustle of the court, which would at the same time bring him honour and profit; and in order to leave a memorial and fame for his merit’.60 In terms of ‘honour’, Christopher Brown points out that Van Dyck was endeavouring ‘to expand his reputation and enter into artistic emulation with his predecessors’ and tellingly of ‘his sense of frustration at being confined to portraiture and his wish to undertake a major decorative scheme’.61 But the ‘profit’ aspect seems to have proved a stumbling block and the King baulked at Van Dyck’s asking price and with the artist’s death in 1641 that was the end of the matter.

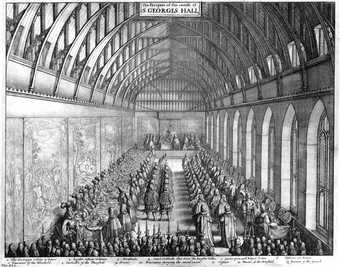

The Order of the Garter, founded during the reign of Edward III, was the most elite chivalric body in England. It was a ripe subject for artists, and under the personal rule of King Charles I the potency of the pageantry was fully exploited. There are forebears to Van Dyck’s oil sketch in the shape of Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder’s print of the procession in 1576,62 and Sir Peter Lely, who subsequently owned Van Dyck’s sketch, made some vivid drawings of the Knights and various officers involved, likewise for an unrealised project.63 Many of Van Dyck’s portraits are of Garter Knights, and they invariably flaunt the gold, enamelled and gem-encrusted jewel badge hanging from a blue sash, vying with the numerous non-English portraits of members of the Order of the Golden Fleece. For the processions, Knights wore full regalia, robes and a hat adorned with ostrich feathers, and headed to St George’s chapel for a service and then onwards for a feast. Elias Ashmole, Windsor Herald at the College of Arms in London, wrote a study of the history of the Order, publishing his lengthy, definitive chronicle The Institution, Laws and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter in 1672, which also codified the precise and appropriate rituals. The volume was lavishly illustrated with numerous plates by Hollar, and one of these shows the banquet in St George’s Hall (fig.9).64 In Hollar’s image of the capacious vaulted hall can be seen ‘The Soveraign [sic] sitting at dinner’ at the far end under a throne baldachin on a raised platform and surrounded by an overwhelming tapestry scheme that includes battle and hunting scenes, which remains to be identified, but is certainly not designed by Van Dyck.65

Fig.9

Wenceslaus Hollar

Banquet in St George’s Hall, Windsor c.1663–72

Etching

300 x 375 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

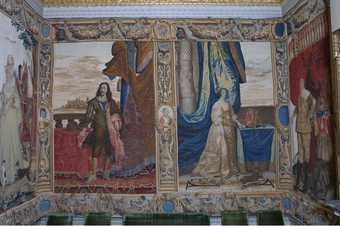

Inevitably, some of Van Dyck’s paintings were made into tapestries but this occurred posthumously. Well into the period of the Restoration, some of his royal portraits were turned into tapestries and form a set known as the Kings and Queens, which now hang in the dressing room at Houghton Hall in Norfolk, the seat of Sir Robert Walpole, England’s first ‘Prime Minister’, and in the care of the Victoria and Albert Museum since 2002. They bear two sets of initials and the date 1672; those of Francis Poyntz, who held the post of Yeoman Arrasworker at the Great Wardrobe, and James Bridges. 66 The set is unique and bears the royal arms of Charles II. Finely woven, with much gold, and with very grand borders featuring putti and swags they are still in the great Mortlake tradition. The five royal portraits are all based on paintings in the Royal Collection and emphasise the Stuart dynasty. They include James I, Charles I’s father, after the painting by Paul van Somer, which was copied by Van Dyck. In the background is Windsor Castle and at either side are roundels of Prince Henry and Prince Charles. Anne of Denmark, Charles I’s mother, is after a painting by van Somer of 1617: she is dressed for hunting, with Oatlands in the background. Christian IV, Charles I’s uncle, with his distinctive pigtail, is based on a portrait by Karel van Mander the Younger. Charles I’s portrait is derived from the ‘Greate Peece’ (fig.10). This has a vignette of Parliament House and Westminster Hall and the cluster of buildings comprising Whitehall but is not a direct copy: instead, it is adapted from the painting as Charles is standing rather than seated. The carpet and drapes are very prominent. It also features at the sides two roundels with portraits of the young sons, Charles and James, the Prince of Wales and Duke of York, based on the painting by Van Dyck of Charles’s three eldest children. Finally, Henrietta Maria is modelled on Van Dyck’s painting of 1632, but is again adapted to a full-length. The addition of the twisted Solomonic column at left from Raphael’s cartoon of The Healing of the Lame Man is a pure Mortlake touch.

Fig.10

Charles I and Henrietta Maria (after Van Dyck) 1672

Mortlake tapestry

Houghton Hall, Norfolk

© V&A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

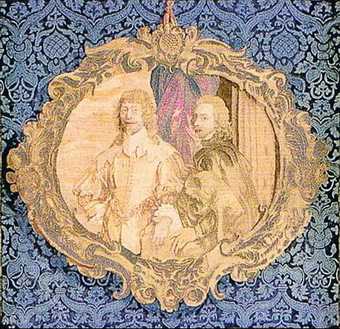

Fig.11

Sir Anthony Van Dyck with Endymion Porter (after Van Dyck) c.1633–49

Mortlake tapestry

Knole, Sevenoaks, Kent

A Mortlake tapestry at Knole in Kent (fig.11), hanging in Lord Sackville’s private quarters, copies Van Dyck’s oval friendship portrait, his self-portrait with Endymion Porter, now in the Prado in Madrid.67 It is suggestive of what might have been a much more fruitful encounter between Van Dyck and the applied arts. Little can be said of its genesis and sadly, it is in very poor condition and has faded. The auricular frame surmounted by a sunflower – a motif often used by Van Dyck – recalls the frame surrounding the tapestry of Sir Francis Crane, and is also interesting as it possibly records the original picture frame.68

The simple answer as to why Van Dyck does not appear to have made more designs for tapestry perhaps owes something to the technical difficulties that his painterly style presented to the weavers. That Van Dyck seems to have been more or less exclusively absorbed in royal and aristocratic portraiture from 1632 onwards, managing a remarkable workload and that Charles I was latterly chronically short of money also conspired against any involvement in tapestry or grand-scale woven paintings. Above all, Van Dyck was subject to the whim of Charles I who seems to have ‘rest[ed] content with the work of Frances Clein’. 69