Adrian Searle

The first time Luc Tuymans showed in Britain was 1994 in Unbound: Possibilities in Painting at the Hayward Gallery. He was already extremely well known in Europe and had a totally developed sense of his identity as an artist. He seemed to blow away the last cobwebs of Britain’s inward-looking or America-looking sense of what the agenda was for being a painter.

Peter Doig

Yes, when Tuymans emerged there weren’t many new contemporary painters making, or using imagistic paintings, except perhaps John Currin. At that time in the UK, a lot of work was highly polished; process-based and very clean. So it was quite shocking to see Tuymans’s paintings, but also very refreshing and unexpected because of the scratchy way they were made. They also seemed to be created out of necessity, rather than to fill a niche.

Adrian Searle

You mean the roughness, the small scale, the bad paint?

Peter Doig

And the subject as well. The fact that there was a subject, and an implied narrative.

Adrian Searle

Was that because people said you couldn’t do that any more?

Peter Doig

I don’t know. Maybe people felt embarrassed to do it.

Paulina Olowska

What appealed to me when I saw this work for the first time was its classic quality, the misleading idea of colour and tightness of form. I was also amazed how students reacted to it. Painting was not considered a serious medium at the time, but somehow, seeing his work, it gave hope to painting. Some, of course, took this reference too closely, so much so that their work soon looked like his.

Adrian Searle

One of the things Tuymans said was that he wanted to avoid cultivating a style or an expressive approach at all costs, but the way he has painted has been turned into a style by lots of lesser artists. And that seems to me to be an entirely negative thing to have happened. I don’t want to see another Luc Tuymans as long as I live.

Chris Ofili

However, I think one’s work has to come from somewhere. Either it drops from the sky, or you’re influenced by something that leads on to other things. A lot of Luc Tuymans’s work derives in look and feel from Raoul De Keyser, even though the subject matter is very different. You can see that Tuymans would find him interesting.

Paulina Olowska

There is also a connection with the Dutch painter René Daniëls. The works of both Daniëls and Tuymans are investigations into the method and approach to painting as a subject. Their paintings are dealing with reality by way of an illusionism of space and an economy of paint, and they have a kind of distance to reality. Also the idea that the image is not representing what it seems to be, but it is dealing with something else.

Peter Doig

I think there is something about the part of the world that Tuymans comes from [Belguim]. There’s a certain kind of painting that maybe we weren’t aware of here that has been going on for some time.

Adrian Searle

Yes, and also connections between artists. De Keyser is quoted in paintings by other artists, and he has quoted René Daniëls – and they have both referred back to the Belgian Symbolist Léon Spilliaert, a completely unknown figure in Britain.

Paulina Olowska

And how about Morandi?

Adrian Searle

Tuymans wrote somewhere that he thought Morandi was ‘poetic bullshit’.

Paulina Olowska

That’s terrible.

Chris Ofili

I think Tuymans has a habit of making brash statements. You can say Morandi is ‘poetic bullshit’, but it’s just muscle flexing. Tuymans though, is a poetic painter.

Paulina Olowska

He is poetic, but he has a very specific idea about what poetic means. Anything can be poetic, and poetry can be violent. A bouncer can be a poet. He was a bouncer himself, was he not?

Adrian Searle

Yes, he used to tell everyone that story.

Paulina Olowska

He loves anecdotes. What do you think of his idea of anecdotes in connection to the actual work?

Adrian Searle

There is the idea that there is a lot in the painting which you can’t see, which is not visible. And there are stories that are not in the images. Or they are only in the images after he’s told you what the story is. One of the things that strikes me as very important about Luc’s work is that he makes the interior monologue visible. The problem with a lot of British painting, certainly in the 1970s–80s, was that you weren’t allowed an interior monologue unless it was completely solipsistic; unless it was completely to do with some invented mythology. And his monologue deals with painting, with history and with autobiography. But in a distanced, and what might seem cool way. Not that I’m sure it is that cool.

Peter Doig

He puts a lot into how you read the work through the titles of his paintings, doesn’t he?

Adrian Searle

A title can be an integral part of the work. Some artists use them as labels. As Duchamp said: ‘It’s another colour on your palette.’ These are all things that Luc has brought back to painting. Things that we lost because we thought they were redundant or uncool, or they had an air of academicism or something small and inoffensive.

Peter Doig

In terms of his content though, I like the way he can sometimes bring the sinister to something that appears quite innocuous. I remember seeing this painting The Architect 1997. There is an image of a man with a mask-like face on skis, lying on a massive field of white. It was painted from a still taken from home film footage of Albert Speer while on a skiing holiday in the Alps. It was made to connect with other paintings it was exhibited with – paintings of prison camps among them. There was something in the text for the exhibition about a telegram from Speer to Himmler complaining that the prisoners had too much space.

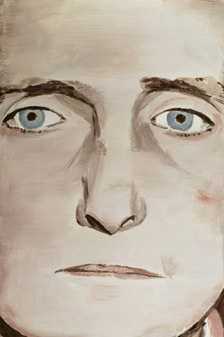

Luc Tuymans

The Diagnostic View IV 1992

Oil on canvas

57 x 38 cm

© Private collection, long-term loan to the Pont Foundation

Adrian Searle

You need the story in a way. You need to unpack it. In the same way you need to unpack history paintings, or perhaps most figurative art.

Chris Ofili

There is definitely a difference between spoken words and the painted world, but I think Tuymans exploits the two. He talks very well about his work. Often the world that he paints is very different from the world he speaks about. He may talk about violence, but when you look at a painting, it can appear very romantic, such as his precise image of flowers in a vase. I don’t really feel that I have to read the things in the paintings that he speaks of.

Adrian Searle

But the woman who put the flowers in a vase could have strangled her children, and the ashes of her dead husband who she always hated are actually also in the bottom of the vase…

Chris Ofili

It is a stance, but I think he does reveal things about the real world. I was looking at a book on his work and at the same time on the news was the story of the trial of the Belgian paedophile Marc Dutroux, and I was thinking: ‘God, this is actually like his work.’ As Peter said, on the surface everything looks absolutely fine, but there’s this entire undercurrent. His paintings seen as a whole allude to that sense of violence and complete a more intricate picture.

Paulina Olowska

When you talk about aggression, roughness, violence and anxiety in a work like this, it gives it another layer, but how do the two layers connect? I am interested in ambiguity in paintings so that it is often impossible to say what is the correct interpretation. In a way, I give an image time to breathe and then see if the connection comes later, never providing a definitive statement. Luc’s explanations are very direct. I don’t understand the way he talks about drawing and painting as separate media.

Adrian Searle

Drawings are always preparatory for the painting, aren’t they? Either that or they are made autonomously. Most of his paintings are actually planned out completely in drawings before they are made.

Paulina Olowska

It’s about the way he paints – having the unstretched canvases on the wall.

Adrian Searle

Many painters did that. Even Titian. Those canvases weren’t stretched. They were like animal skins and were stretched temporarily on a frame and then later put on a stretcher.

Paulina Olowska

Okay. I have this quote. He says: ‘Because of the unstretched canvases, the physicality of the work is in keeping with the space. That is electric.’

Adrian Searle

Which means that they are contiguous with the wall when he’s painting them, doesn’t it?

Paulina Olowska

Then you control the composition completely, as a painter.

Adrian Searle

Do you think so?

Paulina Olowska

If you unstretch the canvas and you cut, you make the composition after.

Adrian Searle

He’s not talking about cropping the painting. I remember seeing how Luc used to paint in this dismal apartment he had in Antwerp, with this crashed-in ceiling and wretched bed. I’ve seen paintings on the wall unstretched, but even then they were drawn out; the rectangle of how they would fit the stretcher was already drawn on the canvas. So they’re not cropped from bigger compositions. He knows exactly what size beforehand. The canvas is tacked to the wall, against a hard surface, which I think makes a difference to the touch of the painting, but they’re not actually on the stretcher.

Paulina Olowska

All right.

Adrian Searle

Do you find his paintings uninteresting?

Paulina Olowska

I found them inspirational, clever and quite intriguing. He proposed a new representational way of painting – painting with a kind of elegance.

Chris Ofili

Do you see that as being more European?

Paulina Olowska

I don’t know if it’s more European, but at that time it was something that wasn’t shown at all.

Chris Ofili

I was actually surprised how much work there is, the variety of images this guy comes up with – from tea pots, to people’s faces, to hands, to historical subjects.

Paulina Olowska

Are you suspicious that he seems to find so many subjects?

Chris Ofili

When I first saw the work I thought they were very strange paintings because each one had an individual life of its own. Now it feels like it has more to do with making more paintings that have more of a generic look to them. They all look as though they’re made in a hurry, but with an immense attention to detail at the same time. I think that’s quite a difficult thing to achieve. Philip Guston also achieved that wet-on-wet, speed of execution without wanting to miss out on anything. Like a greedy man in a hurry. You get a feeling he has so many more subjects to paint. And they do look like paintings of a person that enjoys the process of putting paint on to a surface.

Adrian Searle

But he’s not a joy-of-paint merchant.

Chris Ofili

I think his paintings are evidence of beautiful acts, rather than violent, ugly acts. Maybe there’s a pleasure in inflicting violence, but I don’t see violence as a beautiful act.

Adrian Searle

Can’t violent acts be beautiful too?

Chris Ofili

It depends on your taste.

Adrian Searle

Where do we imagine the violence is?

Paulina Olowska

A friend of Tuymans said: ‘Everything we touch from the past is an access to death.’

Adrian Searle

A lot of the things he has said, and have been said about him, are elliptical.

Chris Ofili

It depends on what books you read. This guy that paints will also read books on philosophy, and he’s thinking about that world. I don’t know how relevant that kind of statement is to his paintings.

Peter Doig

It depends what you want. Do you want the statements, or do you want the paintings? I know you can have both, but in the end you’re standing in front of a painting and looking at it, aren’t you? Do you want to be diligently reciting his statements at the same time, remembering all those things that he said about the paintings? Or are you prepared just to take on board what you see and actually find out how that affects you? Ultimately, I think that’s the test of whether it’s a good or great Tuymans painting, or any painting actually.

Chris Ofili

Yes. If you go to the National Gallery, for example, none of those guys is there with you. All that’s left is the painting. But I think there’s a danger, because when you read what Luc says, it all seems so coherent, so focused, and it has to add up to something.

Peter Doig

I don’t think he’s really like that. I think he uses words like a foil. Maybe words fill in spaces left blank by the paintings. I like the idea that Luc’s show is twinned with Edward Hopper at Tate Modern – there was a series of his pictures somewhat based on Hopper paintings. There are similarities between the two artists, but I don’t think Tuymans’s work is as melancholic as Hopper’s. Tuymans’s painting appears to be more about a dissolved memory, rather than a present condition. Both artists’ work seems to evolve from what is inside the head, and, although made quite differently, it still ends up having the same sort of mood.

Adrian Searle

Really? For me, it is the melancholy and the solitude that you feel when you look at them that really matters – in both artists. Hopper is more about melancholy and Luc is more about emptiness.

Paulina Olowska

I think also that Tuymans’s work is more about the object, while Hopper’s is more about the image.

Adrian Searle

One thing Hopper wasn’t afraid of was the charge of being illustrational, and I guess Tuymans also takes something from the genre of illustration, almost as an antidote to expressiveness. His paintings are also less tethered to their subjects than, say, Richter’s October 18, 1977 series, which are more like history paintings than anything Tuymans has done.

Chris Ofili

Yes, I don’t really see Tuymans as a history painter. I think he’s someone that looks at subjects and looks at history, but doesn’t get truly involved. Paintings such as Mwana Kitoko, the portrait of King Baudouin, or Lumumba (both from 2000) don’t really engage with the subject. I think they are documentaries of documentaries.

Paulina Olowska

It relates to how he crops the image. Tuymans zooms into it, while Hopper completely extends it the other way, just to focus on the story of the picture. The paintings can look as if they are being erased in a way.

Adrian Searle

He has said that much of painting is about emptying, and bleeding out the image. There is a link with how he uses colour too. It has a certain flavour – wanting paintings to look already old, slightly unclean. And that has got a lot to do with taking images from Polaroid photographs, using images degraded via multiple-generation photocopies, so that they become overexposed, as in a painting such as Drumset 1998. He is also acknowledging how images are mediated. But instead of using the mass image as a symbol of mediated experience, he’s dealing with the degraded image or the remnant, the fragment, the leftover.

Chris Ofili

Maybe he doesn’t want too much paint.

Paulina Olowska

I prefer his paintings of still life – the sunset, or the portrait – since in a way they deal directly with the history of painting and are much more open for interpretation. This is why I come back to Morandi…

Luc Tuymans

Gas Chamber 1986

Oil on canvas

50 x 70 cm

© Collection Museum Overholland, Amsterdam

Adrian Searle

But in a painting such as Gas Chamber 1986, which I think everyone would agree is a key image in his elevation as an artist, do people get confused between the subject and the work? They think ‘that’s a gas chamber, which is really awful and sad’, and therefore believe they’ve got an awful, sad painting. They confuse the painting and what it depicts, and what the act of depicting signifies.

Peter Doig

It’s a difficult one, isn’t it?

Adrian Searle

Yes. The idea of repression seems to be floating around here. I was born two or three years before Luc – in Britain, not in Belgium – but in conversations with artists and writers of the post-war baby boom generation of the early 1950s, everyone talks about growing up in a stifled atmosphere where things were never discussed. And in a way, I think, there’s an autobiographical element in the work that has to do with that.

Paulina Olowska

But then it always becomes so idealistic. I like the relationship between the spoken word, the stories and the paintings – and maybe it should come with a bit more irony or distance?

Chris Ofili

That’s the case with some of the characters of his paintings. But I don’t know if that’s necessarily the case with him as a painter. I believe there has to be a separation between what he paints and that world, and how he is. And sometimes, Paulina, I think you’re talking about him mostly, perhaps because you know him. Often you’re not talking about the paintings. I think you mix the two.

Paulina Olowska

I do it on purpose because so much is written about the works, so maybe it’s more interesting to talk about the meaning of his work in general and what was written and said about it.

Peter Doig

It all starts off with what he says, doesn’t it? If he hadn’t said anything, there’d be nowhere for people to start. I find everything I read about Tuymans’s work essentially starts from his mouth.

Adrian Searle

The paintings would probably be taken in a slightly different way if he said he read Stephen King and watched crappy, gung-ho war movies. But essentially, it has got to be about how one looks at the world. And one of the good things about Tuymans’s influence is that he has given people permission, in a way, to take subjects from absolutely anywhere. He also makes you think about the difference between a painting’s subject and its content. His art is filled with ambiguity and ambivalence.

Peter Doig

Maybe this isn’t an absolutely new concept – Manet did the same I think – but Tuymans has helped to open up the way artists can discover new subjects and re-evaluate old ones. In this way he has been responsible in affecting how a lot of new art is made.