Flamboyant. Extravagant. Extroverted. Eccentric. Megalomaniac. Alcoholic. Sexually obsessed. Manic-depressive. Bohemian. There are as many stereotypes as there are anecdotes about famous artists. The inevitable intertwining of an artist’s colourful biography and aesthetic genius has provided fodder for scholarly speculation, populist fascination and plain, old-fashioned entertainment. Beyond the mere sensationalism, how important is persona in understanding an artist’s practice? It’s a question that has troubled art historians for a long time. For many, the artist’s persona is like the pesky shrew that is best chased away so as not to impede the historian’s or critic’s ‘serious’ quest for facts and objective interpretation.

Yet this antagonistic shrew has been an integral part of art history. Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, the sixteenth-century classic, and required reading for all students of art history, densely mixes detailed descriptions of the achievements of the great Renaissance artists (from Cimabue and Giotto to Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo) with biographical anecdotes intended to reveal their inner character and better illuminate their art. To say that Vasari was a good storyteller is like saying Frank Sinatra could carry a tune. He was, as one critic put it, a ‘profoundly inventive fabulist’ who not only embellished tales about dead artists, but also incorporated the self-propagated myths told to him by his contemporaries. His collection of biographies freely blended aesthetic theory, sociological description, fact and fiction. Five hundred years after Vasari’s death, art history has become a much more stringent practice. By dismissing Vasari’s factual errors and exaggerations, the current academic consensus continues to discredit one of his main contributions to the field – the idea that legend and myth, as generated by the artists themselves, are inseparable from understanding their art.

It is not only art historians who are to blame. Artists have always been granted a different status from the rest of the populace, and were, consequently, treated differently. They could speak to the gods. They were given privileged positions, disregarding traditional class divisions. As an inverted barometer for societal values, artists could safely act out fantasies, break the taboos and enjoy the indulgences that are shunned by the moral consensus. The figure of the artist possessed a unique duality, eliciting equal doses of fascination and contempt, envy and disdain.

The invention of bohemianism in nineteenth-century France provided an efficient means to prevent artists from contaminating everyone else. Derived from the name of a region in the Czech Republic inhabited by nomadic gypsies, the modern notion of bohemia designated a place where artists and disillusioned members of the bourgeoisie could intermingle with the poverty stricken, foreigners, racial minorities, homosexuals and anyone else on the margins of society. As the historical epicentre of la vie de bohème, mid-nineteenth-century Montmartre provided the populist view of how artists should live, behave and look. From the young struggling artist in an unheated Williamsburg loft to the DJ-cum-painter spinning in an electroclash club in former East Berlin, bohemian imagery persists in shaping contemporary expectations of what role artists should play in society.

However, not all artists continue to take refuge in bohemian or countercultural ideals. Western society has changed this, epitomised by the obsession with celebrity. The result has been that avant-garde strategies have been absorbed into mainstream culture, sucked in by the allure of the culture industry. So, what is left at the artist’s disposal? How, then, can they resist the culture industry? Should they resist? Are they passive victims or active proponents of this industry? What position should they occupy in this kind of society?

Many artists have consciously cultivated their public persona as a strategic, often antagonistic element in their art practice. While there is no single moment of origin when artists began to elevate their own personas into something more significant than simple biographical interest, there are those who have contributed to the transformation of persona into an autonomous field of artistic activity, equal to any traditional artistic practice.

This use of persona, however, should not be confused with a type of art practice that emerged in the course of the 1970s in which artists used their own life as their primary subject matter. Such figures as Sophie Calle, Christian Boltanski, Hannah Wilke, or Eleanor Antin utilised art as a sociological vehicle for the documentation of their everyday life.

Unlike these life artists, those under discussion here are uninterested in the documentary or narrative framing of their lives, nor are they committed to the veracity of the tales they use in their works. Instead, they harness Western culture’s attraction to and repulsion from the cult of personality in order to intensify the confrontational power of their self-generated myths.

Francis Picabia: Sea, Sex and Sun

Dadaist conspirator, enfant terrible of the Surrealist revolution, friend and occasional collaborator of André Breton, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray and Tristan Tzara, the French artist Francis Picabia (1879–1953) has an indisputable place within the pantheon of the historical avant-garde. As well as his important contributions to some of the major art movements of the twentieth century, Picabia had a ferociously unconventional persona. Echoing his fierce aesthetic independence, he did not conform to the image or lifestyle of his avant-garde colleagues. Born to a cosmopolitan family, the son of a Cuban diplomat in Paris, he never dabbled in bohemianism. He was rich and had no qualms about flaunting his wealth in public. More playboy than serious artist, Picabia and his wife Olga lived on a yacht in Cannes during the 1930s. While many of his contemporaries split their time between the Côte d’Azur and Paris, Picabia steered clear of artistic circles when socialising on the Riviera or in the capital. His relentless pursuit of pleasure was not only publicly acknowledged, but it surfaced in his work, as well as in that of other artists. His love of fast cars – Man Ray made several images of him with cars in the 1920s – was surpassed only by his insatiable taste for women. A self-portrait from 1940 depicting him with windswept hair and framed by two female temptresses is the artist as an unapologetic womaniser (he often made aphoristic analogies between the pursuit of art and the love of women).

Picabia’s male bravado and unabashed decadence takes on a more complex tone when read in parallel with his writings, letters, poems and aphorisms. A devout Nietzschean since early adulthood, he firmly believed that self-generated myth was one of the essential elements in his nihilistic programme. His carefully groomed public persona was, therefore, a part of his artistic strategy. As Carole Boulbes, a Picabia specialist, has written: ‘

Like Friedrich Nietzsche, Picabia interwove his writings with numerous aphorisms about art, love, the family, glory and money… When Picabia opts for scepticism and insists that there is nothing to understand, or when he prefers the critique of values to superfluous commentary on the works, this is in fact the expression of a philosophy. Throughout his literary and visual works he calls into question the founding oppositions of Western aesthetic categories (beautiful/ugly, pure/impure, good/evil).

Interpretations of Picabia’s art, writings and lifestyle are all subject to these Nietzschean principles of deformation and nihilism. When he strays from the orthodoxy of the avant-garde or cultivates a nonconformist, decadent persona, his acknowledged affiliation with Nietzsche makes it hard to judge his intentions at only face value. In this light, the superficial appearance of his sea, sex and sun lifestyle on the Côte d’Azur in the early 1940s seems deliberately challenging, particularly during a time of war.

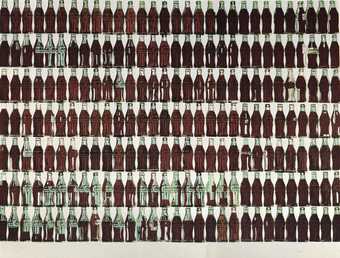

Andy Warhol: The wrong person for the right part

Andy Warhol wasn’t merely famous – he changed the nature of fame, and this impact was not limited to the world of art and artists. Warhol (1928–1987) founded his art practice on the careful choreography of his public persona. He harnessed the power of celebrity – his own, the celebrities he created, the culture’s growing thirst for celebrity as such – elevating it to a different status. For Warhol, his persona was an artistic medium, no different from the more conventional forms (film, painting, sculpture, photography) he used in his art.

Despite the ease with which we merge the figure of Warhol with today’s entertainment-obsessed society, there is little interpretation of the relationship between his construction of his persona and its direct impact on his art. The campaign to isolate and dismiss the importance of Warhol’s persona in terms of his overall artistic contribution is much more systematic in recent academic writing. Scholarly publications such as October attempt to sort out the persona problem by historicising Warhol into two distinct periods: the Early Factory Years (1960–8) and the Business Art Years (1969–87). Art historian and film theorist Annette Michelson has chosen the term ‘prelapsarian’ to characterise the first period. This biblical allusion perfectly sums up the notion of an evil that caused Warhol’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden. ‘After 1968,’ she writes, ‘Warhol assumed the role of grand couturier, whose signature sells or licenses perfumes… Warhol’s ‘Business art’ found its apogee in the creation of a label that could be affixed.’ While the pre-1968 Factory certainly flirted with celebrity and the mainstream vehicles of fame, it did so under critical auspices. For Michelson, the prelapsarian Warhol reflected the ills of mainstream culture through irony-soaked parody.

The shots fired from Valerie Solanas’s gun in 1968 signalled the beginning of his decline. It is a commonly held truth that this traumatic event soured Warhol, driving him toward more cynical modes of art making. This event also marked a dramatic shift in the way he consciously used his celebrity, and perhaps the emergence of public persona as a legitimate and autonomous artistic medium.

At least on the surface, Warhol’s life and art in the Factory carried on as before: he continued to make films, paintings and sculptures, as well as having a hand in various cultural enterprises. Yet as the delegation of his artistic production slightly increased, Warhol made even more time for public appearances. During the 1970s and 1980s, he continued to travel around the world, documenting his globetrotting through his Time Capsules. In New York, his social life epitomised the fashion of the time, and peaked with the decadence of such mythical clubs as Studio 54. Warhol behaved like any other star. His overactive social life was relentlessly photographed by the paparazzi, and he appeared regularly in the society and gossip pages, with Michael Jackson, Bianca Jagger, Joan Collins, as well as countless other stars, royals and society women. The list of Warhol’s companions on film was not only a barometer for who was hot in the 1970s and 1980s, but also reflected his Rolodex of celebrity clients for his booming portrait business.

Working for the Zoli modelling agency (available for “special bookings only”), Warhol sold his celebrity to various companies for product endorsements in television and print, giving a sense of inevitability to his early Pop appropriations of such banal products as Brillo scrubbing pads and Campbell’s soup. Whether he was modelling Levi’s blue jeans, advertising tdk videotapes, l.a.Eyeworks, or the ill-fated Drexel Burnham Lambert junk bond trading firm, or guest-starring on an episode of The Love Boat, these vulgar commercial activities were part of the logical culmination of Warhol’s trajectory. “Business art is the step that comes after Art. I started as a commercial artist, and I want to finish as a business artist. After I did the thing called ‘art’ or whatever it’s called, I wanted to be an art businessman or a Business Artist.”

Warhol refused to differentiate between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ appearances in this Business Art phase of his life. What counted was translating his persona into its most extreme commercial potential. Yet while he was trying to maximise the impact of his public persona in the spheres of art, popular culture and the market, he insisted on highlighting his imperfections, his personal neuroses and his claim to be ‘Nothingness Himself’. This paradoxical coupling of extreme public exposure and sense of invisibility might be chalked up to some manifestation of false modesty, as morally bankrupt as his indiscriminate activities, but it could also be attributed to the fulfilment of one of his philosophic maxims. When he describes himself as ‘putting his Warhol on’, he enumerates what he sees in the mirror:

Nothing is missing. It’s all there. The affectless gaze. The diffracted grace… The bored languor, the wasted pallor… the chic freakiness, the basically passive astonishment… The glamour rooted in despair, the self-admiring carelessness, the perfected otherness, the shadowy, voyeuristic, vaguely sinister aura… Nothing is missing. I’m everything my scrapbook says I am.

Warhol worked very hard at being the wrong person for the right part. His ‘wrongness’ was documented in his obsessive archival activities: the publication of his Diary and The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again); his scrapbooks and Time Capsules. More than any ‘artwork’ or film he ever made, Warhol’s public persona became the most effective device to record and reflect on contemporary life. If the role of the artist today is to search for ‘aura’ in a world of vacuity, Warhol was definitely the wrong person for the right part.

Jeff Koons: The new Adam

Jeff Koons (born 1955) is one of the unmistakable icons of the 1980s – as much through his affiliation with the ‘commodity art’ scene that emerged out of New York’s East Village as through his continuation of Warhol’s legacy. Koons consciously took up where Warhol’s Business Art left off by espousing mass media and the market as the subject of his work while harnessing their strategies in the promotion of himself.

In every interview that Koons gives about the content of his work, he infuses his otherwise ‘empty’, ‘vulgar’, ‘icy’ and ‘banal’ œuvre with more than just biographical details. His discourse is peppered with pseudo-revolutionary maxims, explaining the desires that drive his art: ‘to communicate with the masses’; to provide ‘spiritual experience’ through ‘manipulation and seduction’; to strive for higher states of being promised by ‘the realms of the objective and the new’. His professed love for the media goes beyond its usefulness as a communication tool: ‘I believe in advertisement and the media completely. My art and my personal life are based on it.’

During the 1988–9 art season, Koons and his galleries put their money where their mouths were. A series of full-page advertisements was purchased in the major trade magazines of the time – Artforum, Flash Art, Arts and Art in America. In the centre of each highly theatrical tableau, Koons presided over the scene, smiling smugly at the camera, impeccably groomed, obviously airbrushed. Each of the four ads illustrated one of the derogatory aspects of his persona as propagated by the press: Koons as a ‘breeder of banality’ (pictured with two pigs); Koons as ‘corrupter of the future generation’ (photographed in a schoolroom full of children with slogans such as ‘Exploit the Masses’ and ‘Banality as Savior’ written on the blackboard behind him); Koons as gigolo (pictured in a Hugh Hefner-style robe in front of a boudoir-like tent); and Koons as frivolous ladies’ man (posing with bikini-clad models and a braying pony). These self-satisfied images marked the introduction of Koons’s own image into his work, while beating the critics to the punch. He called himself a pig, an indoctrinator, a whore and a narcissist before the guardians of ‘truth’ and ‘authenticity’ could even attack his next body of work – Made in Heaven.

By now, everyone knows the story. Koons met the Eurotrash pop singer/porn star/member of the Italian parliament Ilona Staller (aka Cicciolina) in 1989 after having based the sculpture Fait d’Hiver (from the Banality series, 1988) on a found image of her body. Having initially solicited her involvement in Made in Heaven, their collaboration fast turned into a real-life love affair and marriage. The resulting works – an ensemble of life-size sculptures in wood and plastic, paintings, glass figurines and a billboard advertising their unrealised porn film – graphically depicted acts of matrimonial consummation. Moral backlash aside, this union of art and life pushed the perception of Koons over the edge – even in the art world. In the end, sexual exploitation was a minor irritant in this story. The real taboo that Koons shattered can be located in the manner in which he used his very public relationship with Staller to challenge the humanistic expectations of the role of the artist in contemporary society. As Sylvère Lotringer writes:

[Koons] embraced the System as publicly as he kissed Cicciolina’s ass. Ilona Staller became his best PR, using her genitalia, Koons said, to ‘communicate a very precise language’. He never had to deny or ‘deconstruct’ anything to make his point. The culture industry was doing it for him.

With this foray into sexploitation, Koons’s proclamations about Ilona and himself are most radical when taken at face value. As the ‘contemporary Adam and Eve’ (as Koons put it), they were far from taking the position of passive victims of capitalism’s malicious impact on society and art. Twisting the biblical reference to fit contemporary life, the Koons-Staller union embraced the supposed ‘sins’ of the market, brazenly shattering the expectation that artists should operate in a higher moral realm; it removed the money, power and celebrity that corrupts the rest of society. With this complicity, Koons fulfilled his role as the new Adam, blissfully savouring the once-forbidden fruit offered by the American way of life, minus the cynicism or guilt that plagued his artistic forbears.

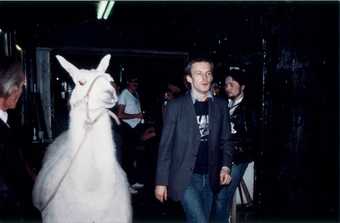

‘Every artist is a person’: Kippenberger as Selbstdarsteller

Martin Kippenberger (1953–1997) didn’t need to die prematurely at the age of 43 to become a cult figure in Europe. At the end of the 1970s, before deciding to become a visual artist, Kippenberger’s main preoccupation was self-invention. He went to Florence in 1976 ‘looking like Helmut Berger on a good day’, but was never discovered. He returned from Italy and temporarily moved to Paris to become a novelist (he never finished his novel, but continued writing throughout his life). In 1978, he established the Büro Kippenberger in Berlin with Gisela Capitain. This marked his formal debut as a visual artist, although his office was more than a studio, as it blended all forms of artistic endeavour à la Warhol’s Factory. Shortly thereafter, Kippenberger became co-owner and manager of s.o. 36 in Kreuzberg, the centre of the punk and new wave scene. To mark his 25th birthday that same year, he printed a poster picturing himself with a hooker, with the banner title, ‘A Quarter of a Century as one of you, among you, with you’. The epithets chosen by himself – ‘show-off’, ‘hypervoyeur’, ‘pretender’, ‘informer’, ‘organiser,’ ‘ringleader’ and ‘big spender’ – surrounded his head like a halo. During this early yet hyperactive phase in his life, his indecision about his vocation produced a maelstrom of creative activities. The only thing that was constant was his tireless, systematic promotion of his persona.

Kippenberger’s invention of Kippenberger was not limited to his early career; it was an ongoing process. His nicknames and alter egos appeared everywhere he worked: Kippy, Der Kippenberger, MK, Spiderman, a crucified Frog, or just plain Martin. He wore as many hats as he had names for himself: painter, sculptor, architect, writer, poet, underground club manager, musician, promoter, exhibition maker and director of his own museum (momas, the Museum of Modern Art Syros). It was impossible to disentangle his self-promotion from his way of life.

The German language offers a perfectly tailored word to designate Kippenberger’s programmatic drive. Selbstdarsteller, as Diedrich Diederichsen writes, is ‘often translated as ‘self-publicist’ or ‘self-promoter’, but literally means ‘self-performer’ ‘. In his text on Kippenberger’s art and life between 1977 and 1983, Diederichsen goes on to explain that in contemporary German parlance, the term Selbstdarsteller is usually used as an epithet in the realm of politics, while in the arts takes on a more ambivalent tone. Kippenberger as Selbstdarsteller can be compared with equally self-promoting/self-performing artists, ‘poised somewhere between Serge Gainsbourg and Klaus Kinski’. Yet the nuance offered by the German term – its oscillation between promotion/publicity and performance of the self – raises an important distinction. Unlike the purely cynical marketing strategies in the mainstream of the music business and the art world, Kippenberger’s Selbstdarstellung contained a complex economy of checks and balances, promotion and self-effacement, exuberance and humility, gut-splitting humour and profound melancholia.

‘Every artist is a person,’ Kippenberger said. Originally a critique of Joseph Beuys’s maxim, ‘Everyone – each person – is an artist… The Revolution is in us’, Kippenberger’s humble statement might seem to contradict his own self-generated mythology. His first artwork – a cycle of 100 small-format paintings titled One of You, A German in Florence, made out of frustration with his acting career in 1977 – might hold the key to this seeming contradiction. One of You, A German in Florence offers a panoply of snippets from Kippenberger’s everyday life in the modern Renaissance city, rendered in black and white oil paint. This multipanelled work – deliberately reminiscent of Gerhard Richter’s grisaille 48 Portraits of Important Men – is Kippenberger’s first attempt to create an open system of images, signs, language, high and low cultural references and architectural motifs. From the depictions of a typical hole-in-the-ground toilet to a neon sign of a local ice-cream parlour, from a portrait of an Italian crooner to a neighbourhood milk man and a copy of Sandro Botticelli’s Portrait of a Young Man with a Medallion 1470–5, this is more than a picture of the human condition. Kippenberger always counted himself among us.

As one critic noted: ‘Kippenberger staged his public life because he thought he could bear it better in its mythologised form. He demythologised art and the conditions of its creation so that it would not lose its credibility.’ Kippenberger’s contradictory yet poignant use of self-performance/self-promotion was one possible answer to the challenge of existing in the contemporary cultural landscape.