William Blake

The Ghost of a Flea

(c.1819–20)

Tate

Michael Bracewell

Do you remember when you first visited Tate?

Damien Hirst

I hitched down from Leeds with my mates, either Hugh Allan or Marcus Harvey. They were a bit older than me, and we had been friends from when I was about twelve or thirteen. It must have been the late 1970s, early 1980s. We would do a weekend in London, as well as go in the school holidays. We did loads of museum visits – the National Gallery, Tate, as well as galleries on Cork Street. At that time I probably wasn’t that into contemporary art, so it was just looking at any art really.

Michael Bracewell

One of the works you saw at Tate that made a particular impact was William Blake’s The Ghost of a Flea c.1819–20, which is an amazing thing. What is it about this image that appeals to you?

Damien Hirst

I think firstly it’s the scale. I always wanted to do big things when I was younger. I thought big is good. But when I saw the Rembrandt etchings, I remember having a conversation with Marcus about them and him saying: ‘Well, you know, you’ve got to look at it more, because scale is different from size. This has got enormous scale, but it’s very, very small.’ I couldn’t work that out. So when I came across the Blake painting, I thought: ‘What is it? It takes you in there. It’s dark, and it’s scary, and it has this huge scale.’ Then you think: ‘Where is the flea? What is the flea? Why is it the ghost of a flea?’ It was probably the most frightening image I’d ever seen. It seduces you; it asks so many questions, but doesn’t answer them. I really enjoyed thinking about it and looking at it. I went back and saw it a few times. Later, I looked at all Blake’s work, but it didn’t have the same power as that image. It has that David Lynch feel to it, hasn’t it?

Michael Bracewell

Your own work seems always to maintain this strong sense of mystery, however immediate the image or choice of media.

Damien Hirst

Yes. As an artist you discover something, but I don’t really think you invent anything.

Michael Bracewell

Did the idea of an artist who was a visionary outsider interest you?

Damien Hirst

I don’t know… I liked all artists, and I was just devouring it all. I accepted that artists were like Joseph Beuys, so Blake seemed to be somebody who just took it all on board, who covered a lot of ground. That’s what an artist was.

Michael Bracewell

Do you think that artists such as Beuys, Blake, or indeed Marcel Duchamp, are to some extent the nearest we’ve got to visionaries, or seers, or magicians?

Damien Hirst

Art is important on that level. We need art. It gets closer to the religious, so I don’t know if you need to put it into words. Art is magical, there’s no denying it, but it can’t cure cancer. It’s just an aid, really, something to help you.

John Martin

The Great Day of His Wrath

(1851–3)

Tate

Michael Bracewell

I wondered whether John Martin’s The Great Day of His Wrath 1851–3 might appeal to you. He made these epic paintings that often described the end of the world, or the life to come.

Damien Hirst

Yeah, I love that. I was at a Roman Catholic school, where to begin with I was taught by nuns. I’d go straight to the Crucifixion section of the illustrated Bible because I loved all that imagery – the blood coming down the feet and the hands. I was definitely indoctrinated as a child. I spent a lot of time in church, but I was bored out my mind. I stopped going when I was twelve. At school we had the religious books we had to read from… I’m sure that’s all affected me, but I do think it’s a crock of shit. With Father Christmas, you get to eight or nine years old and start to see holes in it after you catch your parents in the bedroom bringing your presents. Whereas with religion, the grown-ups don’t tell you it’s all made up, so your mind is forming these questions as they’re telling you these silly ideas – that Eden is a place on earth, and if only mankind could find it, he’d be happy. And you’re thinking, well, it must be near the Nile somewhere, or up the Amazon. Because, as a kid, you want answers, don’t you?

Michael Bracewell

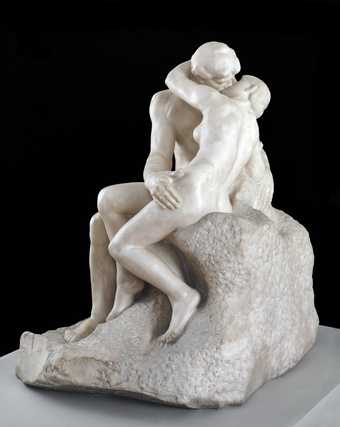

Perhaps there is a connection with the idea of scale that you mentioned? How an artwork can be monumental, but in different ways, as with a sculpture by Rodin, for example?

Auguste Rodin

The Kiss

(1901–4)

Tate

Damien Hirst

Yeah, I like Rodin. I remember seeing The Kiss 1901–4 at Tate. Early on, I used to do a lot of life drawing and stuff. I looked at books on Rodin because I thought I should understand anatomy, and I realised that in this day and age you don’t need to learn that. Before then, I would be drawing a naked woman in front of me and trying to draw her actual hip or thigh bone, instead of her. Rodin really helped me to look at the world.

Michael Bracewell

Was there a work for you that seemed to unlock your understanding of art? Or is it a constant process of unlocking?

Damien Hirst

There are things I’ve made that I look back on that are important now, but which I felt were horrible at the time.

Michael Bracewell

Such as?

Damien Hirst

In 1981 I did a drawing of Delacroix’s Orphan Girl at the Cemetery 1824. I just gridded it up and tried to copy it. I think I managed to capture what was in that image in mine. I discovered something by doing that.

Michael Bracewell

Do some people assume you simply put a shark in a tank, and from that point on you were a famous artist?

Damien Hirst

People have always been suspicious of modern or contemporary art, I guess. When I was at college I remember throwing paint around in an art class when the teacher wasn’t there, and just saying: ‘What’s that? It’s modern art.’ And everyone laughed. I think everybody laughs at ‘modern art’ because the media laughs at modern art. But the artist has to have a background of some sort of logic, or some understanding. You have to know what you’re doing, it’s just to what extent. We’re definitely not trained. Anyone can draw perfectly – you just need to be taught. But how relevant is it to have those tools in the world today? I suppose every generation does that, don’t they? You look back and you just think: ‘When I was a lad it weren’t like that.’

Michael Bracewell

David Bomberg’s Ju-Jitsu c.1913 still seems so aggressively modern. Is that why you would include it in your list of works at Tate that are important to you?

Damien Hirst

I like Bomberg because he went from landscape painting into abstraction in a really good way, by hanging on to the figurative within the abstraction. I could understand that. It’s from the old into the new world. He’s a very accomplished painter, and if you look at his later figurative paintings of Israel and Jerusalem, they’re great, even if they are very formal. I always think that any good artist’s career is like the map of a person’s life, and Bomberg is perfect. With Edward Burra, for instance, you don’t really notice a lot of change. In works such as Bomberg’s Bathing Scene c.1912–13 or Ju-Jitsu, you think, why is it getting simplified? I remember for years looking at Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon 1907. I knew it was an important painting, but I couldn’t work out why it was important. With Bomberg, I saw his personal journey in trying to reduce things to abstraction, which seemed so genuine. There’s a lot of exploration throughout his career, and that’s what excited me about his work. His early and late paintings seem as if they’re by two different people. I always like that in an artist, because I do that a lot myself – trying to escape who I am.

Michael Bracewell

Do you ever feel that you’re trying to escape the back catalogue of your own visual language, whether it’s the formaldehyde or cabinet pieces, or your work with butterflies?

Damien Hirst

I think very early on I tried not to make a Damien Hirst, which is stupid. Now I just accept it. I suppose one thing I do try to avoid is being trapped in your own idea of yourself. I don’t want to be like, say, Arman, remembered only for his ‘accumulation’ boxes.

Michael Bracewell

Was Picasso trapped in his idea of himself, or do you think he managed to escape from that? If you take two examples of his work, one from 1914 and one from the early 1970s…

Damien Hirst

He covers so much ground. A lot of ideas that any art student has, Picasso had them already. He took a huge amount of what was possible, and took it for himself. That is his power. He was brilliant at that balance between the two-dimensional and the three-dimensional, the illusion of space and real space – and all using real life as a departure point. But, you know, he never left the picture plane, which is brilliant. He made it the whole world, which is difficult to do. Picassos are infinitely awesome, aren’t they?

Michael Bracewell

I recently went to look at the collection of Picassos in Berlin, and you notice how towards the end he seems as if he’s almost beginning to send himself up: playing at being Picasso.

Damien Hirst

A bit like a child. I mean, children do it really easily.

Michael Bracewell

In some of those films of late Elvis, he’s obviously just spoofing his own myth. He’s being the first Elvis impersonator, in some ways.

Damien Hirst

I think that whatever you do as an artist, you have to be honest. Even if you’re saying I don’t know what I’m doing, you just have to say it.

Michael Bracewell

I believe, although I might be being too romantic, that artists have to be truthful. That the moment an artist lies or becomes emotionally dishonest, their work fails.

Damien Hirst

I don’t think it’s that simple. Artists deal in truth, and lies are part of life, so you can definitely lie. Jeff Koons plays with deception in some of his self-portraits, because he’s not really who he says he is, but he’s honest about saying: ‘I’m not who I say I am.’ So it’s truth, but not the truth, and it’s not lying. You never get 100 per cent of the truth. You have to be attempting to produce the truth, and lies are involved in it in a huge way. The material you’re dealing with is truth, and it can’t be lies, but you can use anything available to you to get there. Warhol was always hiding part of himself, because he wore a wig; he was shy, and he was nervous. He was not showing you himself. I don’t think artists ever show themselves. They show you something else.

Michael Bracewell

Does their art show you themselves?

Damien Hirst

It shows you yourself, and I think they put in a hell of a lot of themselves in order to make it show you yourself, more than is humanly possible sometimes. If an artist showed you himself and his truth, it would bore your tits off. As an artist, you’re definitely not selling people shit they don’t need. You can leave that for the advertisers. You are selling people things inside themselves that they’ve forgotten they have.

Michael Bracewell

Bridget Riley quotes an essay that Samuel Beckett wrote on Marcel Proust, where Proust says an artist is a person who has ‘an inner text that they need to translate’. In other words, they have something inside of them that they need to translate out of the personal and into the universal. So they are not telling you anything about themselves, but they are managing, through the art, to show their feeling and their vision to the world.

Damien Hirst

Yeah, I agree with that. That’s a good way of looking at it. I always think the truth is important within reason. It’s not a goal. But you’ve got to believe 100 per cent in what you’re doing. If you don’t believe, nobody else will.

Michael Bracewell

Duchamp said that art must always have an element of hilarity about it. Is that something you would recognise?

Damien Hirst

I don’t know if hilarity is the right word. It does have that, because, for me, hilarity can be horror; because horror makes you feel small and stupid and pointless, but not without hope. You could say it’s hilarious, but slipping on a banana skin is hilarious, and if an old woman breaks her hip, it’s not that funny. So no one has to get hurt, for it to be hilarity. But I definitely think art is about getting into the mind; making people forget the drudgery of everyday life. You want to remove that and put in something more fundamental or awe-inspiring.

Michael Bracewell

A blurred line between comedy and sadism, or pathos and violence – a kind of aggressive abjection – seems key to some of Bruce Nauman’s work, which I know you admire. One example that Tate has is the video piece Violent Incident 1986.

Bruce Nauman

Violent Incident

(1986)

Tate

Damien Hirst

Yes. You see a couple having dinner, helping each other to the food, but they end up beating each other up. She pulls the chair out for him to sit down, and then pulls it away, so he falls on the floor. I think she ends up knifing him, or him stabbing her, so the kitchen utensils turn into weapons. It’s on twelve monitors, all showing at different times. On one of screens the meal is beginning, and it’s pleasant, and on another it’s turning nasty, and then on another it’s totally brutal. It goes on continuously. It is like human relationships – you start one, and then you fuck it up. I think it’s what life is like. We are constantly attempting the impossible in human relationships. We’re trying to be together when we’re separate. We’re separated by flesh and bone, and we’re trying to fuse that together. We’re trying to live forever when we know we’re going to die. We’re trying to be nice to people when they can be nasty. We’re trying to control things that are uncontrollable. This is the drama of life, and that’s what’s exciting about it. To shine a light or hold up a mirror to it, or to throw it back to people and say: ‘The things you are looking for are right in front of your nose… this is it. There is no next week; this is it now, you know.’ That’s what I love about art. It does that. There is a quotation by Sir Joshua Reynolds above the door of the Victoria and Albert Museum that says: ‘The excellence of every art must consist in the complete accomplishment of its purpose.’ It is a statement that is a conundrum, and, to me, a bit like Nauman’s neon sign The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths 1967. You ask yourself, well, where’s the answer? There is no answer! But that is the answer. So where’s the mystic truth? That’s the mystic truth revealed, absolutely revealed. And it’s constantly being revealed. The more you reveal it, the more it hides or escapes. And that’s why we split up, and that’s why we get back together.

Michael Bracewell

This idea of a tipping point within the instincts that can control our feelings seems key to much of your own work: the point at which a riddle or a conundrum becomes a trap.

Damien Hirst

There’s a great book called Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence by Esther Perel, which is about why relationships are difficult. It says that the human child has an overwhelming urge to run away from its mother and explore the world, but an equally opposing desire to stick as close to its mother as possible. That’s what it is to be a human being. In 2007 I made a sculpture titled after it, which is very similar to the Nauman one, called Love’s Paradox (Surrender or Autonomy, Separateness as a Precondition for Connection). It is about the balance between the two things, surrender and autonomy. Like, you’ve got to be independent. What’s sexy is somebody who is independent, but in a relationship, you’ve got to give up that independence. Once you do, it’s not sexy. So you’re not attracted to the thing that makes relationships work. You want what you can’t have.

Michael Bracewell

I met Quentin Crisp in New York, and he told me why he’d lived alone all his life, as a kind of philosophical outsider. He said it was nothing to do with being gay; it was because the moment somebody gave him what he wanted, he would no longer want it. And speaking of gay outsiders, I know you’re a huge admirer of Bacon. I think I know the answer already, but what is it about his work that makes you feel so strongly?

Damien Hirst

I remember early on looking at some images that Georges Bataille collected of Chinese executions, of people being tortured and cut into pieces. The power of an image such as that just blows your mind. When I was a kid I would always stop at a dead cat in the street. I was a bit morbid, I guess. But an image can be anything and can come from anywhere, and you can use anything available to create that image – and Bacon created unforgettable images that you can’t get out of your head. I guess he liked the struggle too. Like Picasso, he’s very upfront about not trying to trick you. The questions come endlessly, but there are no answers. The whole thing in itself is an answer. You understand it, and you believe in it. But then you don’t see. Life is here to think about, to enjoy, or to discover, isn’t it? Bacon paintings always raise those questions for me.

Michael Bracewell

Is immediacy in art very important to you?

Damien Hirst

Yeah, it’s got to do its thing first of all. It has to get hold of you. You’ve got to look at it and go, ‘Wow’. The first time I saw The Ghost of a Flea, I can still remember it being spooky, and the hairs on my neck standing up.

Michael Bracewell

I believe it’s something that you do, by putting together two things that one would never think of putting together, and they create this new third thing that grabs the viewer immediately.

Damien Hirst

I think art is one plus one equals three. But it’s a third thing and a fourth thing and a fifth thing – things start to happen. You can’t look at that curtain in the Bacon painting Study for a Portrait 1952, for example, and answer the question of it without seeing everything else. So that’s what the problem is. And once you do that, you can’t look at the face of the guy without looking at the box. You don’t doubt that you know why he’s screaming, but what is he screaming about?

Michael Bracewell

Duchamp is often regarded as either the saviour of art or its antichrist. Do you think people have said the same about you?

Damien Hirst

When I was at college the neo-geo-artist Jeff Koons was either saviour or antichrist. That’s what appealed to me. And it was what the Sex Pistols were to me in music. With my work, I’ve never really thought about it, I just tried to ignore it. My battle has always been with the media. I thought, this is a fight I’ve got to win. They’re going to take what I make, they’re going to reduce it from whatever size it is to a small black-and-white photograph, and they’re going to ridicule it. So everything I made had to be able to survive that. I couldn’t be too honest about my feelings, because that’s probably what my early work was like. So then you start thinking, how can I do some things that are stronger than that, where I still get my feelings in, but they’re not out there to be brutalised? I really enjoyed that early on. I remember thinking there were going to be cartoons about this. When we were doing Freeze, we knew we weren’t going to wait for an audience, or wait to be discovered, we wanted to go out and get the audience. Art was already getting slagged off in the tabloid newspapers, from David Mach to Carl Andre, but slagged off by people who were not actually visually educated. They just thought that society as a whole was stupid, so would say: ‘Here, look at this shit.” There was a reporter standing in front of my fish piece with a bag of chips. I loved that. I thought, this is how it’s got to survive… you know, it’s got to look good. I don’t care if there’s a guy standing in front of me with a bag of chips, he’s still going to ask: ‘What the fuck is that?’

Michael Bracewell

You were friends with Richard Hamilton, and I know you really admire his work. What specifically do you respond to?

Damien Hirst

I was aware of Richard first of all from doing The White Album, which I thought was phenomenally brave after Peter Blake had done Sgt. Pepper’s. I imagined he had done it to sort of say ‘fuck off’ to The Beatles, because they were the artists when he should have been the artist, and they were getting mass cultural appeal. But, on the other hand, they gave him carte blanche to do what he wanted. And to come up with that idea… You know, he just seems to have art that had power.

Michael Bracewell

Do you feel, with your own work, that all of the artists we have discussed, from Blake to Nauman and Hamilton, are feeding into your ideas, and that, to some extent, you are carrying on their thinking to another stage?

Damien Hirst

Yeah. It’s that John Ruskin idea that art is a relay race which goes back to the cave men. I think that’s what it is. I believe all art starts its life as contemporary, and every day that we wake up the world is different from the day it was before. Art is still around there to communicate to people who haven’t been born yet what that world is like. That’s what great artists I’ve looked at in the past have done, and that’s what I try to do. That’s what all artists try to do.