In 1997 Yukiko Ito, a curator in Hiroshima, invited me to take part in Hiroshima Art Document, an annual exhibition she had started as an atomic bomb memorial in the grounds of a large compound of four brick buildings that had survived the blast almost intact.

Originally a factory for making Japanese imperial army uniforms, it became an improvised emergency hospital on the day the bomb dropped. Today, it is a rare monument – abandoned buildings that will never be used again.

I was sent photographs of the compound so that I could start thinking of a site-specific work. Immediately, it caught my eye that the profusion of weeds growing around these buildings and yards had all pushed their way through the asphalt. There was no soil to be seen. Their resilience was so striking that I knew they would become my working material.

When I arrived in Hiroshima I found myself alone with these weeds and the incessant song of the cicadas in the unbearable heat of early August. I felt I had to talk to them, and, as one does with people, I wanted to address them by their names. I asked a botanist to identify them and he found 32 different species, some indigenous but many from America, brought by soldiers and goods. As if in a botanical garden, I installed a metal plaque next to each species, labelling them with their Latin, Japanese and English names. Next to each plaque I placed a thin bamboo pole from which hung at eye level a numbered piece of paper with the handwritten Japanese translation of what I had told them in English. The work was titled Addressing the Weeds in Hiroshima. Visitors walked around the buildings and yards reading from one weed to the next.

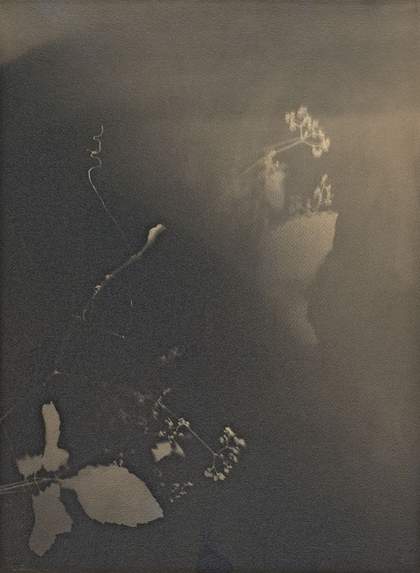

Mr Watanabe, the botanist, gave me an herbarium with all the weeds as a departing present, making it possible to work with them again. I remembered the historic photographs of shadow-images fixed on walls by the brightness of the explosion – photograms of a unique kind. This time I was alone with the weeds in a darkroom in Lisbon. Laying them on photographic paper on the other side of the world, almost a year after they were taken from their asphalt home, was something I did with a lump in my throat.