Rebecca Horn

Mechanical Bodyfan 1973–4

Photograph by Achim Thode

© Rebecca Horn 2016

We have an inherent desire to go beyond our capabilities, to push beyond our limits. We study to increase knowledge, make machines to produce more than we can with our own hands, create devices to go faster, see further, speak louder and, when our bodies refuse to do what we think they should, we find ways to supplement them and exceed our corporeal boundaries.

Technology is everywhere, and we swim through most of our current lives in an intangible digital realm. The body, though, is analogue and driven by the senses, and we have long built palpable extensions for it. Often the best way to understand something is to try to make it. What happens, then, if we try to make a body? Eighteenth-century automata were exactly that: mechanised beings with the appearance of life. As science historian Simon Schaffer explains, automata developed from clockwork mechanisms regulating time into entertainment, and then into machines synchronising labour for the industrial revolution. Jacques de Vaucanson was a pioneer of automata. He studied human anatomy to work out how to construct a living being, and in doing so discovered our automatic functions – lungs, for example, work like bellows. In 1737 he created a flautist that could play for more hours than any human, and in 1745 invented the first fully automated loom that would eventually radicalise the capabilities of production.

Vaucanson’s inventions became the basis for the collection of automata at the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris, and it was here Marcel Duchamp encountered them, displayed among clocks and mechanisms. His fascination was fuelled too by literature, including Raymond Roussel’s surreal travelogue Impressions of Africa 1910, where machines replace humans and humans make use of mechanised organs, and Auguste Villiers de L’Isle-Adam’s The Future Eve 1886, where a fictionalised Thomas Edison creates a replica of a friend’s fiancée that is ‘an Android of my own making… with all the illusion of life’. In Duchamp’s masterwork The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) 1915–23 he describes the Bride, in his notes to accompany the piece in the publication The Green Box 1934, as a ‘new human being, half robot and half fourth dimensional’. The Future Eve would popularise the term android, while robot entered the language through Karel Capek’s play Rossum’s Universal Robots 1920 – robot being the English translation of the Czech robotnik, meaning forced labour or drudgery.

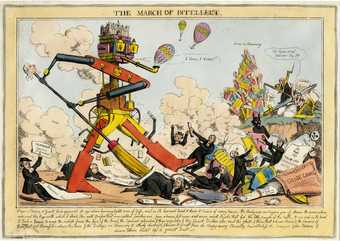

Robert Seymour

The March of Intellect c1828–30

Handcoloured etching on paper, 249mm x 350mm

The original caption reads: ‘Satire against corruption: a huge automaton representing the new London University (later University College London) tramples over greedy clerics, doctors, lawyers and the crown’

© Trustees of the British Museum, courtesy The British Library

The simultaneous hope for technology and fear of its impact fills visual art – from Robert Seymour’s 1828 etching March of the Intellect, showing the steam engine as an autonomous mechanical monster exhaling hot air balloons, to Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis 1927, and even to the 2015 television series Humans. Seeing human beings mimic machines and machines mimic human beings is fascinating – especially for the failures, when technology reveals our limits and vice versa. Artworks have a crucial role in enabling us to imagine our own selves through the technologised body, particularly in times of crisis. Some demonstrate dark futures of body augmentation – for example Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill 1913. In 1940, he described this plaster figure supported by the eponymous drill as: ‘The armed sinister figure of today and tomorrow. No humanity, only the terrible Frankenstein’s monster we have made ourselves into.’ The sculpture was first exhibited in 1915, but at its next outing in 1916, the year of the Battle of the Somme, the artist stripped away the drill, legs and one arm, casting the eviscerated figure in gun metal and re-titling it Torso in Metal.

Jacob Epstein

Torso in Metal from 'The Rock Drill' 1913-14

© The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein

Other artworks satirise humanity’s failings through the mechanised body: Hans Bellmer’s series of works La Poupée (The Doll) c1934–8 offered a critique to the stereotypes of physical normalcy propagated by Nazi art and culture, while Yael Bartana’s animation Degenerative Art Lives 2010 reworks Otto Dix’s 1920 painting War Cripples, showing amputee soldiers returning from the First World War in an endless march of automata. This was a technological conflict carried out through analogue means, and injuries suffered by surviving soldiers were shocking, leaving surgeons to reconstruct the body, while artists attempted to understand this new world through the fragmented figure. The industrial war saw human losses on a scale never seen before and the mutilated body was brought into public life.

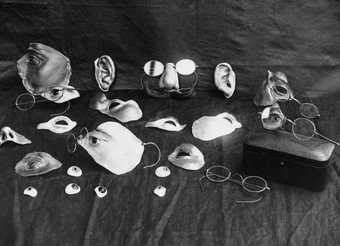

The sculptor, physician and physical therapist Robert Tait McKenzie noted that the ‘calamity of war’ necessitated new ways of medically dealing with the body. The nature of trench warfare resulted in hitherto unseen facial injuries that left relatives horrified and made life near impossible for the soldier on returning home. The sculptor Francis Derwent Wood turned very practically to address this injury: in 1916, at the 3rd London General Hospital, he set up the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department, aiming ‘by means of the skill I possess as a sculptor to make a man’s face as near as possible to what it looked like before he was wounded’. Casts were made of the disfigured faces, then clays of plasticine squeezes, and from this a paper-thin galvanised copper mask, painted to match the subject’s face, held in place by a pair of glasses.

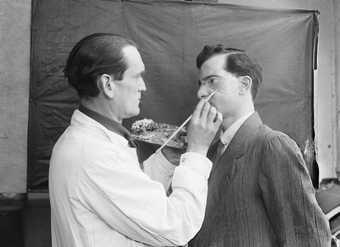

Captain Francis Derwent Wood RA of the Royal Army Medical Corps holds an artist’s palette as he adds the finishing touches to a patient’s new facial plate

Photo by Horace Nicholls, c1914–8

© IWM, courtesy the Imperial War Museum, London, originally from the Ministry of Information collection titled The Development of Reconstructive Plastic

Selection of items used to disguise facial injury during the First World War and early development of plastic surgery; the original caption reads: ‘Repairing war’s ravages: renovating facial injuries’, c1914–8

© IWM, courtesy the Imperial War Museum, London, originally from the Ministry of Information collection titled The Development of Reconstructive Plastic

As well as repairing, artists represented the technologised body as a symbol of the horrors of war and of creeping industrialisation that hastened as wartime technological advancement quickened production. In the wake of the First World War, the violence of modern life is explicitly seen in Torso in Metal, and in Heinrich Hoerle’s painting Monument to Unknown Prostheses 1930. Hoerle became involved in the Cologne dada art scene after a short period of military service. In 1920, the same year as Dix’s War Cripples, he published Cripples Portfolio, 12 lithographs drawing attention to, and calling for society to help, the war-wounded soldiers returning to the Weimar Republic. During the First World War the German population experienced casualties of more than 10 per cent, and the survivors’ fragmented bodies were as shocking as the deaths. Statistics show one in every 16 citizens encountered on the German street in 1919 would be a veteran who had suffered visible physical injury, and one of every 1,000 of these was an amputee.

Monument to Unknown Prostheses was produced a decade later. Two figures wear prosthetic arms reminiscent of ‘work-arms’ developed by the rehabilitation industry (there are chilling photographs of men using these while working in armament factories). Both have injuries to the head, pointing to psychological and physical damage, while a third sits with legs awaiting prostheses to be fitted. Unlike Cripples Portfolio, this does not ask for help: it depicts mechanised bodies reconfigured for industrial production. The heroes of this satiric monument are the prostheses, the human cost of war, and the new ready-for-production body.

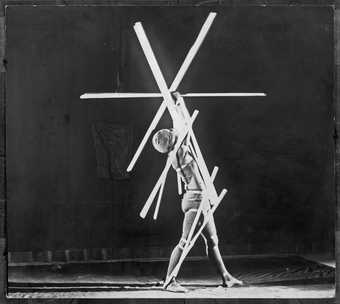

This attention to the prosthetic figure has ricocheted through 20th-century art, with artists expanding the body beyond its limits. Extensions celebrate possibilities while revealing the constraints we have engineered for ourselves. Working directly after the First World War, Oskar Schlemmer’s body supplements amplified the frailties of both the natural and enhanced body. He had experienced a short period of military service and, while in hospital recovering from injury, saw many men with lost limbs. The sculptural costumes of his Triadic Ballet, first performed in 1922, forced performers to submit to the weight and geometric form of their attire, while Slat Dance 1 from 1927 used equipment designed for physical education to lengthen the dancer’s limbs. Just as 18th and 19th-century ‘progress’ compelled people to conform movements to the rhythm of the factory, Schlemmer’s constricting additions forced their wearers to empathise with their own mechanics.

A dancer poses during Oskar Schlemmer’s Stick Dance, part of his Triadic Ballet 1926–9 (reproduced in 1980)

Courtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Some four decades later Rebecca Horn started making what she called ‘body sculptures’ – prostheses and masks extending and restricting the body. In 1968, while a student, she read Jean Genet’s semi-autobiographic novel The Thief’s Journal 1949, recounting his travels through 1930s Europe where he received an education in thievery mentored by the one-armed Stilitano, which became a key reference point for her. Horn’s Arm Extensions 1968 bandage the body and make the upper limbs scrape the floor, Pencil Mask 1972 enables drawing with the face, Scratching Both Walls at Once 1974–5 allows the arms to reach across a room. Like prostheses, her supplements are always for a specific person – and they fit into custom-made suitcases, not unlike those designed for medical equipment. Rather than aiding, though, her additions encumber movement, echoing Schlemmer’s choreography.

While Horn was conducting her experiments with prostheses, Feliza Bursztyn created failing, human-like machines. Her humming, squirming sculptures writhe with a restricted sexuality, at once human and inhuman. Beds 1974 consists of 13 beds covered with satin sheets, underneath which motors rumble, while The Mechanical Ballet 1979 stages seven kinetic sculptures on a platform, dancing beneath a linen sheet. Both are theatrical, spot-lit for inspection, while bodies remain unseen. Horn herself moved from making prosthetics in the 1980s to study the human quality of machines, celebrating their inbuilt weaknesses that, in her words, require them at times to rest, just like us. They do not always work, but rather than being frustrated with museum administrators when we encounter this, we should see it as intrinsic to the piece.

Rebecca Horn

Berlin Exercises Film ‘Touching the walls with both hands simultaneously’ 1974

Photo by Helmut Wietz

© Rebecca Horn 2016

In all of these examples, artists utilise technology to exceed and extend the body, showing humanity is too often inhuman. Machines are tools for making the future, and they help us to augment and exceed our own limits. The roots of the term prosthetic are in grammar: in the 1550s it referred to the addition of a letter or a syllable to a word, and only in the early 1700s did it come to be linked to the art of making artificial limbs. The body and language are the two things that we surely know best: whether linguistic or physical, prostheses are both material and metaphorical; they are markers of a technologised body, and far more than mere supplement. As Aimee Mullins, athlete, activist and protagonist in Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle 1994–2002, has eloquently explained: if a person needs false legs, why should they look like human ones? A prosthetic has the potential to extend the body far beyond the limits we are born into – a prospect that is equally terrifying and exciting.