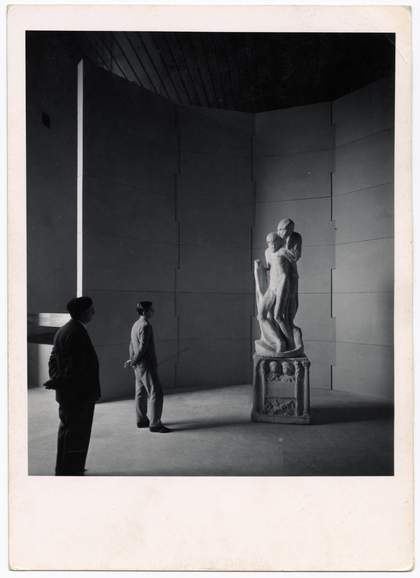

Photograph by Paolo Monti of Michelangelo's Rondanini Pietà 1564, installed at Castello Sforzesco in Milan, c.1956

© Civico Archivio Fotografico, Milano, photo: Paolo Monti, Fotogramma

What I remember most from my childhood and adolescence was a lack of colours. Everything was based on different shades of grey. Such was also the colour of my art education. Ninety-five per cent of reproductions in art books were in black and white, and of very poor quality. But as I didn’t have other options to compare them to, I had to love what I had.

I fell in love with a beautiful reproduction of Michelangelo’s Rondanini Pietà 1564 in a Russian book on the artist. The black and white figures of his group of four Slaves were my first contact with naked figures. Grey, marble naked bodies. And the figures of Daughter of Niobe and Aphrodite became the subject of my desire when I was 12. Without knowing about Pygmalion, I still treated these sculptures from the books as if they were alive.

Today I would say that this was the beginning of my sculptural education. Not only because of the lack of colour, but also because of the belief in the independent life of the form. Form was not just a form, but existed for something. There was a reason.

When I became an ‘international’ artist and could finally travel, I visited great museums and experienced the works of art of my Old Masters in the flesh. Probably the most unexpected moment of confronting the world of my imagination happened at Castello Sforzesco, which I visited to experience the masterpiece of my youth, Rondanini Pietà. When I entered the room I saw a nice, clean white sculpture. I didn’t feel any emotions. I was disappointed by the real work. Despite being three-dimensional, it seemed flat. My reaction was not due to the quality of his sculpture, but because of the strong image which I had carried in my mind’s eye for such a long time. The black and white reproduction had taken on the role of the real work of art. The same happened in Rome with Niobe.

As an artist I have always considered direct contact with a work of art and the space where the work is displayed to be the best way of experiencing it. But when I think about what happened with Niobe and Pietà, I’m not so sure.

Miroslaw Balka is an artist who lives and works in Otwock and Warsaw. He has a number of works in Tate's collection.