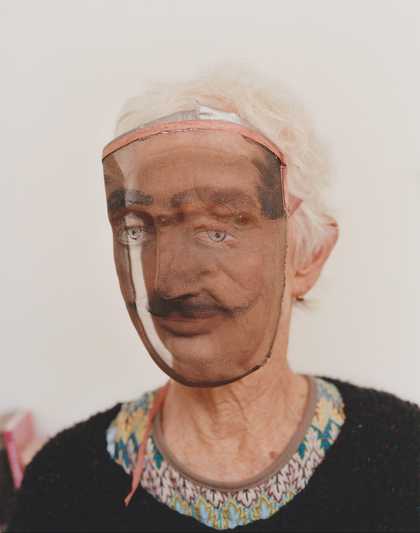

Stanley Spencer, Nude, Portrait of Patricia Preece 1935, oil paint on canvas, 76.2 x 50.8 cm (detail)

© The Estate of Stanley Spencer / Bridgeman Images, courtesy Ferens Art Gallery, Hull Museums, UK

I’m worried about my skin. I’m in a hotel in Virginia, I got married six weeks ago, and this is the first time I’ve been alone with my body in months. In the mirror, under tube lights, my thighs are pocked and striated with veins. I’m 40, on the downhill run. I used to scorn moisturiser but the horror show of ageing has caught up with me.

My Google search history from that afternoon: Myths and Facts about Cellulite, Cellulite: Top 10 Facts, Can you get rid of cellulite with exercise? Then I notice some bumps that didn’t used to be there. Why the Skin on Your Arms is Bumpy. Treating ‘Chicken Skin’ Bumps: Keratosis Pilaris. It’s the implacability of the body that frightens me – not just the ugliness of the manifestation, but the sense of invisible processes – malign or lethal – going on beneath the skin.

A long time ago, in the early 1990s, I worked as a life model. I was 17 when I started, mid-20s when I stopped. It paid ten pounds an hour – better than bar work. I borrowed a green silk dressing gown from my boyfriend’s mother, travelling from art school to sixth-form college to adult education centre by bus. I’d cross my legs and twist my torso in front of an electric heater. Once, in a class in a Portsmouth loft, I felt abruptly dizzy and came round to find an anxious crowd of pensioners clustered about my naked body.

When I prowled the easels in the break, what I saw was always the same: outline, skin bag, the more or less improbable architecture of the human form. Legs, fingers, nose. It was what my body looked like, sure, but not anything like how it felt to live inside it. There are two bodies, aren’t there? The one you see in magazines, the one that is available to strangers’ eyes, and the one you inhabit: the leaky vessel, permeable and expulsive, prone to rents and fractures; a conversion machine, a factory, slippery and bilious, its secret compartments stained rose madder and Chinese red.

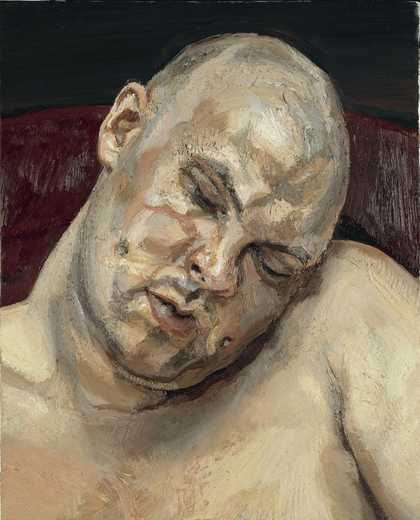

Stanley Spencer, Self-Portrait with Patricia Preece 1937, oil paint on canvas, 61 x 91.2 cm (detail)

© The Estate of Stanley Spencer / Bridgeman Images, photo © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

I feel like I’ve been searching for images of that other body all my life. The closest I’ve come:

- a photograph of a drawer swimming with body parts, by Joel-Peter Witkin, which I glimpsed in a magazine as a teenager.

- Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb 1522, body as transitional object, hands and feet livid, suffused with purple.

- Under the Skin, that slick, sleek, body-horror flick.

In it, Scarlett Johansson plays an alien fallen to earth, garbed in woman-skin, cruising the streets of Glasgow in her white transit, her cheap black wig. She chokes on cake, she can’t swallow. In bed with a man, she abruptly rears back, grabs a lamp and examines the aperture between her legs. Pussy shot as crisis, it reframes teen sexting as existential anxiety. Am I all there? Does this anatomy suit me?

The best bit – or maybe the worst, depending on your taste – was what happened to the men that Johansson’s alien collected. She walked with them into a black room, undressing as she went. The floor under her feet was solid, but the men sank into viscid liquid. Down they went, into the black pool. Submerged, they swelled and wrinkled, time’s advance accelerated. One bloated body burst, with a noise like a starter’s pistol, leaving a wrinkled skin suit in the water. A time-lapse nature documentary of what’s in store – the uneasiness, the insanity of setting up house in a transient vessel.

I had sex for the first time the same year I began working as a model. We were in a room in Southsea, listening to Pink Floyd – the record with the sleeve showing an ear photographed underwater. I took my earrings out, and then, feeling that this was a significant act, somehow sexual in its own right, I put them back in and took them out more slowly, where my lover could see me. It isn’t easy to inhabit the body, is what I’m trying to say; it isn’t easy to stop being a picture – pretty as, or trying to be.

It’s funny that sexiness is so associated with images of physical perfection. When we talk about the pornification of everyday life, part of what we mean is an impossible amplification of visual attainment – a two-gender world, each unambiguous sex honed and plucked and pumped and sheened. Bodies being penetrated or displayed, showered with effluent in extremis, but God forbid you see a bloodied Tampax string or zit.

Personally, I prefer the sex you get in a Bacon painting, where bodies turn into apes or dissolve into sand, into corpuscles, into red mist. It’s the edges I’m chasing, the point of exchange. Someone told me recently about looking up through a skylight in Italy, late at night, and seeing a group of wolverine writhing and tumbling over the glass. Maybe they were having sex, she said, or maybe they were fighting – anyway, it was disgusting. Yes, I said, but what I really meant is: I wish I’d seen it, the Muybridge transitions inside the wooden frame, like Bacon’s wrestling, copulating bodies in their invisible cages.

Stanley Spencer, Nude, Patricia Preece 1935, oil paint on canvas, 50.8 x 76.2 cm (detail)

© The Estate of Stanley Spencer / Bridgeman Images

This spring, I modelled for the first time in decades, for my friend Chantal. She used to paint pallid, angular girls in fashion poses, but over the years her brush has become more concerned with the actuality of flesh. Hulking white backs, flowery pants, the canvas as the mirror in which you apprehend the onset of ruin, the actuality of decline, the translation of skin into long, unsteady licks of flake white and chromium yellow.

I liked sitting. It all came back to me while walking barefoot over a floor thick with charcoal dust, washing my hands in the paint-stained sink. We ate cupcakes from the Hummingbird Bakery, and then I curled myself into a comma and let my face settle.

Chantal worked fast. We were done in two sessions. I wasn’t allowed to look until the end. My nose was like a banana, I looked anxious, my dress jarred with the red blanket. I think I’m in love with ugliness, Chantal said, and if my vanity was upset – for who doesn’t want to be an etiolated green plant, pliant and nubile, all legs and elbows and slanting eyes – I loved the way she articulated the smart of being there at all, an animal with its eyes open, not quite gelling with the room. There I was, the figurative thing, one continuous accident: a bag of old skin, tired, frightened, electrically alive.

*

All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life, curated by Elena Crippa, Curator, Modern British Art, with Laura Castagnini, Assistant Curator, Modern and Contemporary British Art, supported by Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members, is at Tate Britain, 28 February – 27 August.

Olivia Laing's latest book, The Lonely City, is published by Canongate. Her first novel, Crudo, is published by Picador in June 2018. She is currently working on Everybody, a book about bodies and freedom.