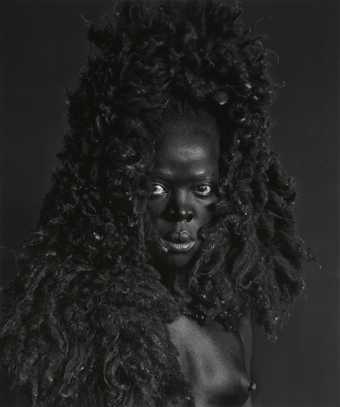

Zanele Muholi

Phila I, Parktown 2016

Gelatin silver print on paper

80 × 53.5 cm

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times. I think that is true of painters, sculptors, poets, musicians. As far as I’m concerned, it’s their choice, but I choose to reflect the times and situations in which I find myself. That, to me, is my duty. And at this crucial time in our lives, when everything is so desperate, when every day is a matter of survival, I don’t think you can help but be involved … How can you be an artist and not reflect the times? That to me is the definition of an artist.

— Nina Simone

It is our responsibility as activists and artists – as activists who practice art – to challenge all ‘isms’, starting with racism. To combat bias and erasure. To keep the dialogue going and create opportunities for others less fortunate or privileged. To open access to spaces historically denied to us – to black, queer, trans, female-bodied, and gender nonconforming individuals, especially. That is my main agenda going forward: to queer, to blacken, to open, and to occupy spaces.

— Zanele Muholi

On 14 June 2020, the sun shone brightly in Brooklyn. Heat rose above the heads of more than 15,000 people, all adorned in shades of white – a nod to the 1917 National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) silent march for Black Life. While energy palpably thrummed throughout the crowd, crisp coverings partially occluded the faces of those present, a symptom of political life in the midst of a pandemic. As the streams of people flooded the semi-circular concrete exterior framing the Brooklyn Museum of Art, a collective cry could be heard: ‘Black Trans Lives Matter’.

This rally marked an unprecedented moment in American political life: a monumental march calling attention to the astronomical rates of police violence against Black trans women and men. Importantly, its significance cannot be siloed. This radical moment of collectivity was rooted in an ethos of care preceded by decades of organising, with a transnational resonance that exceeded the scope of the march itself.

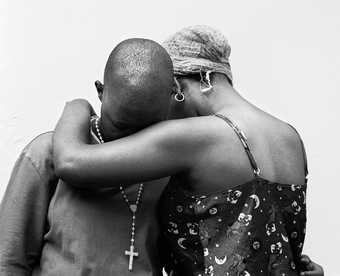

Zanele Muholi

ID crisis 2003

Gelatin silver print on paper

32.3 x 48.5 cm

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

This rally marked an unprecedented moment in American political life: a monumental march calling attention to the astronomical rates of police violence against Black trans women and men. Importantly, its significance cannot be siloed. This radical moment of collectivity was rooted in an ethos of care preceded by decades of organising, with a transnational resonance that exceeded the scope of the march itself.

To acknowledge that this collective action centred on the threshold of the Brooklyn Museum is to acknowledge the undeniable link between artistic expression and political struggle, especially with regards to LGBTQIA+ histories and experiences of Blackness.

Indeed, just five years prior, with the opening of the 2015 exhibition Isibonelo/Evidence, the institution housed the work of an artist whose career continually attests to the bond between the political and visual: Zanele Muholi.

Zanele Muholi

Comfort 2003

Gelatin silver print on paper

48.5 x 60 cm

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Muholi is a South African photographer who has dedicated their practice to grappling with the forces of systemic violence and epistemic silence that plague Black LGBTQIA+ communities. Sustaining a relentless work ethic and incisive vision, Muholi’s photographic practice is one of visual activism and archival assembly, making the museum space an especially rich terrain for their interventions. Working against normative narratives of history, they use each presentation to expose the divine graces and painful traumas that populate experiences of Black queer life in South Africa and beyond. Through their photographs, Muholi compels viewers to revel in the beauty, elegance and dignity of those within this community. In the process, they confront the community’s collective vulnerability to the violence of a South African state whose constitution purports to advance progressive political values, while its body politic propagates discourses of homosexuality and nonconforming gender identity as existentially threatening and un-African.

Born in Umlazi, Durban, Muholi was trained in photography at the Market Photo Workshop in Newtown, Johannesburg – a rich space of image-making and documentary training founded in 1989 by the late photographer David Goldblatt. In 2003, Muholi completed an advanced photography course at the workshop, and by September 2004, they mounted their first solo exhibition, entitled Visual Sexuality, at the esteemed Johannesburg Art Gallery. With this salvo, their work shook the nation – transgressing social expectations and rendering deeply intimate compositions of Black LGBTQIA+ life.

The pictures in their first series Only Half the Picture 2003–6 are poetic in register and attuned to bodily movement. They gently reveal a chest being bound in the light of the emerging morning; a hug of comfort between two friends – a head resting in the crook of a shoulder; lovers’ legs strewn in languid layers, composing a tableau of sumptuous limbs. Muholi states: ‘I have the choice to portray my community in a manner that will turn us once again into a commodity to be consumed by the outside world, or to create a body of meaning that is welcomed by us as a [queer] community. I choose the latter path.’

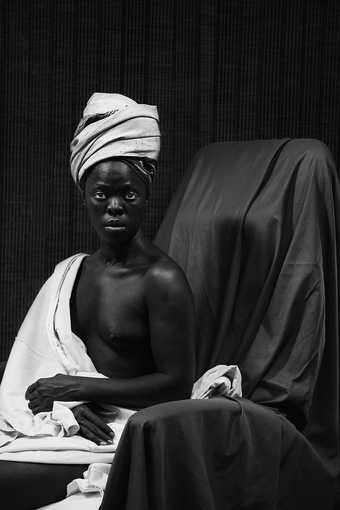

Zanele Muholi

Mini Mbatha, Glebelands Durban 2010

C-print on paper

76.5 x 50.5 cm

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Colour is fleeting in Muholi’s photographs, either serving to punctuate a series with the crimson red of menstrual blood, suffuse an interior kitchenette where a couple is locked in embrace, or mark the matching champagne tinted dresses of a wedding party. For them, it seems that colour generates a means of entering cherished spaces or queering public ones.

Zanele Muholi

Mpho Nefuri, Pretoria North, Gauteng 2018

Gelatin silver print on paper

76.5 x 50.5 cm

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

In contrast, monochrome persists throughout Muholi’s oeuvre, allied closely with the format of the portrait, and perhaps epitomising their acuity of vision with the expansive project initiated in 2006, Faces and Phases. A nuanced exploration of Black lesbian, trans and gender nonconforming subjectivity, Faces and Phases presents a carefully composed glimpse into a community often violently silenced and targeted. In each portrait, the subject faces the camera, with an open and direct gaze. Captured with extreme clarity, sharp details and fine tonal range, Muholi positions each figure centrally, initiating a silent, but loaded conversation between the subject and the viewer.

These images are assertions of existence. They are portraits as powerful testimonies to the realities of specific individuals who occupy particular spaces, who retain their names – faithfully noted in Muholi’s captions – who hold a gaze unflinchingly, and without fear. The picture plane becomes a space where humanity and agency cannot be intervened upon or consumed; where the subject is central within both visual and conceptual frames.

Zanele Muholi

Sibusiso, Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy 2015

Gelatin silver print on paper

80 x 56 cm

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

While Muholi’s Faces and Phases may seemingly evoke the strictures of the photographic typology, it refutes at every turn the notion of an itemised monolith, parsed to its constitutive parts. The series does not render objects, but rather human subjects – and even more than this, as Muholi qualifies: ‘these are not [just] subjects, these are my people, this describes the person I am.’

Pivoting from a collective portrait to an interior excavation, Muholi’s most recent body of work Somnyama Ngonyama (isiZulu for ‘Hail the Dark Lioness’), witnesses the artist engaging in an act of formal subversion: a series of self-portraits. In this project, Muholi pushes the bounds of what the genre of portrait- making might permit them – composing images that are transfixing in execution and stirring in conceptual significance. Expanding Muholi’s repertoire of resistance, these images directly confront visual and political histories of the Black body through allusions to specific figures in Muholi’s personal life and their larger cultural zeitgeist. These figures are referenced through Muholi’s captions and embodied visually by the artist. Festooned in accoutrements of quotidian life – a chair, plastic gloves, a scarf, a bowl – Muholi assembles themself in spare scenes, yet somehow evokes grandeur through gesture and varied expressive poses. The site of the self-portrait is an emotive one: simultaneously vulnerable and restorative.

Zanele Muholi

Miss Tee Menu, Parktown, Johannesburg 2014

Gelatin silver print on paper

76.5 x 51 cm

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

Yet the politics of space and visual histories of race persist in this imaginary. The series retains a number of images with the title MaID (‘My Identity’) or, put differently, ‘maid’, conjuring histories of labouring Black women in domestic servitude in South Africa, and globally – the Black body made a means of production and expendable commodity.

With this, Muholi’s use of black and white extends beyond classical photographic appeals to documentary truth or legitimacy, ultimately offering a meditation on Blackness as a consistent presence, an incontrovertible component of the self. Intellectual historian Hlonipha Mokoena has said: ‘Dark skin still troubles both blackness and whiteness because it refuses to be reduced to other things… In [their] multiple personas, Muholi embodies dark skinned women who provoke you to stare at them. It’s hard to look away; their gazes seduce you, despite yourself.’

Concretely, Somnyama Ngonyama emerges out of Muholi’s peripatetic lifestyle as an artist and activist. They created the series between Africa, North America and Europe – across Amsterdam, Charlottesville, Durban, Florence, Gaborone, Gothenburg, Johannesburg, London, Malmö, Mayotte, New York, Oslo, Philadelphia, Paris, Syracuse and Umbria. In a 2017 conversation with curator Renée Mussai, Muholi asserted:

As a series, [Somnyama Ngonyama] speaks about occupying public spaces to which we, as black communities, were previously denied access … Too often I find we are being insulted, mimicked and distorted by the privileged ‘other’. Too often we find ourselves in spaces where we cannot declare our entire being. We are here; we have our own voices; we have our own lives. We can’t rely on others to represent us adequately, or allow them to deny our existence. Hence, I am producing this photographic document to encourage individuals in my community to be brave enough to occupy spaces – brave enough to create without fear of being vilified, brave enough to take on that visual text, those visual narratives. To teach people about our history, to rethink what history is about, to reclaim it for ourselves – to encourage people to use artistic tools such as cameras as weapons to fight back.

Zanele Muholi

MaID, Delaware 2017

Gelatin silver print on paper

60 x 40 cm

© Zanele Muholi, courtesy the artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

With this polemic disposition, it is no wonder Muholi’s work has commanded consistent critical attention and garnered interest on a global scale. Balancing impeccable aesthetic execution with perceptive political awareness and social critique, Muholi is an artist whose work shifts the spaces it encounters, through images that are attuned to the complexities of Black South African LGBTQIA+ identities and sensitive to the granular nature of historical formations.

Deeply reflexive in their thinking, Muholi positions their work within a Black radical photographic tradition with references that extend as much to the albums of African-American portraits presented at the 1900 Paris Exposition (world’s fair in Paris) by W.E.B. Du Bois as they do towards Santu Mofokeng’s The Black Photo Album / Look at Me: 1890–1950, a 1997 archival project portraying Black South African photographic subjects at the turn of the century. Deeming the camera not as a luxury, but a necessity of visual activism – akin to Gordon Parks’s ‘choice of weapons’ – Muholi has built a repertoire of resistance that is insistent and collective. Their photographs offer fulsome accounts of expression and existence, to which future generations will undoubtedly refer.

Note: LGBTQIA+ is an acronym for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, queer (or questioning), intersex, asexual and other non-binary gender identities.

Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern, 5 November – 31 May 2021. Co-curated by Yasufumi Nakamori, Senior Curator, International Art (Photography) and Sarah Allen, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern with Kerryn Greenberg, Head of International Collection Exhibitions, Tate, formerly Curator, International Art, Tate Modern. Supported by the Zanele Muholi Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate Patrons and Tate Members. Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor. Organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, Gropius Bau, Berlin and Bildmuseet at Umeå University.

Oluremi C. Onabanjo is a curator and scholar of photography and the arts of Africa, currently completing a PhD in Art History at Columbia University, New York.