Michael Bird

After the war, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson were still influential figures in St Ives, but there was a whole new generation of younger artists: Peter Lanyon, Terry Frost, Bryan Wynter, Patrick Heron and, a bit later, Roger Hilton. Some had had terrible wartime experiences, and there was a feeling of intensity and urgency – of wanting to get on with things. I wonder whether, after half a century, as experience and memory turn into art history, we’re in danger of losing touch with the excitement, the unpredictability, the clash of personalities that went on there. Are we turning St Ives into something too serious, maybe even too dull?

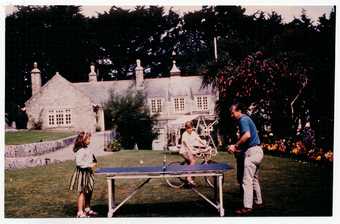

Peter Lanyon and daughter Anna Mary playing table tennis, with son Matthew on bicycle, at Little Park Owles, Carbis Bay c.1960

© Tate archive

Anthony Frost

Thinking of Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth reminds me of two stories. The first is that my father [Terry Frost] took over Ben’s studio. One thing he told me he regretted was that he found an old Ben Nicholson painting there, on hardboard, and he painted over it with white emulsion to use for one of his own works. I’m searching for that Ben Nicholson to this day.

Terry Frost (left) and Denis Mitchell (standing below) at St Ives Carnival mid-1950s

© Tate archive

Rose Hilton

Roger [Hilton] had a studio in Newlyn. Tom Barnes, the old harbourmaster, owned it, and when Roger left, he gave him a few paintings for the rent. Tom used them to repair the studio. They were ruined – but they were recognisable.

Andrew Lanyon

Recognisable, but ruined! I like that.

Rose Hilton

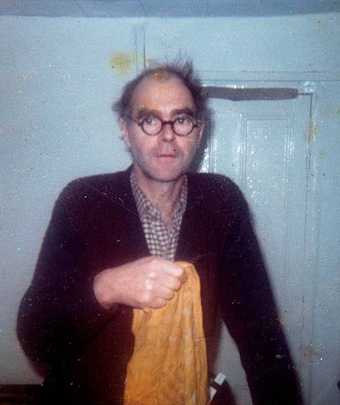

Roger Hilton, soon after moving into the cottage at Botallack 1965

© Courtesy Rose Hilton/Tate archive

Anthony Frost

The other story is about Barbara Hepworth. At the time Denis [Mitchell] and dad were her assistants. When journalists or photographers came round, she didn’t want them to see that she had these people working away on her sculptures. So she would shut the workers in the greenhouse, where they had their morning breaks. Then Barbara would start polishing the sculpture, as if she’d been at it all day. One time my father was bursting for a pee, but she wouldn’t let them out, and the only thing he could find was a pot with a geranium with very dry earth in it – but the pee went straight through and trickled across the greenhouse floor, and out under the door, between the legs of the visitors. Barbara banned him from having biscuits for the rest of the week.

Andrew Lanyon

Dicon Nance [potter and cabinetmaker] used to work for her. He told me about the little bell Barbara rang, which meant all her assistants were to remove themselves. It was quite a ritual. These are the kind of myths that people latch on to – if artists just had tea together and got on rather well, it wouldn’t make good copy.

Michael Bird

But there was quite a lot of falling out, wasn’t there?

Andrew Lanyon

Yeah, inevitably, over quite a lot of years.

Rose Hilton

When Nessie Graham was interviewed about [the poet] Sydney Graham after he died, the journalists rang me and said they were coming round to talk about his friendship with Roger. And Nessie called me up and said: ‘Just make out that they had afternoon tea, and not all that drinking.’ And I said: ‘Well, I can’t do it,’ so I couldn’t do the interview. It just was not like that. I don’t think Sydney ever had a cup of tea!

Anthony Frost

When I first moved back to Cornwall, I went round to see Sydney. There was a poem on the wall that I really liked, and I said to him: ‘What a fantastic poem’. And he just ripped it off the wall, threw it into the fireplace, poured paraffin over it and set light to it. I was shocked. Nessie said: ‘Don’t worry darling, he’s got another copy upstairs. He’s being a naughty boy.’

Michael Bird

Maybe such dramatics were all part of being able to get on with the work. Andrew, I think you said that sometimes with your father you felt that these conflicts generated adrenaline?

Andrew Lanyon

Denis Mitchell said it. He suspected that my dad fell out with people because it helped him to paint in an emotional state. It’s worth remembering that St Ives had every kind of personality. And the more personalities you’ve got, the easier it is for all the excitement to happen, which makes an art movement.

Michael Bird

And that was the case then, wasn’t it? There were a lot of very strong personalities?

Andrew Lanyon

Yeah, you had somebody who painted very emotionally, and you had other people, such as Ben Nicholson, who were much more analytical, like surgeons.

Rose Hilton

Sometimes when people came round to the house, or when I’d been out with Roger, and he’d been aggressive with someone, it was no good trying to get through to him then. In the morning I’d say: ‘You were really awful to that person.’ And he would say: ‘Good – no wonder I feel so great today.’ It must have been the adrenaline, or maybe just that they felt like individuals after having a row.

Andrew Lanyon

If you think about it, it was very considerate of them to keep their rows – these high and lows, the victories and emotional upsets – within their own circle. It might have included the odd poet…

Michael Bird

The poetry and the painting are often kept apart in people’s minds. But Sydney Graham was obviously closely involved with the artists. Words and ideas were important in the art community.

Rose Hilton

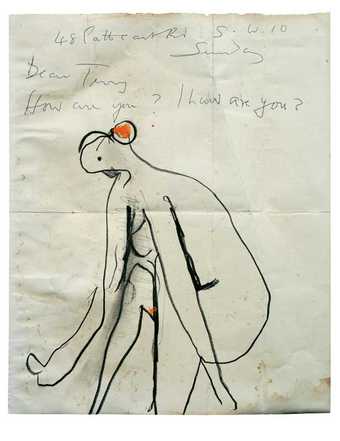

Sydney always illustrated his letters. He was always drawing. The page always looked good.

Illustrated letter by Roger Hilton sent to Terry Frost c.1959

© Photograph: Steve Tanner

Anthony Frost

I’ve recently been going through some of the archival materials at my parents’ house. There are boxes of correspondence with people such as Victor Pasmore, or Roger Hilton. My dad was writing about painting and the correspondents were writing back, writing all the time about painting.

Michael Bird

That’s interesting. From a distance people often think of St Ives in quite sensual terms the shapes of the landscape, the experience of the weather, the storminess and so on – but there was a strong intellectual strand, wasn’t there?

Andrew Lanyon

There was a high level of interchange of ideas. And, of course, there were those who came from abroad, such as Gabo and Rothko.When my father had visitors, it was out of bounds for us to go near the room. He was shut in, talking away – we’d be outside fighting. You used to have that intellectual interchange quite a lot, though probably not so much in the pub. He would go out in the evening to play dominoes with the locals. But the thing was, being a local himself, and mixing with intellectuals as well as locals, he felt he couldn’t really do anything that didn’t have integrity, because he’d be questioned all the time by people in the pub about the stuff he was doing. He felt that whatever you made, you had to make it bloody well. So he was essentially a craftsman first – he mixed his own paint and was careful about what he used.

Michael Bird

Your father didn’t have much time for that whole debate about whether art should be abstract or figurative?

Andrew Lanyon

Well, he got involved a lot in what went on in the Penwith Society [where Nicholson and Hepworth had supported the formal categorisation of members as either abstract or representational artists]. He was very cross, because he said he had been fighting in the war against Fascism, then he came back here and it was on his doorstep. While he was away, his position in St Ives had been usurped by the ‘king and queen’ – Ben and Barbara – and he was relegated to the status of ‘prince’. In fact, I discovered that he played the role of Goldilocks to the three bears – the three Bs, Ben, Barbara and Bernard [Leach]. When Bernard was away, he used to go into the pottery, roll out the clay with a rolling pin and make slab pots and decorate them rudely. So he was, in a sense, desecrating these sacred cows. And he did the same with Barbara and Ben.

Michael Bird

Do these pots still exist?

Andrew Lanyon

There are about a dozen of them. One is called the ‘burp pot’ – it looks as if it is burping. There is a sort of ‘benign ferocity’ about them, as one critic put it. If my dad hadn’t had these sacred cows, he wouldn’t have been able to use humour in his art as he did. It very much shaped him. And the Cornish like to attack everything that is slightly precious.

Michael Bird

The humour is important, isn’t it? You think of Hepworth and Nicholson’s very cool, elegant Modernism as something that takes itself extremely seriously. People look at St Ives art in a museum setting and that element of humour, of craziness, of satire, is often lost. But there are your father’s satirical collages…

Andrew Lanyon

They were always parting shots – and he often sent witty postcards at Christmas.

Rose Hilton

Yes, it was to the people whom he considered friends, including Roger – he would use these images that he had lying about, such as a photograph, and then send them a funny collage.

Andrew Lanyon

Roger and Sydney worked as a team against any kind of preciousness.

Rose Hilton

Oh, they did. If someone was being very pompous, they would prick the bubble.

Anthony Frost

It must have been a strange time. I can see this sort of bursting of the bubble. But they were also doing something important in the art world, and there would be critics coming down, who would be building it all up, in a sense. I remember one magazine did a fashion shoot with models posing in studios with the artists.

Michael Bird

Roger Mayne did some wonderful photographs of your father.

Anthony Frost

Roger lived with us for a time. It was ridiculous, all eight of us in a tiny house. When we went to bed he would be photographing, and when we woke up in the mornings he would be there, photographing – all the time.

Andrew Lanyon

I think this thing with writers is very good. We had two such fine voices with Arthur Caddick and Sydney Graham – deep resonant voices like two great wirelesses. The sound of poetry was important to them. We also had Patrick Heron – his are some of the best art criticisms of the twentieth century.

Michael Bird

There was a difference of opinion between Patrick Heron and your dad in the end?

Andrew Lanyon

That was about mining. There was a plan to open up a new mine near Zennor. My father was in favour of keeping the local community alive and going. He said that was better in the long term for the environment than fossilising the landscape.

Anthony Frost

How did they get on about painting?

Andrew Lanyon

Nobody ever wrote better than Patrick on my father’s early painting. He understood it.

Michael Bird

A lot of your father’s work connects with the industrial side of Cornwall, doesn’t it? The old mining area around St Just…

Andrew Lanyon

It was the same as Alfred Wallis seeing other people painting boats – they didn’t know what it felt like to be in a boat, they were just portraying what they saw. My dad saw them looking at the landscape and painting what was before their eyes. And he said: ‘No, there are men under there mining. I want to show what I know and what I feel, not just what I see.’

Anthony Frost

That’s interesting. My dad said that when he went drawing with your dad, Peter would make him lie down on the ground, and look up, and roll over.

Rose Hilton

So in that way it wasn’t totally intellectual, but involved the whole of the body?

Andrew Lanyon

It was about physical sensation and trying to get into paint so much more than just through the eyes. It was like shutting your eyes and attempting to paint. My father used to run up and try to catch a view by surprise, before you intellectualise it. In that fraction of a second when you look at a painting you’ve done which you haven’t seen for a while, you know if it’s any good.

Michael Bird

Was this having to experience things strongly another side of the hard-drinking culture, the experimentation with drugs?

Rose Hilton

I think they were using drugs such as mescaline as cures at that time. You could get it on prescription – it wasn’t difficult. So Bryan [Wynter] did get some, and he did experiment, and so did some of the other people, including Roger. This all happened up at the Carn [Wynter’s cottage].

Anthony Frost

I remember going up there. Bryan used to make home-made fireworks. So you’d go there for bonfire night. My dad said that once he got so drunk he fell over a wall and was unconscious. He woke up to find Doom [Wynter’s tame raven] on his chest saying ‘Terry, how are you?’ in Bryan’s voice. He got up and just ran!

Michael Bird

Andrew, I like what you wrote in one of your books about the word ‘creating’ being used for children being disruptive.

Andrew Lanyon

We were always being told off for ‘creating’. And as a child my father also might have been told off for creating.

Michael Bird

So the whole idea of creating was linked to mischief?

Andrew Lanyon

Absolutely. It is a very important element in his work, as somebody who said ‘Up the rebels!’ all the time, and was always looking for a different point of view or making mischief.

Anthony Frost

My dad always talked about going round to see Roger working on a painting. And Roger would say to him: ‘If you’re going to put a dot there [gestures], put it there. And if you’re going to put it there [pointing elsewhere], you’d better put it there.’ So Terry would say: ‘Where are you going to put it, Roger?’ And they would both say: ‘Let’s go to the pub.’ And as Roger was going out, he painted the dot behind him as he shut the door. They discovered where it was when they came back.

Rose Hilton

We used to go for walks, when the boys were small, and Roger would say: ‘Thank goodness I haven’t got to think about painting now.’ I always felt that he was a painter of moods in some way, because he used to get worked up and ratty [before painting].

Michael Bird

What brought him down to Cornwall to work? He had this high-level studio-based training – he wasn’t really a landscape artist…

Rose Hilton

Well, I only knew him in 1958, and he was already coming down then. Patrick was a neighbour in London, and invited him down. And then he met Sydney, and there was instant attraction on both sides.

Michael Bird

Was that a personal thing, or to do with the work?

Rose Hilton

I think sometimes people are immediately attracted to a type, even a physical type. Of course, the drinking was something they shared.

Anthony Frost

There was a cricket match – artists against farmers – every year. And the farmers would always make sure there was a long interval in the pub. It was one of their tactics. When they came out, the artists were all pissed.

Michael Bird

When you think of the London art scene at the time – the Soho pubs and that sort of thing – it was very much a man’s world. But in St Ives it seemed a bit more to do with families.

Anthony Frost

When I think about Walk Along the Quay, which turned out to be one of my dad’s biggest things and is growing in reputation now, well of course he walked along the quay, because he was pushing one of us in the pram, watching all those masts moving…

Rose Hilton

We can only guess what they were doing. We don’t really know what caused them to paint as they did, I feel.

Andrew Lanyon

One forgets that they did have an immense amount of fun.

Michael Bird

And quite risky fun sometimes.

Rose Hilton

Roger had a story about Peter. He was rushing down one of those narrow lanes in St Ives and Peter was chasing after him in the car.

Andrew Lanyon

He probably used a car like a brush. I think it was just to give him a scare for a laugh, because he was very in control of the machine. He had done quite a lot of racing. He wanted to be a racing driver, but he couldn’t – you’d have had to live in London and have lots of money.

Michael Bird

So there was quite a strong element of seeking thrills and sensations?

Andrew Lanyon

Speed is an important element in his art, and movement. However, that said, I think that narrative actually drove him more than the desire to make an image. Storytelling was phenomenal in St Ives, and the locals were quick-humoured people.

Michael Bird

When people focus on abstract art, that idea of narrative tends to get lost, doesn’t it?

Andrew Lanyon

It seemed very useful to my dad. He got through abstraction very quickly and it simply became another tool of many hung up on the wall. But I think that he wanted to tell stories. With abstraction, you can cram in a lot. For him, it was a system of telling quite a long story in the one image.

Rose Hilton

Whether it was to do with family or with being in Cornwall, Roger became more anthropomorphic in his work. He couldn’t resist using bits of the human body. He used that as a vehicle for his abstraction, more than the landscape even. He would paint the mood. I don’t mean just his mood – that’s what is so dynamic about his painting, and so alive. The viewer gets something different from it each time.

Andrew Lanyon

Someone said recently that Porthleven [by Peter Lanyon] looks like a council tip. And I don’t think it works. It’s all over the place. That kind of forthright comment is very good, because the trouble with St Ives now is that it doesn’t benefit from discussion in a way it did then. Television is an enormous wedge driven between people. In my parents’ day, you had much more of a sense of people meeting and discussing and talking.

Rose Hilton

From Roger’s point of view, it would have been better if he hadn’t come down to Cornwall. It was almost too tempting to go drinking if you were that way inclined. There were a lot of good times to be had if you were looking for them. He had much more of a routine in London – going to his studio every morning in St John’s Wood and then going for a drink in the evening. Whereas in St Ives, that routine disappeared. Sydney would come over and stay all day – and that was three times a week!

Michael Bird

Do you think that helped him to get a sort of wildness into the work?

Rose Hilton

Actually, he stopped oil painting for five years. Then it all came back when he was ill and couldn’t go out and about. He just did all these gouaches and drawings. He and Sydney fell out so badly that they didn’t see each other during Roger’s last three years – until just a few days before he died – which I suppose left him more free to paint.

Andrew Lanyon

With abstraction, you paint much more how you feel. If you are just sitting painting a still-life, there is a limit to how much you can put into it of yourself. Also, artists have the desire to communicate. That’s why you had these long sessions with Sydney and Roger. It was not just social, it was helping the work.

Michael Bird

If you want to understand the art, then the social side is crucial. It’s not just a string of stories that are a sort of background to the art.

Rose Hilton

I think that is a good point – social things fed the work. The artists were into each other personally.

Michael Bird

So, again, the very strong, very different personalities are important. You weren’t looking for someone who thought exactly the same way you did.

Anthony Frost

In my old man’s case, he wouldn’t have been the painter he became if he hadn’t come to St Ives. He met Adrian Heath in a PoW camp. Thank God, in a strange way, that he went there, as otherwise it would never have happened.

Michael Bird

And when you think where other people had come from – Roger was in the commandos, and he was also a prisoner.

Rose Hilton

For three years.

Michael Bird

And Peter Lanyon was with the RAF in the desert. There must have been a terrific desire to get on with something positive.

Anthony Frost

That was the thing – get married quick and get painting quick. Don’t piss around being a painter – do it.

Rose Hilton

It was almost a feeling that you’d been spared.