PABLO PICASSO

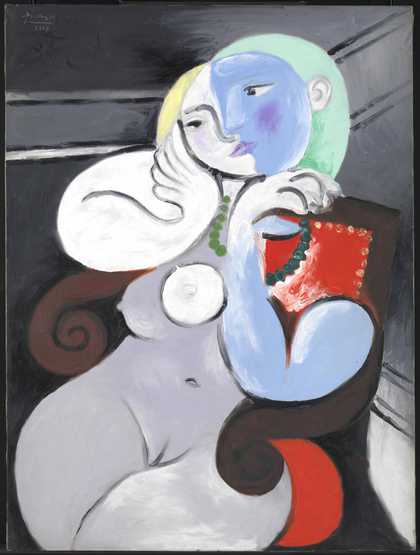

Pablo Picasso The Dream (Le Rêve) 1932, Private Collection © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2018

In 1932, Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) was not yet half-way through his career. After years of poverty as a young artist in Barcelona, he had moved to Paris at the turn of the twentieth century and, by the early 1930s, was both celebrated and wealthy. He was aware, however, that he was losing contact with his artistic contemporaries, and that critics were questioning his ability to create radical new work.

Picasso was always restless, constantly trying his hand at new things. His Blue and Rose periods in the early 1900s were mainly of figurative paintings. On discovering archaic and notwestern art, he moved further from naturalistic representation and radically reinterpreted it when he and Georges Braque invented cubism. Between the two world wars he made works inspired by classical art, and others that engaged with the contemporary interest in surrealism.

As a foreigner living in France, Picasso refrained from political activities and kept a distance from official engagements, including those with his native Spain. Things changed dramatically when Nazi German and Fascist Italian warplanes bombed the Basque town of Guernica in 1937, in response to which Picasso created a monumental black-and-white painting which to this day is regarded by many as the greatest anti-war statement in art.

Throughout his life, Picasso sought to revive the tradition of western art, especially painting. He competed creatively with his contemporaries, particularly Matisse, but also earlier artists including Velázquez, Ingres and Manet. He returned repeatedly to subjects such as the female nude, classical mythology – particularly the character of the Minotaur – and the bullfight.

Picasso married twice and had several other long-term relationships. He had four children. By 1932, his marriage to Olga Khokhlova was under increasing strain. The escape offered by his relationship with the significantly younger Marie-Thérèse Walter became a key inspiration for much of

his work from this period.

The work that one does is a way of keeping a diary.

Pablo Picasso

LOVE FAME TRAGEDY

1932 was a make-or-break year for Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). In October 1931 he had turned fifty. He was inundated with invitations to exhibit his work. At the same time, critics openly discussed whether he was an artist of the past rather than the future. Picasso’s grand apartment on the rue La Boétie, his tailored suits and chauffeur-driven car symbolised his rise from poor Spanish migrant to international superstar, as did his marriage to the Russian ballerina Olga Khokhlova, his principal model and inspiration for much of the late 1910s and early 1920s.

But Picasso felt increasingly restless and critically sidelined. He bought an eighteenth-century mansion in the Normandy countryside where he experimented with sculpture. He created a chaotic studio in a Parisian apartment identical to the one below in which he lived a life of bourgeois respectability with his wife and son. He was in a secretive relationship with a younger woman, Marie-Thérèse Walter. He flirted with surrealism while trying to beat Henri Matisse at his colourful game.

These contradictions were brought into focus by his first major retrospective in June 1932. In the preceding months Picasso channelled his energies into ambitious paintings intended to silence his detractors. As the year progressed, the mood darkened from sensuous exuberance to ominous anxiety. Rarely overtly political, Picasso’s work nonetheless reflected the times: a world – including his native Spain – increasingly in the grip of economic depression, mass unemployment, populist nationalism and the rise of totalitarian regimes. If 1932 began for Picasso under the sign

of love, it ended with a premonition of tragedies to come.

ROOM ONE

Christmas Day 1931, 23 rue La Boétie: having spent the festivities with family and friends, Picasso completed a small painting he had worked on for a week. Woman with Dagger is a surrealist nightmare of a woman killing her sexual rival. The same day, he also painted a large canvas of a seated woman, her facial features replaced with a heart. While the former alluded to increasingly strained marital relations, the latter was a painterly dream about Picasso’s secret lover, 22-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter.

Just as Olga Picasso and Marie-Thérèse Walter demarcated the poles of Picasso’s personal life, so his work explored the tensions between painting and sculpture, surrealist distortion and sensual colour harmonies. This complex force field gave rise to some of Picasso’s most accomplished works. It was his

urge to renew and reinvent himself which turned 1932 into Picasso’s ‘year of wonders’.

ROOM 2: JANUARY AND FEBRUARY

On 26 February 1932, Picasso’s La Coiffure (1905) sold in Paris for a record-breaking 56,000 Francs. Aside from raising hopes that the worst of the economic crisis might be over, this price was indicative of the high regard in which Picasso’s early work was held. Moments such as this strengthened Picasso’s resolve to prove his continued relevance.

Throughout January, with his impending retrospective in mind, Picasso produced in his Paris studio a series of ambitious portrait paintings. All of them depict a female figure seated in an armchair, reading, sleeping or apparently absorbed in music. The sitter is almost certainly Marie-Thérèse Walter. The model, though, is imagined rather than real as Picasso was not in the habit of painting from life.

Despite their shared subject matter, the paintings differ greatly in style and mood. Saturated colour harmonies alternate with surrealist distortion; at times the figure is shown in sensual abandon, at others it veers towards caricature or dissolves altogether into a sculptural arrangement of abstracted shapes. Seen together, these paintings testify as much to Picasso’s restless inventiveness as to his complex relationship with the women in his life. The still life from early February marked a momentary break from the female figure as the dominant subject of Picasso’s work in 1932.

ROOM 3: BOISGELOUP

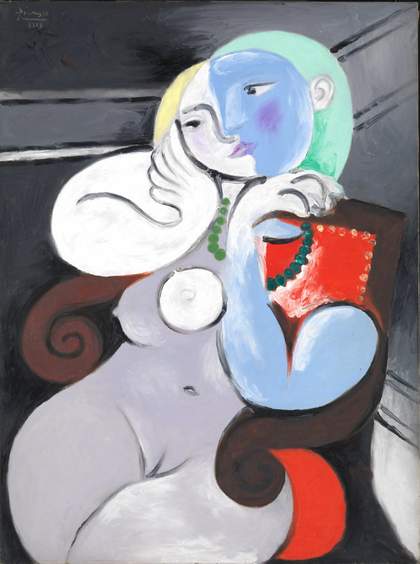

Pablo Picasso Nude in a Black Armchair (Nu au fauteuil noir) 1932 Private Collection, USA. Photo Courtesy of Richard Gray Gallery © Succession Picasso/DACS 2018

In June 1930, Picasso had purchased an eighteenth-century château in Normandy. Boisgeloup provided a welcome retreat from city and public life, and was an easy drive from Paris in the chauffeur-driven Hispano-Suiza limousine the artist now owned. Despite its basic plumbing and heating, in the spring and summer months the mansion became a gathering place for family and friends. When neither was present, it served as a secret meeting place for Picasso and Marie-Thérèse Walter.

A room on the second floor of the corner tower, offering sweeping views across the village of Gisors, became Picasso’s painting studio. He turned one of the stables into a sculpture studio. Throughout 1931 he developed a new sculptural language, transforming Walter’s strong features into solid volumes and bulbous shapes.

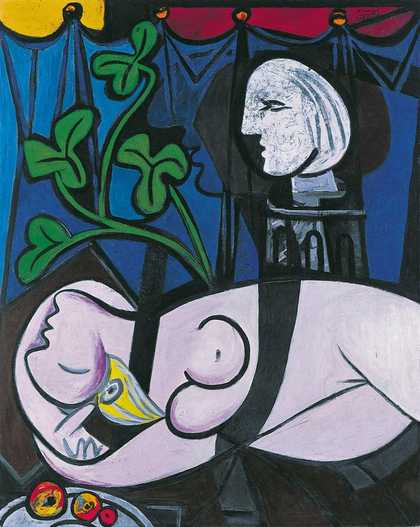

The Boisgeloup sculptures were published for the first time in a series of photographs by French-Hungarian photographer, Brassaï, taken at the end of 1932. They were also a key reference for Picasso’s painting in the first half of the year.

ROOM 4: EARLY MARCH

Early March marked a moment of extraordinary creativity, even by Picasso’s standards. Over the course of twelve days, he painted a group of large canvases which are exceptionally rich in colour and composition.

In one of the earliest, a bust in profile, suggesting both the Boisgeloup sculptures and Marie-Thérèse Walter, looks out beyond a still life. In the painting dated 8 March, the sculpture gazes at a philodendron plant and a reclining nude. In subsequent works, the nude takes centre stage, sleeping with her head in her arms.

While being a great formal innovator, Picasso privileged traditional subjects rooted in the history of Western painting such as portraits, still lifes and reclining nudes, a popular subject from the Renaissance onwards. Girl Before a Mirror echoes a similar painting by the French nineteenth-century artist, Edouard Manet, who was the subject of a major exhibition in Paris in 1932 which coincided with Picasso’s own. Like his friend and rival, Henri Matisse, Picasso sought continually to prove that figurative painting could be modern by injecting it with a new sensuality inspired by Walter.

ROOM 5: LATE MARCH TO MAY

If Picasso’s paintings in early March were major public statements, those later that month explored the darker realms of the unconscious. Painted across the Easter period, during a prolonged visit to Boisgeloup, they show abstracted female bodies, their orifices accentuated by the sun or the moon above. Paul Rosenberg, Picasso’s dealer since 1918, declined to show the paintings, commenting wryly: ‘No, I refuse to have any arse-holes in my gallery.’

The large horizontal nudes from April reveal Picasso’s renewed engagement with surrealism. Depending upon the viewer’s point-of-view, the figures can turn from nude to octopus holding a skull, and back again. One source of inspiration may have been an early documentary by the French filmmaker Jean Painlevé, revered by cinema enthusiasts like Picasso; another was Japanese erotica, known as ‘shunga’, by, among others, the nineteenth-century painter and printmaker, Hokusai.

As Picasso’s retrospective approached, his focus on painting increasingly gave way to the practicalities of organising this ambitious show. Woman in a Yellow Armchair is one of the last large figure paintings made in anticipation of the exhibition at the Galeries Georges Petit in June.

ROOM 6: FAME

Pablo Picasso Nude Woman in a Red Armchair (Femme nue dans un fauteuil rouge) 1932 Tate © Succession Picasso/DACS 2018

Retrospectives of living artists were unusual in the early 1930s. Henri Matisse’s exhibition at the Galeries Georges Petit, Paris, in 1931 had been a rare exception. To facilitate his own retrospective there in June 1932, Picasso had declined offers from The Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Venice Biennale. Unlike Matisse – and to avoid the latter’s mistake of giving too much power to his dealers – Picasso took full control of his show. When asked how he would curate his retrospective, Picasso replied provocatively: ‘badly’. Resisting attempts to provide a chronology of his artistic development, Picasso chose instead to mix up works from different periods in a dense hang, and did not provide dates of individual works. Those of 1932 were interspersed throughout as if to indicate that all his output was equally contemporary. The frequent appearance of Marie-Thérèse Walter’s features in his recent work provided the first public clue that a new woman had entered the artist’s life. Yet pride of place in the retrospective was given to a group of paintings that celebrated Picasso’s family, with portraits of his wife and son presided over by a self-portrait from his Blue period in the early 1900s.

While fashionable Paris gathered at the opening, the only person missing was Picasso himself: he went to the cinema instead. If dealers had hoped Picasso’s exhibition would stimulate an art market hard-hit by the Great Depression, they were disappointed. Many of the collectors who attended the glamorous opening soon lost their fortunes to the economic and political turmoil engulfing the world. Picasso’s retrospective turned out to be the last major exhibition held at the Galeries Georges Petit, which closed in 1933.

ROOM 7: JULY AND AUGUST

As soon as his retrospective opened, Picasso bulk-bought canvases and retreated to Boisgeloup for the summer. Freed from the weight of critical expectation, his painting style became faster and more fluid, with smaller works exploring new themes.

Picasso’s Reclining Nudes of late June and July picked up where he had left off before the retrospective. Transformation, with one thing turning into another, remained central to his imagination. With their extremities turned into pointy flippers, the small nudes suggest the similarities between women and sea creatures, perhaps inspired by Marie-Thérèse Walter’s prowess as a swimmer. (Though he had grown up by the sea, and though he planned to install a swimming pool at Boisgeloup, Picasso could not swim.)

Nude Woman in a Red Armchair is one of the few large-scale paintings of the summer. Here Picasso returned to his preferred subject matter of early 1932, without preparatory drawing and with his paint and line flowing more sensually than ever, and the woman, unusually for this subject, being naked. An X-ray of the painting reveals that it was almost certainly executed in a single fast-paced session.

ROOM 8: BLACK ON WHITE

Throughout 1932, Picasso produced a number of charcoal drawings on canvas. Though most would not appear in the catalogue raisonné being compiled by Zervos, they are not studies, but finished works in their own right. They often relate to paintings on similar themes albeit with a focus on line and form rather than colour. Rubbings, erasures and over-drawing make visible the process of image construction.

Drawing was central to Picasso’s imagination. As much is demonstrated by his complex line drawings as well as his sketchbooks. Here he often elaborated on a particular theme, such as the artist in his studio, by making a series of drawings in quick succession. These drawings were conceptual exercises rather than preparatory studies and rarely translated into paintings.

Picasso’s sketchbooks show the same disdain for chronology as did his retrospective exhibition. On 25 January 1932, for example, he dated the first page of sketchbook number 40 as Paris, 25 January 1932, but then abandoned it until the last weeks of the year. Similarly in April 1932 he picked up another sketchbook, number 17, which he had begun in January 1930.

ROOM 9: SEPTEMBER AND OCTOBER

Pablo Picasso Nude, Green Leaves and Bust (Femme nue, feuille et buste) 1932 Private Collection © Succession Picasso/DACS 2018

As summer drew to a close, Picasso’s work filled with beach scenes. Yet the artist himself, apart from a brief family excursion to the seaside in Normandy, spent most of the summer with family and friends in Boisgeloup. Marie-Thérèse Walter holidayed separately in the south of France.

In early September Picasso left for Zurich to visit what was his first major museum exhibition. On his return he began work on an extraordinary series of drawings on the subject of the Crucifixion. In particular, he was inspired by Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Despite suggestions that he had gone to see the painting on his way back from Zurich, it is unlikely that he actually did so. Arcadian scenes of reclining nudes and flute players interspersed his darker representations of Christ’s suffering.

Picasso continued to engage with classical themes, both secular and religious. And, if Matisse had been his sparring partner in the first part of the year, he now competed with surrealism. He was sceptical of group membership of any kind and disliked the theoretical framing of art, preferring instead to trust intuition and process. Yet he was happy for his work to be reproduced and discussed at length by the surrealist poet and provocateur André Breton, in the first issue of the magazine Minotaure.

ROOM 10: NOVEMBER AND DECEMBER

Towards the end of the year, Picasso turned to a new and darker subject matter: the threat of drowning, and the possibility of rescue. The impetus may have been Marie-Thérèse Walter who, while swimming in the sewagecontaminated river Marne, contracted a serious viral infection. Some biographers have argued that, since the childhood death of his younger sister from diphtheria, Picasso felt doomed to cause women to suffer. This is suggested by some of the works on paper in which fatal accident is transformed into sexual violence.

In the final paintings of the year, colour detaches from line or is reduced to shades of grey. The proliferation of works on paper, especially prints in multiple stages to which he turned in the latter months of the year, indicates Picasso’s pleasure in experiment. The different subjects and rapidly changing styles suggest a growing restlessness. The carefully constructed balance which had made 1932 Picasso’s ‘year of wonders’ was coming to an end.

Essentially, there is only love. Whatever it may be.

Pablo Picasso

In 1935, Marie-Thérèse Walter became pregnant by Picasso. The birth of their daughter Maya marked the end of his marriage to Olga Picasso. Though they never divorced, she moved immediately to the south of France, taking their son with her. Picasso described this as the worst period of his life.

The political and economic situation in Europe also deteriorated. Hitler was appointed German Chancellor in January 1933, Mussolini had consolidated a fascist dictatorship in Italy, and Spain became engulfed in civil war which ended with the defeat in 1939 of the Republican cause with which Picasso sympathised. Six months later, the world was once again at war.

The Rescue, painted in the first days of 1933, foreshadows the agony of the mother and child in Picasso’s emblematic antiwar painting, Guernica (1937). By then, Picasso’s world as it had been in 1932 was lost forever.