Albert Rutherston Laundry Girls 1906

Albert Rutherston,

Laundry Girls

1906

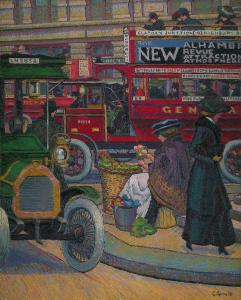

The two female subjects of this painting, one seated and one kneeling, are depicted marking laundry with thread before it is sent out to be professionally cleaned. Rutherston uses sharply contrasting outlines to describe the shadows and highlights of draped fabric, including the plain skirts and features of the women. His early work treated scenes of domestic life, although he was later known for his whimsical illustrations and theatre design.

Albert Rutherston 1881–1953

Laundry Girls

1906

Oil paint on canvas

915 x 1170 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Albert R. 06.’ in black oil paint bottom left

Presented by Humbert Wolfe 1939

N04996

1906

Oil paint on canvas

915 x 1170 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘Albert R. 06.’ in black oil paint bottom left

Presented by Humbert Wolfe 1939

N04996

Ownership history

Sold at the New English Art Club, London, July 1906; ... ; John Spiegelberg by 1925 when listed by R.M.Y. Gleadowe, until at least 1932 when listed by Rutherston in letter to Tate Gallery; ... ; Humbert Wolfe by 1939, by whom presented to Tate Gallery.

Exhibition history

1906

Thirty-Sixth Exhibition of Modern Pictures by the New English Art Club, Dering Yard Galleries, London, June–July 1906 (62, as ‘The Linen Markers’).

1934

Paintings and Drawings by Albert Rutherston, Leicester Galleries, London, January 1934 (71).

1935

Eighty-Sixth Exhibition of the New English Art Club (50th Anniversary of the Constitution of the Club), Suffolk Street Galleries, London, October–November 1935 (83).

1975

Edwardian Reflections, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, July–October 1975 (138).

1987–8

The Edwardian Era, Barbican Art Gallery, London, October 1987–February 1988 (not in catalogue).

References

1925

R.M.Y. Gleadowe, Albert Rutherston, London 1925, p.15, reproduced pl.5.

1933

Stanley Casson, Artists at Work, London 1933, reproduced between pp.84–5.

1939

The World of Art Illustrated, 3 May 1939, reproduced p.23.

1943

Albert Rutherston, ‘From Orpen and Gore to the Camden Town Group’, Burlington Magazine, vol.83, no.485, August 1943, p.202, reproduced pl.II C.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.2, London 1964, pp.581–2.

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, pp.126–7, reproduced pl.14.

1988

Max Rutherston, Albert Rutherston, London 1988, pp.5, 15.

1996

Albert Rutherston, exhibition catalogue, Sally Hunter Fine Art, London 1996, [p.3].

Technique and condition

Rutherston chose a plain-weave linen canvas for this painting. He originally purchased the canvas pre-stretched from the artists’ colourmen Roberson, whose stamp marks the back of the cloth. The canvas was supplied sized and primed with two layers of lead white, probably in an oil medium. There is no visible evidence of any initial drawing beneath the paint film, although it is difficult to discern beneath the build-up of paint.

Rutherston initially appears to have laid in the main compositional elements, possibly with the addition of linear contouring in various tones of warm brown/orange-coloured paint. There is visible evidence of this monochrome painting beneath the baskets, the women’s clothing and the dark green skirting board but it is not possible to discern whether it covers the entire face of the canvas. The artist worked over this monochrome painting applying opaque paint, with much white admixture, in a simple build-up of layers. The paint is well bound in oil medium and probably had considerable gloss when first applied.

The artist used bold, sharply contrasting outlines, in particular to describe the shadows and highlights of folded and draped material to help create the illusion of stiff fabric. Contours rather than varying tones are also used to delineate features. The figures’ flesh, some of their clothing and the basket are somewhat softer in gradation, the artist probably sweetening the paint (see Tate N03847).

Rutherston made some changes to the composition during painting by overpainting earlier work with opaque paint, which is visible as raised brushwork at the surface, for example, the skirt of the figure on the left was reduced in length and width, originally covering much of her foot. He also modified colour and in places different coloured paint is visible beneath overlaying layers, where the paint is more thickly built up and wide drying cracks have formed.

After painting, the artist decided to reduce the size of the canvas and had another colourmen, Percy Young, remove it from its original stretcher and re-stretch the painted canvas onto a smaller stretcher. The painting was reduced in width and part of the right side of the painted surface was folded and stapled onto the turnover edge, it was then varnished, probably with a natural resin varnish.

Natasha Walker

November 2006

How to cite

Natasha Walker, 'Technique and Condition', November 2006, in Nicola Moorby, ‘Laundry Girls 1906 by Albert Rutherston’, catalogue entry, November 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Background

Albert Rutherston never became a member of the Camden Town Group, but his friendship with some of the main protagonists and his early involvement with the Fitzroy Street circle make him a noteworthy figure in the history of the group’s development. During his lifetime, he was best known as an illustrator and theatre designer. In a published discussion on painting in 1933, Stanley Casson labelled Rutherston’s characteristic illustrations as ‘thoroughly decadent young creatures with pale blue skins and curly legs prancing about among trees that never existed in landscapes that seem to shake like mirages’.1 Rutherston agreed with this colourful description of his work but rejoined that he had once been ‘a painter of solemn and serious pictures, who painted costermongers, laundry girls, seamstresses, and the like – and very glad I am that I did’.2

Laundry Girls is one of these earlier oil paintings which took as their subject working class women engaged in domestic labour, and it was through such works that Rutherston appeared to align himself for a time with the subject matter of Walter Sickert and other members of the Fitzroy Street Group. The series also included Laundry Girl (whereabouts unknown), exhibited at the New English Art Club in 1907, of which the critic in the Observer wrote, ‘The “Laundry Girl” by Mr A Rothenstein concentrates within one little frame every conceivable kind of ugliness’,3 and Standing Laundress 1909 (private collection),4 which was one of Rutherston’s last paintings in this vein. In 1910 a significant shift occurred in Rutherston’s work and he abandoned his ‘solemn’ method of painting in favour of the imaginative style described by Casson and evident in Tate’s Paddling (Tate N04569).

Laundry Girls depicts two young women in an interior, one seated on a stool and one kneeling on the floor, with a basket full of what looks like tablecloths between them. There are other fabrics such as curtains and a fringed cloth hanging on a drying line, with a wooden screen-fold clothes horse behind them, and another basket of laundry sitting in the left-hand corner of the picture. The girls are dressed in plain and functional skirts and blouses with neckcloths, and the figure on the right also wears an apron. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the laundry of a middle class household would either have been done at home, usually carried out by domestic servants or a laundress hired to come in for the day,5 or it would have been sent out to a commercial laundry or a local washerwoman, usually a working class woman trying to earn some money from home.6 It is not clear from Rutherston’s painting whether the two girls are meant to be domestic servants engaged in doing the laundry for a private household, or laundresses hired from outside to deal with the washing. A reviewer in the Aberdeen Free Press described the work as ‘a brilliant though rather ugly picture of young Jewesses in a laundry’,7 although there is no further information to corroborate this supposition which was perhaps based on no more evidence than the artist’s name.8 The painting was first exhibited at the New English Art Club under the title The Linen Markers, which suggests that the girls are engaged in marking items from the household’s washing with needle and cotton thread so it can be sent to an outside professional laundry. A small mark sewn onto each item would have distinguished the washing from others and ensured its return to the correct house.

Laundry

The process of washing clothes and household linen in the twentieth century, prior to the general adoption of washing machines and chemical detergents during the 1950s, was an extremely labour intensive and complicated activity which would take up at least an entire day each week. Essential laundry skills were taught to girls who attended school, and numerous contemporary manuals were produced for instruction in the best methods for successful cleaning, such as The Art and Practice of Laundry Work for Students and Teachers by Margaret Cuthbert Rankin, published in 1905. Monday was usually reserved for doing the laundry since it left the rest of the week for drying, ironing and airing, but the washing ritual began on Sunday when the dirty items were collected, sorted according to their uses and extent of soiling, and soaked to loosen the grime and stains.9 Laundry day itself began early with the heating of water and the cleaning of the wooden tubs and other equipment to prevent any dirt from transferring to the fabrics during the washing process.10 The soaked items were then scrubbed in a tub with soap, soda or borax, rinsed, boiled, rinsed again and white linens were further steeped in bluewater (a kind of weak dye) to counteract yellowing and improve the odour.11 Heavy stains were treated with paraffin and some linens, such as tablecloths, were starched to make them stiff.12 The washing was then put through a wringing machine and, weather permitting, was placed outside to dry or, alternatively, was hung inside on drying racks and rails.13 Some items were also put through a mangle to give the material a smooth, glossy surface.14 Finally the clothes were ironed, folded and put away, usually just in time for the entire process to be started over again.15

In choosing laundry girls as a subject worthy of an oil painting, Rutherston was following an established modern trend of representing the realistic experience of everyday life. Laundry work was traditionally carried out by women as part of their duties within the domestic sphere, but in the nineteenth century it also became a way that working class women could earn money outside of the home. Public laundries employed women to do the washing and ironing, although the wages were poor and the working conditions were notoriously unpleasant. At the same time, the figure of the laundress or washer-woman began to emerge as a popular character in contemporary literature. The laundress was traditionally depicted either as an archetypal working class woman, struggling through hard work to overcome the poverty of her situation, or, alternatively, as a young, flirtatious, sexually available girl. This was particularly true in nineteenth-century French literature with works such as Contes Drolatiques (1832) by Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850). Rutherston was certainly familiar with the work of Balzac, which he read during the summer of 1899 while on holiday in Vattetot, Normandy with his brother, William, and William’s new wife, Alice Knewstub.16 Perhaps the most famous laundress in literature is the heroine of L’Assommoir (1877) by Emile Zola (1840–1902), which tells the story of Gervaise, a working class mother who starts her own laundry. Although she initially makes a success of it, her husband squanders all of her earnings in the Assommoir, the local drinking shop, and she is brought down into poverty and squalor. The novel is a closely observed account of the terrible social conditions of the working classes in France and also documents the odious nature of laundry work:

The sorting took a good half-hour. Gervaise made piles all round her, throwing all the men’s shirts together, and all the women’s chemises, then the handkerchiefs, the socks, the cloths. When she picked up something belonging to a new customer she’d mark it with a cross in red thread, so she’d recognise it again. In the warm air a stale stench rose up as the dirty laundry was turned over and over ... She was used to filth, and didn’t find it in the least disgusting; she plunged her bare pink arms right in among shirts yellow with dirt, cloths stiff with grease from washing-up water and socks eaten away and rotted by sweat. But, amid the penetrating fumes that hit her in the face as she bent over the piles, a kind of languor came over her. Sitting doubled up on the edge of a stool and leaning towards the floor, she was stretching out her hands to the left and the right more and more slowly and smiling vaguely; her eyes dreamy, as if this human stench was making her drunk. And it seemed as though that was where her laziness first began, that it came from the stifling reek of dirty clothes poisoning the air around her.17

Laundresses were also a familiar subject in pictorial imagery of the French nineteenth century. As the writer Eunice Lipton has pointed out, they were a regular theme for Salon painters during the second half of the century, although these paintings were generally nostalgic and picturesque images of domestic contentment which rarely conveyed the drudgery involved.18 Conversely, in popular imagery the occupation of the laundress was suggested to be a thinly veiled façade for prostitution and sexual immorality.19 The famous impressionist painter, Edgar Degas, extended and challenged these perceptions in his series of paintings of washerwomen and women ironing, made between about 1869 and 1902, in which he captured the physical effort and tedium of laundry work through the unrefined and realistic poses of women at work. In Laundresses (Les Repasseuses) c.1884–6 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris),20 Degas painted a woman ironing a shirt so that the difficulty of using a heated flat iron is evident through the considerable pressure she exerts with her arms. Her companion stretches and yawns while taking a break from the perpetual and back-breaking toil. Degas deliberately avoided popular conventions suggesting overt sexual availability or domestic contentment. His laundresses occupy an ambiguous position, simultaneously conveying independence, exploitation and an unattractive coarseness tempered by an earthy sexuality.

Subject and inspiration

Rutherston’s Laundry Girls combines an objective, closely observed realism with a subjective middle class vision and sense of class distance. The faces of the models are not conventionally beautiful and the artist has focused on realistic aspects of their appearance, for example he has recorded the reddened appearance and prominent veins of their hands which reflect their familiarity with hard manual labour. However, unlike Degas’s laundresses who have been captured in awkward but realistic poses, Rutherston’s women have been deliberately posed to provoke sympathy in the viewer. The poses of the two models are graceful and submissive, particularly that of the kneeling girl on the right which evokes a praying Madonna. Despite the evident drabness of their circumstances, dress and surroundings, Rutherston has invested the women with conventional charm and appeal. He has employed heavy chiaroscuro, smoothly painted surfaces, with a focus on form and outline, particularly in the treatment of their clothes, which imbues the scene with a sense of serious authenticity and traditional artistic gravitas. A number of critics reviewing the New English Art Club exhibition in 1906 noted the severe simplicity of the work. The Speaker wrote that Rutherston ‘delineates his figures so clearly as to make them appear a little hard in outline, but his colour is invariably cool and sweet, and he has a strong instinct for well-balanced design’, while the Jewish Chronicle stated that ‘“Linen Markers”, although a trifle harsh in outline, is an effective piece of realism without being oppressive’.21

Despite the painting’s appearance of authenticity, there are a number of signs which indicate that Rutherston staged the picture in his studio using an array of props to create the scene. There is no sense of the energetic activity of real work. The placing of the fringed cloth on the drying line, the curtains hanging on the clothes horse and the material draped over the side of the wicker basket in the left-hand corner provide visual interest and structural balance to the painting, but are too deliberately arranged to record an actual observation of a laundry. Items hung up to dry would have been hung as straight and as neatly as possible to facilitate ironing. Neither does the painting depict any real sense that the job of the laundry girl is unpleasant or arduous. It is a sanitised and one-sided view of the experience, which presents the women as working contentedly and therefore in a way that was unproblematic for the middle class viewer. Far from being an accurate record of working class labour, Rutherston’s painting reveals his own position as a middle class man who did not do his own laundry.

It would be wrong to assume, however, that Rutherston’s painting was intended to be either a snapshot of a real situation or a social document. Although Laundry Girls draws an inevitable modern comparison with similar subjects by Degas, the tradition upon which Rutherston was building at this time was not French impressionism, or even Sickert’s early evocations of contemporary London life (he also painted a picture titled The Laundry Girl c.1906),22 but the linear, academic figure-painting characteristic of Slade School teaching and frequently seen in exhibitions of the New English Art Club. The sense of design and clarity of Rutherston’s composition are clearly based on detailed drawings of the two figures from life. Rutherston’s choice of subject matter is certainly part of a wider contemporary trend towards an interest in modern life, but the manner in which he interprets the theme draws upon a stylistic tradition familiar to him through his Slade education and the work of figurative artists such as Alphonse Legros (1837–1911). Perhaps the most useful comparison to Laundry Girls is a series of paintings by Rutherston’s close friend and peer, William Orpen (1878–1931), featuring Lottie, a washerwoman who lived in Paradise Walk, Chelsea. Orpen not only used Lottie as a model for characters in his history paintings, he also depicted her within her natural working environment. Works such as Lottie of Paradise Walk 1905 (National Gallery of Canada) and Resting 1905 (Ulster Museum)23 mirror Rutherston’s detailed depiction of the clothes and tools of the laundress. However, the principal artistic intention remains the aesthetic arrangement and observation of a figure within an interior and therefore lies closer to portraiture than to historicism or social realism.

Unlike Lottie, the girls who modelled for Laundry Girls were not authentic laundry women. A description of Rutherston painting from a working class model in his studio in 1903 is provided by the poet and writer Humbert Wolfe in his autobiography, Portraits by Inference:

Albert had two rooms [at 18 Fitzroy Street] – a living and (it seemed from its general appearance) a dying room. For in the second everything was dead – the lay figure, three empty boxes of Gold Flake cigarettes, the brown broken teapot, and the pictures upside down or with their faces to the wall. But again, how wrong to make that pun, because the second was in fact not merely dead but doubly alive. For here creation was in progress. Here Lina the flower-girl from Piccadilly Circus, duly chaperoned by her mother in a black beaded cape – had patiently endured her immortality. With her black straw hat, slightly tilted, and clutching her shawl with the air of one clutching the last straw, she had watched Albert convert her from a girl into a legend. It frightened her.24

Like ‘Lina the flower girl from Piccadilly’, the ‘laundry girls’ were actually coster-girls, sellers of flowers or fruit and vegetable from a stall in one of London’s markets (see also Piccadilly Circus by Charles Ginner, Tate T03096). In an article for the Burlington Magazine in 1943 Rutherston wrote:

I was fortunate at that moment in having several Coster girls as models for a series of paintings I was at work upon – The Laundry Girls (Tate Gallery) was one, and Emily, the younger of the two who sat for this, blonde, amusing and pert, found great favour in the eyes of Sickert, who delighted to draw and paint her. 25

A drawing of Emily by Rutherston was reproduced in the same article. In a letter to his nephew, John Rothenstein, Rutherston pointed out that she was also the model for a pencil drawing in Tate’s collection The Straw Hat c.1911 (Tate N05309), formerly identified as the work of Harold Gilman but now attributed to a follower of Sickert.26

Coster-girls were a favourite subject for many of the artists of the Fitzroy Street and Camden Town groups and they appear in paintings by Sickert, Gore, Ginner and Gilman, portrayed as representatives of working class urban women. Despite the grind of their everyday lives, costermongers were renowned for their colourful and flamboyant dress sense, described by Sickert as the ‘sumptuous poverty of their class’,27 which evolved into the traditional costumes of London’s Pearly Kings and Queens. Contemporary images of coster-girls emphasised their shabby glamour and combined an awareness of the struggle of their daily existence with a sense of cheerful resilience. Rutherston was an original contributor to the ‘Saturday Afternoon At Homes’ from 1907 at 19 Fitzroy Street and his admiration for the work of Sickert dated back to his student years at the Slade. However, his paintings of working class women, such as The Song of the Shirt 1902 (fig.1), pre-date his close association with Sickert and Fitzroy Street and reveal a closer affinity with the careful, precise paintings of his brother, William Rothenstein, for example Coster Girls 1894 (Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield).28

Albert Rutherston 1881–1953

The Song of the Shirt 1902

Oil paint on canvas

760 x 785 mm

Bradford Art Gallery

Courtesy of the artist's grandchildren

Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia

Fig.1

Albert Rutherston

The Song of the Shirt 1902

Bradford Art Gallery

Courtesy of the artist's grandchildren

Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Australia

Ownership

Laundry Girls was given to the Tate Gallery in February 1939 by the poet and writer Humbert Wolfe (1885–1940). Like Rutherston, Wolfe had grown up in Bradford in Yorkshire and the two were lifelong friends from the time of their schooldays at Bradford Grammar School, although Wolfe was three years Rutherston’s junior. Rutherston regularly visited his friend while Wolfe was studying at Oxford and in 1908, when Wolfe moved to London to work for the Civil Service, he briefly lived in Rutherston’s spare room at 18 Fitzroy Street. Through the artist, Wolfe met a number of important cultural figures in London and socialised with a group loosely associated with the New English Art Club.29 Wolfe began publishing poetry in the 1920s and Rutherston provided illustrations for Cursory Rhymes, a collection of his friend’s verse published in 1927. Lively descriptions of Rutherston at various stages of his life appear in Wolfe’s series of autobiographies: Now a Stranger (1933), which documents Wolfe’s childhood aged 7–9, The Upward Anguish (1938), which covers his university education and early life in London aged 17–22, and Portraits by Inference (1934), an account of his work and acquaintances in London.

It is not known how or when Laundry Girls came to be in Wolfe’s possession but he cannot have owned it for many years. The picture was first sold during its exhibition at the New English Art Club in 1906,30 although it is not known whether the buyer on this occasion was John Spiegelberg, the owner of the painting until at least 1932.31 In a letter to the Tate Gallery in February 1939, Wolfe wrote:

I have in my possession a painting by Albert Rutherston entitled, “Laundry Girls”. It is a comparatively large oil, and I think represents the very best of his art. I have felt for a long time that he has not been adequately represented in your great national collection, and I hope, therefore, that the Trustees would see their way to repair what appears to me to be an omission by accepting this picture as a gift.32

Wolfe’s gesture in offering Laundry Girls to the Tate Gallery is testament to his enduring friendship and respect for Rutherston, described in The Upward Anguish as ‘a lifelong affection dating from his fourth birthday’.33

Nicola Moorby

November 2003

Notes

Judith Flanders, The Victorian House: Domestic Life from Childbirth to Deathbed, London 2003, p.118.

Elizabeth Roberts, A Woman’s Place: An Oral History of Working-Class Women 1890–1940, Oxford and New York 1984, p.140.

Margaret Cuthbert Rankin, The Art and Practice of Laundry Work for Students and Teachers, London 1905, p.29.

N.E. Mann, Instructions in Elementary Laundry Work for Use in Schools and Technical Classes, Liverpool 1904.

Eunice Lipton, Looking into Degas: Uneasy Images of Women and Modern Life, Berkeley, Los Angeles and London 1986, p.122.

Albert Rutherston, ‘From Orpen and Gore to the Camden Town Group’, Burlington Magazine, vol.83, no.485, August 1943, p.202.

Reproduced in William Rothenstein Memorial Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1950, pl.3.

Philip Bagguley, Harlequin in Whitehall: A Life of Humbert Wolfe, Poet & Civil Servant 1885–1940, London 1997, pp.85–6.

Related biographies

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Albert Rutherston, ‘From Orpen and Gore to the Camden Town Group’ The Burlington Magazine, vol.83, no.485, August 1943, pp.201–5.

How to cite

Nicola Moorby, ‘Laundry Girls 1906 by Albert Rutherston’, catalogue entry, November 2003, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www