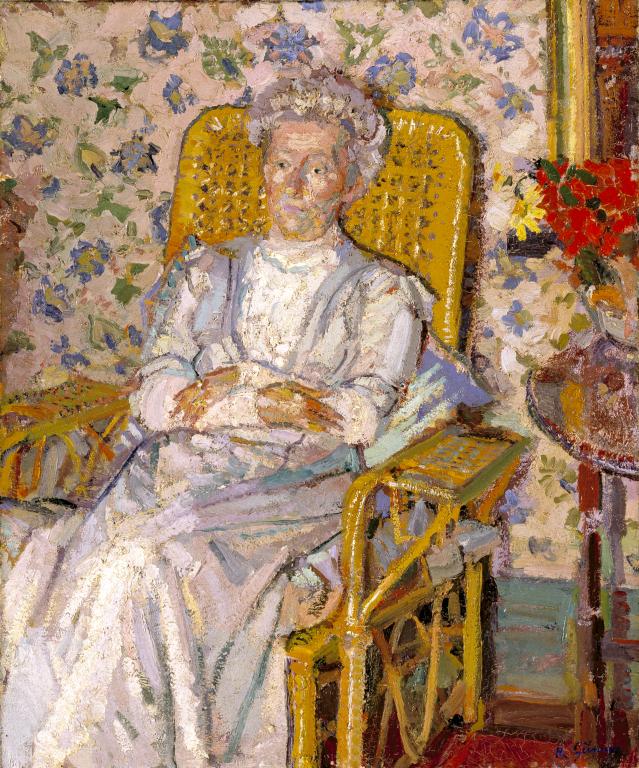

Harold Gilman The Artist's Mother c.1913

Harold Gilman,

The Artist's Mother

c.1913

Reclining in a wicker chair in the family drawing room at Snargate Rectory is Gilman’s mother, a recurring sitter for the artist who invariably painted the people and interiors around him. Painted in bright whites, the simplicity of her dress delineates her figure from the decorative floral wallpaper behind.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

The Artist’s Mother

c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 505 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1943

N05555

c.1913

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 505 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1943

N05555

Ownership history

Mrs Sylvia Gilman, the artist’s widow, from whom bought for £250 by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest and presented to Tate Gallery 1943.

Exhibition history

1912

?The Fifth London Salon of the Allied Artists’ Association, Royal Albert Hall, London, July 1912 (as ‘Thou shalt not put a Blue Line around Thy Mother’).

1913–14

Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others, Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, December 1913–January 1914 (43).

1914

Exhibition of Paintings by Harold Gilman and Charles Ginner, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1914 (47, reproduced).

1915

Works by Members of the Cumberland Market Group, Goupil Gallery, London, April–May 1915 (20).

1919

Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, Leicester Galleries, London, October 1919 (19 or 25, both as ‘The Artist’s Mother’).

1934

Paintings by Harold Gilman 1876–1919, Arthur Tooth & Sons, London, September–October 1934 (22).

1943

Paintings and Drawings by Harold Gilman (1876–1919), Lefevre Gallery, London, September 1943 (24, reproduced).

1944

The One Hundred and Seventy-Sixth Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, Royal Academy, London, April–August 1944 (59).

1944–5

A Selection from the Tate Gallery’s Wartime Acquisitions (Second Exhibition), (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts tour), Manchester City Art Gallery, November–December 1944, Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery, January 1944–February 1945, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, March 1945, Central Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, April 1945, Wakefield Art Gallery, May–June 1945, Castle Museum, Norwich, July–August 1945, Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, September–October 1945, Worthing Museum and Art Gallery, October–November 1945 (24).

1946–7

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (British Council tour), Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, January–February 1946, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 1946, Raadhushallen, Copenhagen, April–May 1946, Musée du Jeu de Paume, Paris, June–July 1946 (12), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Berne, August 1946, Akademie der Bildenen Künste, Vienna, September 1946, Narodni Galerie, Prague, October–November 1946, Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw, November–December 1946, Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1947 (11).

1947

Tate Gallery 1897–1947: Pictures from the Tate Gallery Foundation and Exhibition of Subsequent British Painting, Tate Gallery, London, May–September 1947 (5555).

1947–8

Modern British Pictures from the Tate Gallery, (Arts Council tour), Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, September–October 1947, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, October–November 1947, Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery, November–December 1947, Bristol City Art Gallery, January–February 1948, Russell-Cotes Art Gallery, Bournemouth, February–March 1948, Brighton Art Gallery and Museum, March–April 1948, Plymouth Art Gallery, April–May 1948, Castle Museum, Nottingham, May–June 1948, Huddersfield Museum and Art Gallery, June–July 1948, Aberdeen Art Gallery, July–August 1948, Salford Art Gallery and Museum, August–September 1948 (5).

1949

Exhibition of the Chantrey Collection, Royal Academy, London, January–March 1949 (292).

1969

Harold Gilman 1876–1919: An English Post-Impressionist, The Minories, Colchester, March 1969, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, April–May 1969, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, May–June 1969 (24, reproduced).

1973

Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, June 1973 (loan).

1989–92

Government Art Collection, September 1989–July 1992 (long loan).

1992–4

Government Art Collection, October 1992–December 1994 (long loan).

References

1949

Wyndham Lewis, ‘The Chantrey Collection at the Academy’, Listener, vol.41, no.1042, 13 January 1949, p.65.

1952

John Rothenstein, Modern English Painters: Sickert to Smith, London 1952, p.154.

1964

Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, vol.1, London 1964, p.236.

2000

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.169.

Technique and condition

The Artist’s Mother is painted in artists’ oil paint on primed stretched canvas. The support is one piece of plain, closely woven linen with a selvedge on the right-hand vertical length. The canvas does not appear to have been sized, allowing the primer to pass through the weave interstices to the back. The priming extends to the cut edges on three sides and stops just short of the selvedge. It comprises of a single opaque layer of white primer. The canvas is attached to a five-member stretcher with steel tacks. There is evidence along the bottom edge that the painting was re-stretched at some time. The canvas and its preparation are common to that found on all of Gilman’s paintings in the Tate collection (see also Tate T00096).

If there is any initial drawing, it and the early stages of painting are obscured by the density of later applications of paint. There are randomly positioned pin holes in all four corners but it is unclear as to what they relate. The painting has clearly been worked over a period of time. There is a remarkable accumulation of paint in some areas, such as around the sitter’s head and left-hand shoulder. In addition, the artist appears to have rubbed down areas of paint before continuing painting, for example, in the table on the right-hand side. By contrast, there are passages in which the paint film has been more freely worked and realised in a single campaign. The pattern of the wallpaper, for example, shows little correction and small areas of priming are left visible. Gilman seems to place deliberate emphasis on the manipulation of the paint with individual brushstrokes and drawn lines left clearly visible in the surface. His vigorous handling and less formulated approach seems to move away from earlier more restrictive working practices. At this time both Gilman and Spencer Gore had become interested in the emotional character of the subject, through their experience of post-impressionist painting. Gore said, ‘if the emotional significance which lies in things can be expressed in painting the way to it must lie through the outward character of the object painted’.1

While Gilman’s palette appears broadly consistent with that identified in other works of the period (see Tate N03684), he has also integrated medium-rich paints traditionally used for glazing; for example, natural madder lake has been used for the red of the flowers on the table, and in touches on the sitter’s lips and ears. The tonal contrast of the colours is reduced by an uneven coating of varnish, which has accumulated in the texture of the paint and has yellowed. Small fragments of crumbled priming and paint are embedded in the varnish. These were probably picked up when the varnish was brushed on after the paint had dried and hardened, suggesting that it was applied sometime after painting.

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan

June 2006

Notes

How to cite

Roy Perry and Sarah Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', June 2006, in Robert Upstone, ‘The Artist’s Mother c.1913 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Gilman painted several pictures of his mother Emily, née Purcell Gulliver. These include The Old Lady 1911 (Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery),1 The Artist’s Mother at Lacon Hall c.1911 (Aberdeen Art Gallery), Interior with the Artist’s Mother 1917–18 (fig.1) and The Artist’s Mother Sleeping c.1918 (private collection),2 as well as a number of drawings (fig.2). The Tate picture shows Emily Gilman in the drawing room at Snargate Rectory. The dabbed touch and heightened palette are common to other portraits of Gilman’s mother from this period, notably The Old Lady.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Interior with the Artist's Mother 1917–18

Oil paint on canvas

512 x 614 mm

Manchester City Galleries

Photo © Manchester City Galleries

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

Interior with the Artist's Mother 1917–18

Manchester City Galleries

Photo © Manchester City Galleries

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Portrait of the Artist's Mother writing in Bed c.1917

Reed pen and grey ink over indications in red chalk

289 x 229 mm

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Fig.2

Harold Gilman

Portrait of the Artist's Mother writing in Bed c.1917

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Photo © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

In his introduction to the memorial exhibition of Gilman’s work held in 1919, Charles Ginner drew particular attention to Gilman’s pictures of his mother, and specifically to the Tate painting:

In his first use of the purer impressionist palette, Gilman worked at the juxtaposition of separate colour tones in the manner of the French Impressionists. The portrait of his mother, seated in a wicker chair, full face, with her arms crossed on her lap, simple and dignified in composition and feeling, is perhaps the finest picture of this period. He painted several portraits of his mother, and his admiration and veneration for her were expressed by the dignity discernible in these works.3

James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1834–1903

Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, Portrait of the Artist's Mother 1871

Oil paint on canvas

1443 x 1630 mm

Musee d'Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.3

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1, Portrait of the Artist's Mother 1871

Musee d'Orsay, Paris

Photo © Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Further evidence that Gilman used such works to engage in a form of aesthetic didacticism comes from the art critic Frank Rutter, who recalled:

The prevailing fashion some years ago of putting a heavy outline round the contours of figures and other objects annoyed him [Gilman] exceedingly. The line did not exist in nature, colours melted one into another, and to put a line between them was untrue, therefore to be condemned. To signalise his abhorrence of this practice, Gilman once exhibited a portrait of his mother at the Allied Artists [Association] with the title, Thou shalt not put a Blue Line round thy Mother. Notwithstanding his seriousness, he had a keen sense of humour, and could enjoy a joke as well as anyone.4

It is unknown which of the paintings of his mother Rutter was writing about, but the careful placing of colours next to each other in The Artist’s Mother must make it a possibility that it was the work shown as Thou shalt not put a Blue Line around Thy Mother.5

Gilman’s pictures of his mother might also be viewed as studies of age. This is an attribute also found in his paintings of Mrs Mounter (see Tate N05317), which similarly have the character of a woman who is old, but still resilient and independent.

The wicker armchair in which Mrs Gilman sits is the one in which she is depicted by her son in several of the other portraits, and a photograph exists of her sitting in it.6 The wallpaper in the background appears to be the same as in Edwardian Interior (Tate T00096), another Snargate picture painted some years before, and establishing the location as the Rectory’s drawing room. Gilman frequently favoured placing his sitters against such decorative wallpaper backgrounds, which were often brightly coloured and with geometric patterns. The wallpaper in the sitting room at 47 Maple Street W1, glimpsed as a patterned strip at the centre of Mrs Mounter at the Breakfast Table (Tate N05317), appears to have been a particular favourite, and one which featured in several portraits. At the small art school he opened with Ginner in January 1916 at 15–16 Little Pulteney Street in Soho, Gilman would reputedly seat models in front of a screen covered with a boldly patterned wallpaper.7

Robert Upstone

May 2009

Notes

Charles Ginner, ‘Harold Gilman: An Appreciation’, in Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1919, pp.5–6.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Charles Ginner, ‘Harold Gilman: An Appreciation’ in Memorial Exhibition of Works by the Late Harold Gilman, exhibition catalogue, Ernest Brown & Phillips, The Leicester Galleries, London, October 1919, pp.3–8.

- Spencer Gore, ‘Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh &c., at the Grafton Galleries’ The Art News, 15 December 1910, pp.19–20.

How to cite

Robert Upstone, ‘The Artist’s Mother c.1913 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, May 2009, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www